Texte par / by Michel Ragon et copyright Albin Michel 2008

Translation and introduction by Paul Ben-Itzak

Si on a décidé de partager aujourd’hui cette extrait de la “Dictionnaire de l’Anarchie” de Michel Ragon (Copyright Editions Albin Michel, Paris, 2008), ce n’est pas car en aucun sens on adhère ni aux idées anti-Etatiste ou, surtout, les méthodes ou tactiques violentes de Nestor Makhno (ceci dit sans aucun constate sur ses idées et pratiques; on n’est pas experte au sujet de Nestor Makhno) — ni l’un ni l’autre est le cas. C’est plutôt car dans son histoire, comme raconté par feu Michel Ragon — qui a aussi écrit sur Nestor Makhno dans son roman historique “La Mémoire des vaincus” — surtout son face à face avec (à la fois!) l’armée Blanche et l’armée Rouge de Trotski — il y’a en a de quoi inspirer une nouvelle génération des Ukrainiens et qui, encore une fois, sont en train de lutter pour leur propre existence face a un surpuissant pouvoir Russe. Et car le fait même qu’il s’est battu pour l’Independence d’Ukraine il y déjà plus de 100 ans de ca contrarié le mensonge de Vladimir Putin que l’Ukraine été une invention des Bolchevicks; au contraire! — Paul Ben-Itzak

Makhno, Nestor

Fils de paysans ukrainiens misêrables, il est d’abord apprenti dans une fonderie, puis aide d’un marchand de vins. Dès 1906, il prend contact avec un groupe d’anarchistes-communistes paysans à Goulaiaïa-Polié. L’année suivante, à dix-huit ans, il commence une vie de clandestinité terroriste. Arrêtê, torturé, il est condamné à mort en 1910, peine commuée en travaux forcés à perpétuité. Transféré à la célèbre prison Boutirky, à Moscou, il y rencontre Archinov, qui lui fera découvrir la littérature illégale introduite frauduleusement. C’est en prison que Makhno fera son éducation politique. Il retient de Bakounine : «La passion de la destruction est une passion créatrice.»

En 1917, la révolution le libéré après six années de réclusion. De retour en Ukraine, il récuse le mouvement autonomiste. Contrairement aux accusations bolchevistes, qui considéraient la paysannerie comme incurablement réactionnaire et petite-bourgeoise, Makhno ne croit qu’en l’insurrection des paysans attachés à leur commune et à un mouvement révolutionnaire autonome de la paysannerie.

À peine revenu de prison, il fonde l’Association paysanne de Goulaiaïa-Polié, préconise l’abolition de l’État et de tous les partis politiques. Il exproprie les grandes propriétés terriennes, chasse les patrons de leurs usines et fonde des communes agricoles.

Son pouvoir est très vite contesté par Petrograd, hostile au séparatisme ukrainien. Archinov, qui est venu le rejoindre, lui conseille de rendre visite à Kropotkine, revenu en Russie. Mais celui-ci ne lui fixe aucun programme. Il décide alors de discuter avec Lénine, qui le reçoit au Kremlin pendant une heure et cherche à le dissuader de suivre la voie libertaire. «Les anarchistes, lui dit-il, sont pleins d’abnégation, ils sont prêts à tous les sacrifices, mais, fanatiques et aveugles, ils ignorent le présent pour ne penser qu’au lointain avenir […]. Je vous considère, camarade, comme un homme ayant le sens des réalités et des nécessités de notre époque. S’il y avait en Russie ne fût-ce qu’un tiers d’anarchistes tels que vous, nous, communistes, serions prêts à marcher avec eux.» Makhno proteste : «Vos bolcheviks n’existent pour ainsi dire pas dans nos campagnes. Presque toutes les communes ou associations paysannes en Ukraine ont été formées à l’instigation des anarchistes-communistes.»

