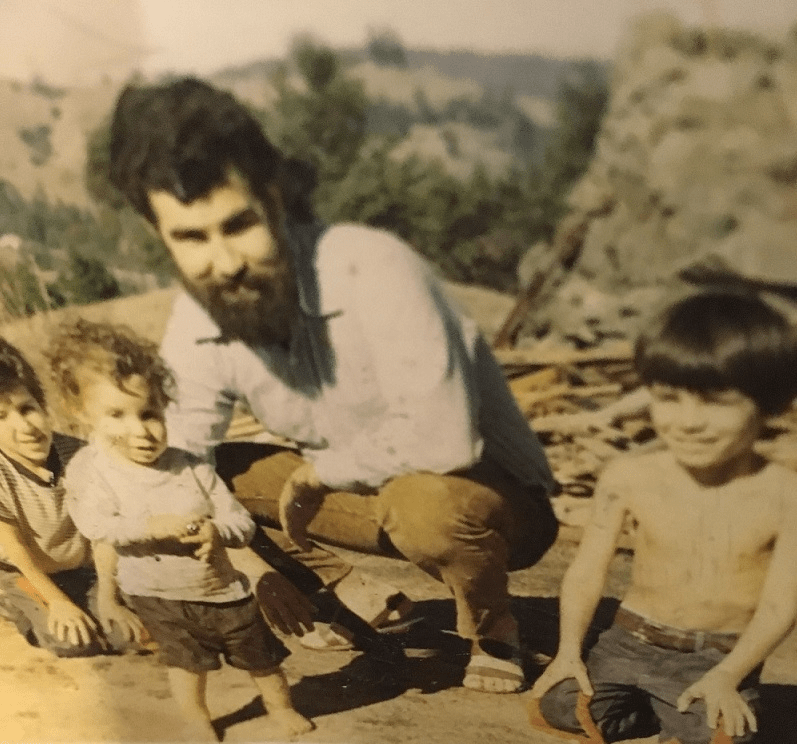

The author (far right) and his father and brothers near their home in rural – coastal Northern California circa Halloween 1969 (the scarlet strips are artisanal devils’ stripes). Photo: Eva Winer (now Wise).

by Paul Ivan Winer Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2022 Paul Ivan Winer Ben-Itzak

For “Stacy.”

My intrinsic belief in the virtue of vulnerability as the greatest gift one can offer another was seeded in a cluster of tall redwood trees nestled in the singed grass above Timber Cove, four years after the Great Northern California coastal fire of 1965. Stacy and I must have been eight years old.

“You mean you pick your nose too?”

I can’t remember whether it was Stacy (not her real name, simply because I haven’t asked her permission) or me who confessed first; what’s important is that we’d shared a secret habit that I at least was ashamed of. (And a penchant that seems to come back later in life; several years ago I noticed a Transatlantic tendency among acquaintances in their ’50s and ’60s to practice a form of public nose-picking where they seem to go into a trance while they’re talking to you, oblivious that they’re foraging in front of witnesses, and to the involuntarily diabolic looks that sometimes accompany the tic.) That with this confidence we’d suddenly become more intimate, removing a layer of protection. The confirmation/affirmation that we each had at least one person in our lives from whom we hid nothing and before whom we could (figuratively speaking) be naked and unguarded.

It was no surprise that this exchange of confidences came with Stacy; we’d been born in the same hospital, Marin General, at around the same time, under the same Taurean star (in the only year which reads the same if you turn the numerals upside down). If you can’t bare your soul with someone who’s already seen you in your original birthday suit on your actual birth day, there’s not much hope for you. (This is not to say that eight-year-old me was immune to complexes; 1969 also saw my first sexual hang-up and the first time I allowed fear to get in the way of pleasure: I refused to return to our Little Red Schoolhouse in Fort Ross after accidentally catching a glimpse of my teacher Mrs. Klein’s slip, and to bicycle through the valley that separated our house from my best friend George Bohan’s because it meant braving a meadow of wasps. I can’t remember if I was ever actually stung by a wasp, but I do recall, vividly and viscerally, being bit by a tic in a very pliant and private place while climbing on the rocks above the ocean the year before.)

