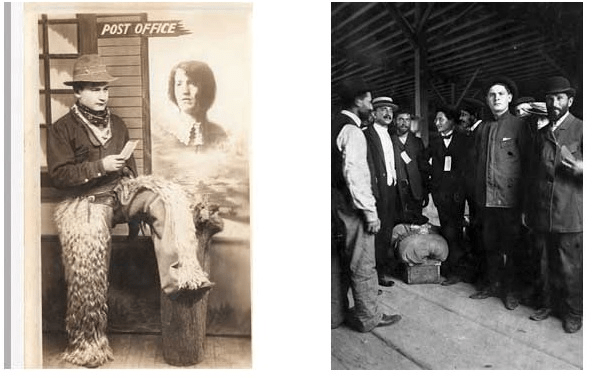

From the Arts Voyager Archives and the 2012 exhibition Forgotten Gateway: Coming to America Through Galveston Island. Images courtesy Fort Worth Museum of Science and History.

“The picture you’re seeing is of men on horseback whipping black bodies. The world is watching and that is the picture they are seeing.”

— Garlene Joseph, Haitian Bridge Alliance, September 20, 2021, Democracy Now, describing the scene in Del Rio, Texas, where mounted U.S. Border control agents turned their reigns into whips to coral would be Haitian asylum seekers back to Mexico.

“Dans le nom de la France, je vous demande pardon.”

— French president Emmanuel Macron, requesting forgiveness from the survivors and descendants of 200,000 indigenous French citizens who fought on the side of France during the Algerian War of Independence, September 20, 2021, Paris.

by Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2021 Paul Ben-Itzak

Give me your tired and your weak … so I can whip their Black asses back to Haiti

FORT WORTH, Texas – It has always been like this. If you had to pick one geographical point in the United States that symbolizes the often diametrically opposed way our country has viewed immigrants of color and immigrants of European descent, it just might be Texas. First there were the slaves, arriving in chains at Galveston Island beginning in 1845. (Texas would also be the last place where the slaves were informed they were free … after the Civil War ended.) Then there were the European whites who not only chose to immigrate, through 1924, but who were enticed to do so by the State of Texas, which launched a campaign to bring a million immigrants to the state through the port of Galveston Island. The railway companies even pitched in, offering free jump on, jump off privileges so that the immigrants could explore the Lone Star state at their leisure to find a place to settle, where low-cost housing and land were usually awaiting them. About the only white immigrants who eventually had trouble getting in – after 1913, when the rules got stricter – were people like me: Jews, who some immigration officials claimed were shifty.

Ironically, the more than 14,000 dark-skinned migrants who have flocked to the Texas border town of Del Rio, hovering and hungry under a bridge, some only to be beaten back by cowboy-border guards using their reigns as whips (and some to be aided by other Texans) over the past week trace their origins to Haiti, the first country founded by former slaves. “Trace” because some of the children, now among the hundreds being flown back there daily, have never seen the country, many of these migrants having started their long journey a decade or longer ago, settling first in Brazil, where their skin color wasn’t a problem and where they were welcomed, then migrating to Chili and finally Mexico, which also initially set up programs to integrate them. As noted by the Miami Herald’s Jacqueline Charles (to whose comments on Democracy Now’s Monday edition I owe this account of their trajectory), it was a word-of-mouth rumor that the Del Rio crossing was open that finally got them rushing to the U.S. border to request asylum…. In other words, it might be argued that these are not political but economic refugees. To my mind this distinction, sometimes employed in Europe to sort out theoretically more meritorious refugees from those who just need work, is a false dichotomy; if you’re starving because conditions (more and more driven by the climate emergency, often driven by Western interventions) have you out of work, your life – and your children’s future – isn’t any more secure than if you’re being politically persecuted. While this nuance might be reasonably debated in Europe, where immigration policies are geared towards political refugees and which generally does not have ‘land of immigrants’ in its DNA, it doesn’t really hold water in the U.S., whose (French-built) Statue of Liberty proclaims: “Give me your tired, your poor, your weak….” And the Biden administration’s specific expulsion approach – to fly these refugees, even the children who have never seen the country, back to what is once again the Wild West of Haiti, as opposed to, say, Brazil or Chili, where some of them already have legal status – effectively puts many of them back into the category of political refugees. “If I go back to Haiti,” said one man at the border, explaining why he had made the decision to just send his wife and children over the border to request asylum, with the likelihood that they would be flown back to Haiti and not crossed over himself, “I’d be killed (in Haiti).”

What’s also troubling is the legal mechanism the Biden administration is exploiting to justify expelling these migrants without a hearing (although in recent days U.S. immigration officials have suggested they could make their requests from abroad): A Trump-era measure which uses the Covid epidemic as grounds.

From the Arts Voyager Archives and the 2012 exhibition Forgotten Gateway: Coming to America Through Galveston Island.

“Je vous demande pardon.”

… Meanwhile, back in France, while President Biden was regressing and freshening up a policy of the predecessor he’d decried, French President Emmanuel Macron was following the just progression of steps taken by his three predecessors in granting escalating stages of recognition of how France had abandoned the Harkis – 200,000 indigenous Algerians with French citizenship who fought on France’s side during the Algerian war of Independence which ended with the country’s independence in 1962 — and upping the ante. 200,000 of these soldiers and their families were simply abandoned when French forces pulled out in 1962. 80,000 made their own way or were assisted to come to France, where they were often welcomed with squalid living conditions where they remained for years. Speaking in the presence of 120 Harkis and their descendants at the Elysee Palace Monday, Macron declared: “France has a debt towards them… To the abandoned combatants, to their families who were subjected to prison, I request forgiveness.” The French leader’s bold step – bold because it moved beyond “regrets,” bold because he himself, while calling colonialization a ‘crime against humanity’ during his 2017 presidential campaign and recognizing the need for reconciliation, had previously stopped short of apologizing for France’s colonial history with Algeria, emphasizing the need to move on – was accompanied by the concrete promise of a law for reconciliation and reparations, applicable not just to the surviving Harkis but their descendants. The young president – the first born after Algerian independence — personally approached one woman who had spoken out during his presentation, and who spent 10 years in a camp, took her hand and declared, “Je vous demande pardon Madame.”