Au printemps 1918, Makhno déclenche la révolte paysanne d’Ukraine. Il attaque les postes militaires des occupants allemands et austro-hongrois, les grandes propriétés agricoles, les fermes des koulaks. Ses cavaliers créent la surprise par leur rapidité, dans la tradition des cosaques.

En octobre 1918, Goulaiaïa-Polié est libéré. Les officiers autrichiens faits prisonniers sont exécutés, les soldats épargnés se joignent aux troupes de Makhno, mais, le 6 février 1919, l’Armée rouge entre à Kiev. Makhno, avec ses drapeaux noirs, se retire dans le sud.

À l’automne 1918, le journal activiste “Nabat” (Le Tocsin), considérant que la révolution en Ukraine peut rapidement devenir anarchiste, établit ses centres à Odessa. Archinov, Aaron Baron, et Voline, éminents théoriciens anarchistes, rejoignent Makhno en se chargeant de la propagande et de l’éducation. Toute fois, et quelle que fût l’amitié que lui portèrent Voline et Archinov jusqu’à la fin de sa vie, dans l’exil, Makhno éprouvera toujours de la méfiance, voire de la jalousie, pour les intellectuels anarchistes.

Au printemps 1919, celui que les paysans insurgées appellent “Batko” (Petit Père) a réuni une troupe de vingt mille combattants. Mais l’armée insurgée d’Ukraine doit combattre à la fois les troupes tsaristes de Denikine et l’Armée rouge de Trotski. Devant le danger que représente Denikine, Trotski signe un pacte d’action militaire commune entre son armée et celle de Makhno.

Le courage inouï de Makhno, qui se charge de toutes les actions dangereuses, a été souligné par tous les historiens. «Il semblait, écrira plus tard Archinov, que cet homme de petite stature fût bâti d’éléments particulièrement tenaces. Il ne reculait jamais devant aucun obstacle […]. Son calme tenait du prodige. Il ne faisait aucune attention ni aux milliers de projectiles qui décimaient les troupes des insurgées, ni au danger imminent d’être écrasé à chaque instant par les lourdes armées rouges.» Sa technique : la vitesse et la surprise. L’infanterie sur chariot suit la cavalerie.

Après la victoire commune des troupes bolcheviques et anarchistes contre l’armée blanche anéantie, Vorochilov ordonne à Makhno de porter désormais son offensive contre la Pologne. Makhno comprendre la piège, qui consiste à faire sortir les insurgées ukrainiens de leur repaire. Il refuse. Il n’a d’ailleurs pas d’ordre à recevoir d’un général bolchevique.

En janvier 1920, le parti communiste déclare Makhno et ses partisans hors-de-loi. Suivront huit mois de batailles acharnées entre rouges et noirs. Le 25 novembre, Trotski invite les principaux chefs makhnovistes à une réunion de conciliation en Crimée. C’est un piège. Tous sont arrêtés et fusillés, et la cavalerie de Crimée est anéantie.

Ordre est donné a toutes les unités de la Makhnovtchina d’intégrer l’Armée rouge. Makhno se retrouve avec deux cents cavaliers à Goulaiaïa-Polié. Il évite l’encerclement de l’Armée rouge et, pendant huit mois, traqué, dans l’hiver rigoureux, abandonne peu à peu son artillerie, ses chariots et ses réserves de vivres. Grièvement blessé, il est transporté par ses troupes dans une carriole. Le 13 avril, avec les cent cavaliers qui ont survécu, il passe le Dniester et se refuge en Bessarabie.

Dans l’exile, la vie de Makhno sera désormais celle d’un vaincu, d’un malade, affaibli par nombre des blessures. Au printemps de 1922, il s’échappe de Roumanie et entre en Pologne. Le gouvernement soviétique, qui a condamné a mort Makhno par contumace, demande son extradition. Les organisations anarchistes internationales lui obtiennent un visa pour Berlin, où il retrouve Voline. En 1924, Voline, qui a émigré en France, y prépare le transfert de Makhno.