By the time we shared our secret I’d already proposed to Stacy, when we were six, with a gold-painted plastic ring from Mr. Mopp’s in Berkeley. (I can’t remember her answer, though I do remember slipping it onto her finger.)

From our childhood, the handful of friezes of Stacy that have lingered include those captured in three photographic images:

** A Kodak shot with the colors fading of my mom in mod purple ’60s hip-hugging slacks and pink blouse arbitrating between us on the back of which my Mom has written (the photo was among a batch she sent my Miami Beach grandparents which my cousin Mindy retrieved after my grandmother’s death): “Paul and Stacy not talking to each other… again.” Stacy, turned away from me, is pouting under her short blonde hair; my expression under my Beatles mop-top is stoic and determined, trying to contain my upset behind a fixed upper lip, a facial position I still employ. We look to be about three or four.

** Two Edward Bigelow pictures from a book, “Come with me to nursery school,” published in 1970 by Holt, Rinehart, and Winston and whose photos had been taken in 1965 at the Mission Co-Op Nursery School on Potrero & 25th Street, run by a white-haired lady named Clara our first year, succeeded by Effie Schwartschild (whose adult son David would later disappear somewhere in the Australian Bush; we’d kept in touch, and her face would always bear this unresolved tragedy). In the first, Stacy is fighting off two schoolyard ruffians (one Black, one White) attempting to usurp her swing, kicking at them with all her might. Edith Thatcher Hurd’s caption reads: “At nursery school, we like to ride on the swing. Can you tell whose turn it is now?” In the second, Stacy and Jennifer (another of my ‘girlfriends,’ this one brown-haired), in potato-painting (we used the halved spuds as stamps) smocks, are cuddling a rabbit. (In another photo featured in the book, I am the highest among a group of boys climbing a tree, visioning the top with a determined if grim expression, another visage I would retain, even if I was destined to tumble from that tree numerous times over the next 50 years; Weebles Wobble but they don’t fall down.)

(Speaking of trees, among the books Stacy’s father Bill would give me as a child, always accompanied by inspiring, hopeful inscriptions, was Shel Silverstein‘s “The Giving Tree.”)

The next to last time I saw Stacy was also my first formal date, at age 14, to which I’d asked Stacy after running into her at an ice cream parlor in Rockridge where I was celebrating my birthday with current friends Maia Schneider and Chip Williams (who was supposed to die of a brain tumor by age 20; I have not heard from him since high school). Stacy, by then a svelte champion swimmer with sun-browned skin and long blonde hair, had grown up to be the kind of girl the Beach Boys wrote songs about. I was hopelessly smitten.

The date — one of our parents, Stacy’s mom Patty I think, dropped us off and the other picked us up — was at a Berkeley movie theater which was showing a double-feature of “Tommy” and “Alice’s Restaurant.” Some six years after our soul-baring nose-picking confessions, a layer of archetypal teenage boy-girl subterfuge had been acquired, taking form in my classic boy date maneuver of stretching my arms oh-so-nonchalantly as if I were yawning and letting the left arm settle behind her seat, and Stacy’s classic girl defense tactic of just as subtly leaning forward.