Les anarchistes françaises l’accueillent avec enthousiasme. Mais tout le monde est surpris par sa déchéance physique. Parmi les réfugiés russes dans la capitale, Makhno est par ailleurs un maudit. Maudit par les réfugiés russes blancs qui l’accusent de tous les forfaits. Maudit par le parti communiste et ses nombreux sympathisants. Face au succès de la révolution bolchevique, il apparait comme un contre-révolutionnaire.

Avec sa femme Galina et leur fille Lucia, il habite une seule pièce d’un appartement situé rue Diderot, où Archinov et sa famille sont également installés. Archinov et lui gagnent péniblement leur vie à fabriquer les chaussures. Puis il devient manœuvre aux usines Renault, à Billancourt.

Un roman de Kessel, “Makhno et sa juive,” lui redonne à Paris célébrité sulfureuse. Le livre accuse notamment Makhno d’antisémitisme. Dans L’Humanité, Henri Barbusse écrit: «Ce livre relate les hauts faits sanglants du chef de bande Makhno, voleur et assassin de paisibles populations, qui commit avec un sadisme fou les plus abominables attentats et qui, parait-il, se prélase en ce moment chez nous, après avoir eu la chance d’échapper à l’Armée rouge.»

«Se prélasse»… Alors que Makhno vit un exil atroce, solitaire, désespéré, parlant mal le français, abandonné par sa femme. Sa légende effraie nombre de libertaires, heurtés par la violence de sa révolte. Toutefois, bien que pacifiste intégral, Louis Lecoin intervient auprès du préfet de police pour éviter l’expulsion de Makhno.

Devenu à la fois un mythe et un clochard, Makhno jalouse Voline qui s’est fait l’historien de la Makhnovtchina. Il ne réussit à survivre que par le comité fondé par “Le Libertaire” afin de lui assurer quelques ressources. Le 15 juin 1931, salle Lancry, les anarchistes français organisent une «grande fête de solidarité» pour Makhno.

Le 16 mars 1934, handicapé par ses blessures de guerre, il entre comme indigent à l’hôpital Tenon et y meurt tuberculeux.

En 1926, Makhno avait publié sa biographie en feuilleton dans “Le Libertaire.” En 1984, Alexandre Skirda traduisit et réunit des écrits de Makhno, de 1925 à 1932 : “La Lutte contre l’État et autres écrits.”

La première biographie de Makhno a été publié par Malcolm Menzies: “Makhno, une épopée” (1972). L’ouvrage capital sur la Makhnovitchina est “La Révolution inconnue” de Voline (1969 et 1986). Alexandra Skirda (né en 1942) est certainement le meilleure spécialiste et traducteur de l’épopée de Makhno. Sa biographie, “Nestor Makhno, le cosaque libertaire” (1982 et 1999) fait autorité.

English translation of Michel Ragon’s text from “The Dictionary of Anarchism” (copyright 2008 Albin Michel, Paris) by Paul Ben-Itzak, preceded by translator’s introduction:

If we’ve decided today to publish this excerpt from Michel Ragon‘s “Dictionnaire de l’Anarchie” (copyright Editions Albin Michel, Paris, 2008), this should not be construed in any manner as an endorsement of Nestor Makhno’s anti-State ideas or violent methods and tactics. (On which subject we have no expertise from which to evaluate their existence.) In either instance this is not the case. Rather, it’s because in Nestor Makhno’s story, as recounted by the late Michel Ragon — who also writes about Makhno in his historical novel “The Book of the Vanquished” — above all his simultaneously facing down both the White Army and Trotsky’s Red Army! — there’s inspiration aplenty for a new generation of Ukrainians fighting for their very existence against an invading Russian super-power. And because the very fact that he was fighting for Ukraine’s independence more than 100 years ago puts the lie to Vladimir Putin’s statement that Ukraine is a Bolshevik invention; au contraire! — Paul Ben-Itzak

The son of impoverished Ukrainians, Nestor Makhno started working as an apprentice in a foundry, then as an assistant wine merchant. In 1906, he joined up with a group of anarchist-communist peasants in Goulaiaïa-Polié. The following year, at the age of 18, he began a life of terrorist clandestinity. Arrested and tortured, he was condemned to death in 1910, a sentence commuted to forced labor in perpetuity. Transferred to the infamous Boutirky prison in Moscow, Makhno met Archinov, who introduced him to surreptitiously published illegal literature. It was in prison that Makhno received his political education. From Bakunin he retained this: “The passion for destruction is a creative passion.”

After six years of reclusion, Makhno was liberated in 1917 by the revolution. Returning to Ukraine, he rejected the autonomist movement. Contrary to the accusations of the Bolshevicks, who looked upon the peasantry as incurably reactionary and petite-bourgeoisie, Makhno believed only in the insurrection of the peasants, attached to their villages, and an autonomous revolutionary movement of the peasants.

Fresh out of prison, he founded the Peasant Association of Goulaiaïa-Polié, calling for the abolition of the State and of all political parties. He expropriated the large land holdings, drove the bosses out of their factories and founded agricultural communes.

His authority was rapidly contested by Petrograd, hostile to Ukrainian separatism. Archinov, who came to join him, advised him to visit Kropotkin, who had returned to Russia. But this last had no program. So Makhno decided to meet with Lenin, who received him in the Kremlin for an hour and tried to dissuade him from pursuing the Libertarian* path. “The anarchists,” Lenin told him, “are full of self-abnegation, they’re prepared for any sacrifice, but, fanatic and blind, they ignore the present to concentrate on a far-off future…. I consider you, comrade, to be a man possessing a sense of the realities and necessities of our epoch. If Russia had but a third of anarchists like you, we, the Communists, would be ready to work with them.” Makhno protested: “You Socialists don’t exist, so to speak, at all in our rural areas. Practically all the communes or peasant associations in Ukraine have been formed at the instigation of anarchist-communists.”

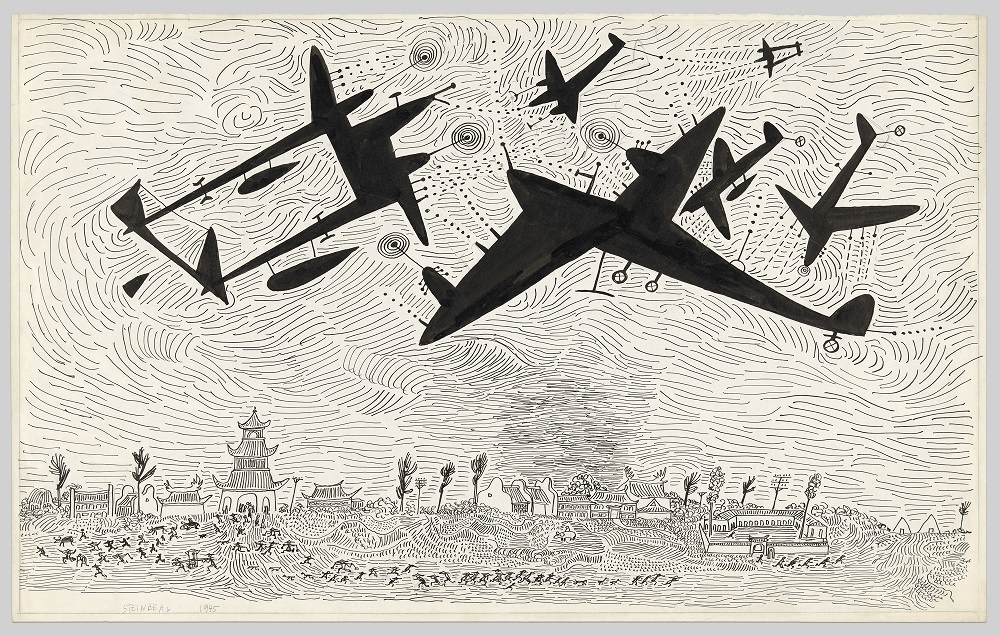

In the spring of 1918, Makhno set off the Ukrainian peasant revolt. He attacked the military posts of the German and Austro-Hungarian occupants, the large agricultural proprieties, and the Kulak farms. His cavalry created the surprise effect with their rapidity, in the grand tradition of the Cossacks.