The other memory of Stacy I retain from this period seems out of place, chronology-wise, because it involves an argument degenerating into grabbing and scratching, even if the image I have of us is as being between the ages of 12 and 15. It’s confounded with a memory of Stacy making an appearance at my 15th birthday party, and seeming somewhat out of place among my other guests, all current classmates, because she didn’t know them and I was trying to combine two universes. But perhaps the murkiness around these souvenirs is normal as they both took place in that psycho-familial netherworld of the family basement, here of our Edwardian home on 25th Street (the front re-painted in psychedelic patterns by my father, as had Stacy’s on the opposite hill of 25th Street been by hers; this was the age of the Godseye) in Noe Valley, burial ground of George Washington Carver, my black-and-white pet rat, last seen scurrying behind the non-functioning fireplace mantle of the living room just above the basement, and of myriad ping-pong balls abandoned between the crevices which surrounded the concrete floor. (The ping-pong table had been the arena in which I’d proved my devotion to Christine LaMar, a sixth-grade crush at Rooftop School with whom I used to engage in stare-out contests on the 24 Divisadero bus until the day she boarded at Castro & Market wearing dark glasses after a cornea operation and I couldn’t tell if I was winning or losing. I dedicated my first novel, “The Problem Cops,” about an inter-racial police team who solved racial problems — Christine was what we described then as ‘mulatto’ — to Christine. At the ping-pong table, I used to exasperate my brother A. and my best friend Eric by insisting on this ritual pronouncement before each game: “This game is dedicated to Christine LaMar. If I win I will be __ and___ . If I lose I will be ___ and ___.” Christine was actually the first girl I called up, after looking up her number in the phone book and working up my courage by reciting it repeatedly before I was able to pick up the receiver. ((587-81__, and nearly 50 years later, I didn’t have to look it up.)) By the time Christine broke my heart by transferring to another school mid-way through the year, and after futilely trying to drown my sorrows with a buttermilk donut from the Castro Bakery before we transferred to the 35 Eureka, I was able to declare, through the salty tears, “If I win I will be 187 and 9,” which I did and was. Not that all that dedication was in vain ((to reference a song by Carly Simon, my other big crush that year; We have No Secrets, Reader, including that I still don’t know what ‘gavotte’ means)); that year I made it to the city-wide finals for the 9-12 age group before being demolished by a puny nine-year-old from Chinatown whose spin balls I could neither see nor touch.)

But to get back to Stacy and what must have been the last time I saw her, my 15th birthday, celebrated in the orange-shag-carpeted room my parents had carved out for me in the basement next to the ping-pong table (kind of like Greg Brady getting his own apartment in the attic during the last season — except for the tiny hole in the ceiling through which one could see the room from the kitchen — and just about the only way we matched the Bradys): In a way Stacy (at that point a cross between Marcia and Jan) handed me off — or relayed me — to the next girlfriend, Lisa Applebottom (not her real last name), another California blonde, who was among my James Lick Junior High friends assembled at the same party, with whom my first intimate exchange that same night marked a degrading of the male-female trust quotient that had made a breakthrough with Stacy in that cluster of trees.

After a round of Truth or Dare in which I’d answered the question “Who in this room do you like the most?” (Stacy had already left) with “Lisa” (although I may have already been ‘settling,’ which would establish itself as a disturbing pattern through at least 2019 in Paris, convinced that my real heart-throb, Felicia French — that is her real name, trop beau to disguise — was an impossible dream. Especially since the day she and Linda Mull had presented me with a baby-blue tee-shirt inscribed in black felt letters “Monster Boy,” the soubriquet they’d given me and even serenaded me with whenever they saw me coming down the hallway, to the tune of “Soldier Boy.” ((If Santana’d still been there — he’d graduated from James Lick ten years earlier — he could have accompanied the ballad on his guitar.)) Because Lisa was teased by the other girls ((and boys)) as being “flat-chested,” I thought I might have a better chance with her — not because she was flat-chested or not pretty ((she was)) but because she was the underdog and thus theoretically more attainable than Felicia.) and after Lisa (we’re back at my 15th birthday party) had taken me aside to whisper: “Remember what you said? It’s the same for me,” we found ourselves sequestered in the miniscule, low-ceilinged dark coat closet under the living room stairs above the basement. Unzipping my moche red and white striped ’70s track-suit jacket in the pitch dark, I’d felt the need to reassure Lisa (more sex hang-ups): “It’s my jacket.”