In October 1918, Goulaiaïa-Polié was liberated. The Austrian officers taken prisoner were executed, the spared soldiers joined Makhno’s troops, but on February 6, the Red Army entered Kiev. Makhno, with his black** flags, retreated to the South.

In the fall of 1918, the activist newspaper “Nabat” (The Alarm), adopting the perspective that the Ukrainian revolution could rapidly become anarchist, set up its centers in Odessa. Archinov, Aaron Baron, and Voline, eminent anarchist theorists, joined Makhno, taking charge of propaganda and education. However, and despite the friendship Voline and Archinov bore him until the end of his life, in exile, Makhno always nurtured a suspicion, even jealousy, towards anarchist intellectuals.

In the spring of 1919, the man the insurgent peasants affectionately referred to as “Batko” (Little Father) assembled an army of 20,000 fighters. But the insurgent army of Ukraine had to simultaneously fight off Denikin’s Tsarist troops and Trotsky’s Red Army. Confronted with the danger represented by Denikin, Trotsky signed a pact of joint military action between his army and Makhno’s.

The extraordinary courage of Makhno, who personally took charge of the most dangerous operations, has been underscored by all historians. “It seemed,” Archinov would later write, “that this man of diminutive stature was made up of particularly tenacious components. He did not recede before any obstacle…. His calm was prodigious. He seemed oblivious to the thousands of projectiles raining down on the insurgent troops and the imminent danger of being wiped out at any moment by the heavily armed Russian troops.” His method: speed and surprise. Infantry wagons followed the cavalry.

After the shared victory of the Bolshevick troops and the anarchists against the annihilated White Army, Voroshilov ordered Makhno to redirect his offensive against Poland. Makhno recognized the trap, which consisted of getting the Ukrainian insurgents to emerge from their hide-out. He refused. Besides, he didn’t have any orders to take from a Bolshevick general.

In January 1920, the Communist party declared Makhno and his partisans outlaws. Eight months of fierce battles pitting Reds against Blacks** followed. On November 25, Trotsky invited the main Makhnovista commanders to a meeting of reconciliation in the Crimee. It was a trap. They were all arrested and executed, the Cavalry of the Crimee eviscerated.

The remaining units of the Makhnovitchina were ordered to integrate the Red army. Makhno found himself with 200 cavaliers in Goulaiaïa-Polié. He avoided being surrounded by the Red Army and, for eight months, tracked like an animal, in the harsh winter, abandoned little by little his artillery, his wagons, and his stock of provisions. Seriously injured, he was transported by his troops in a sleigh. On April 13, accompanied by 100 surviving cavaliers, he crossed the Dniester and took refuge in Bessarabia.

In exile, Makhno’s life henceforth would be that of a vanquished, of an invalid, weakened by numerous wounds. In the spring of 1922, he escaped Romania and entered Poland. The Soviet government, which had sentenced Makhno to death in absentia, requested his extradition. The international anarchist organizations got him a visa for Berlin, where he was reunited with Voline. In 1924, Voline, who had emigrated to France, prepared Makhno’s transfer.

French anarchists welcomed him with enthusiasm. But they were startled by his physical deterioration. Moreover, among the Russian refugees in Paris, Makhno was regarded as the devil. The devil for the White Russian refugees, who accused him of every crime under the Sun. The devil for the Communist Party and its numerous sympathizers. In the face of the success of the Bolshevick revolution, he was considered a counter-revolutionary.

With his wife Galina and their daughter Lucia, Makhno inhabited a one-room apartment on the rue Diderot, where Archinov and his family were also installed. He and Archinov barely eked out a living as shoemakers. Then he became a day laborer in the Renault factories in Billancourt, outside Paris.

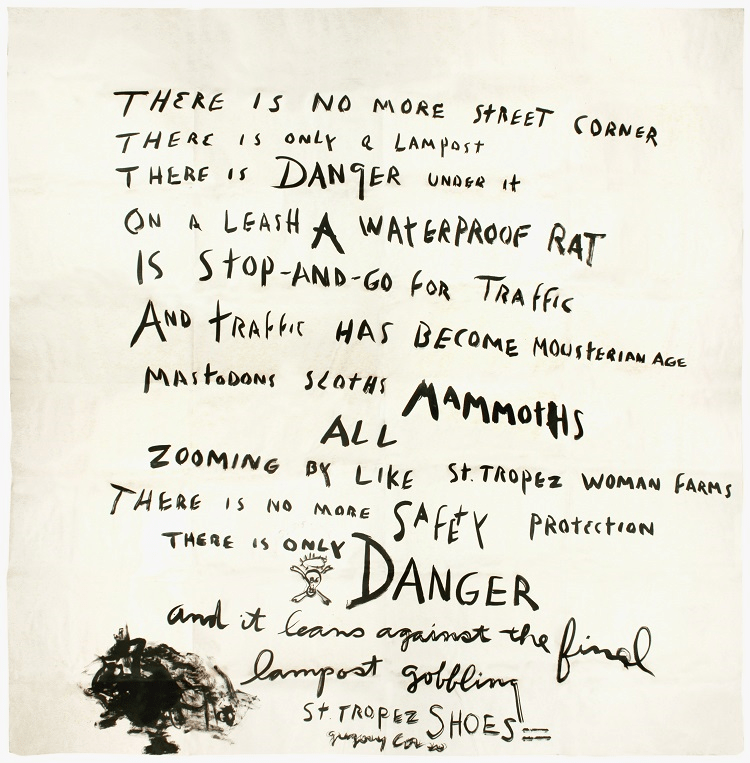

A novel by Joseph Kessel, “Makhno and his Jewess,” leant him a new, sulfurous celebrity in Paris. In the Communist newspaper “L’Humanité,” Henri Barbusse wrote: “This book relates the bloody deeds of the leader of the Makhno gang, a thief and killer of peaceful populations, who committed with a crazy sadism the most abominable attacks and who, it seems, is now basking in the Sun chez nous, after having had the luck to escape the Red Army.”

“Basking….” At a time when Makhno was living an atrocious, lonely, desperate exile, speaking French with difficulty, abandoned by his wife. His legend frightened a number of Libertarians*, struck by the violence of his rebellion. Even so, and despite being a complete pacifist, Louis Lecoin interceded with the Prefect of Police to head off Makhno’s expulsion from France.

Become simultaneously a legend and a member of the down-and-out, Makhno was jealous of Voline, who had made himself the historian of the Makhnovitchina. He managed to survive only grace of the committee founded by “Le Libertaire*” newspaper to provide him with some personal resources. On June 15, 1931, in the Lancry Hall near the Canal Saint-Martin, French anarchists organized a “grande fête of solidarity” for Makhno.

On March 16, 1934, handicapped by his war wounds, Nestor Makhno entered the indigent ward of the hospital Tenon and died, stricken by tuberculosis.

In 1926, Makhno had published his biography in serial form in “Le Libertaire.” In 1984, Alexandre Skirda translated and assembled Makhno’s writings from 1925 through 1932: “The struggle against the State and other writings.”

The first biography of Makhno was published by Malcolm Menzies: “Makhno, an Epic” (1972). The most important work on the Makhnovitchina is Voline’s “The Unknown Revolution” (1969 and 1986). Alexandre Skirda (born in 1942) is certainly the leading specialist and translator of the Makhno epic. His biography, “Nestor Makhno, the Libertarian* Cossack” (1982 and 1999) is authoritative.

*The French sense of the term Libertarian (Libertaire) is not the same as the American; it is practically synonymous with anarchism, in its non-violent forms.

**Anarchists, with whom the black flag is typically associated.