Lisa was at the origin of my ardor for the female tummy, the farthest we got, after a dare at another party, in Linda’s tree-house on Caselli Street, and during a rendez-vous in the woods of Glen Park Canyon, where I don’t remember if it was her scruples, my cumbersome black-and-white Oshkosh-be-gosh overall straps, or the thought that her gun-toting father might have me in his sights from their house on the rim of the canyon above that kept us from going any farther. (It had been in the nearby Glen Park club-house that I had first met, and fallen in love with, Felicia, when we were both 13.) If our relationship did not last out the summer after junior high graduation — our telephone conversations, usually initiated by me, quickly degenerated into Lisa’s bored “What else?”‘s, and she refused to play tennis with me anymore in the courts of cavernous concrete McAteer High School because “you’re bringing my game down” (she was a city champion) — I still have the proof that I was loved, in an autograph scrawled around her head-shot in the James Lick 1976 yearbook: “As Fi says, you are the love of my life. I will never forget you.”

“Fi” was Felicia, and what I remember most about our relationship — what I relished — is our three-hour telephone conversations (during which I often took refuge in the hall coat closet, whose darkness augmented their intimacy), including one in which she told me about a dream she’d had of me involving a bubble bath (or it may have been that while we were talking she told me that she was taking a bubble-bath, more in a spirit of comfortable trust than titilation) and an and interaction between us that was both intimate and somber. (I am being oblique because if I got more specific, I’d be violating the intimacy of our closet confidences… which I must include in this story because they signal a last youthful gift and boy-girl exchange of vulnerabilty and trust, Felicia’s confidence that she could guilelessly reveal dreaming of an intimate interaction between us with no fear that I would exploit or misinterpret it, transforming an imaginary oneric physical intimacy into a real-life intimacy of our young souls.)

Felicia also starred in my first grown-up play, the Tennessee Williams one-act “This Property is Condemned,” in which my “Boy” was the foil to her “Girl,” my big line being “The BONE Orchard?!,” uttered after the Girl, balancing on the rusted tracks of an abandoned train line while she relates the sad saga of her older sister Alma, announces where Alma is now (the Bone Orchard), a tale intertwined with a capella singing (I can hear Felicia still):

“Wish me a Rainbow

And wish me a Star

A wish you can give me

Wherever you are

With stars for my pillow

And dreams for my eyes

And a make-believe ball where

Our love wins first prize.”

Williams allowed the play to be made into a movie in which Alma was brought to life by Nathalie Wood, whose big and bright-eyed beauty was mirrored by Felicia. I won the two-person contest for best supporting actor, only one other junior high having shown up for the competition our one-act was created for, my opponent being the ill-fated Chip. Felicia also played the lead in the drama club’s production for that year, Maxwell Anderson’s “The Bad Seed,” about a sweet little girl who goes around killing people she doesn’t like. (Two years later, “This Property is Condemned” would be the first play I would direct, as a student at Lewis Campbell’s Center for Theater Training, a FAME-like city-wide program based at Mission High, with another Stacy ((her real name)) whom I’d known since 1972 when we acted together in the Lone Mountain College summer program’s production of “Mutiny in Space,” taking Felicia’s place until I cruelly replaced her for missing a rehearsal or two, exhibiting absolutely no compassion for her complicated life. And my hurtful, fear-based treatment did not stop there: Later I would exclude Stacy (the one for whom this is the real name) from my unchaperoned cast party because of the havoc my square mind imagined her older punk-rocker boyfriend “Bangs” might wreak on the house.)

In an echo of Christine LaMar’s transfer, I was devastated when I learned over the summer after junior high graduation — in a postcard sent to me at Camp Tawonga in the High Sierras, where I was busy having other romantic adventures I won’t go into here to spare you another long parenthetical digression — that Felicia would not be joining me at “Smack,” as we called the concrete prison-like, asbestos-drenched, sunken complex that was McAteer, but would be going to Lowell, the school for smarties.

The last time I saw Felicia must have been in the early ’90s, because it was when I was back renting an apartment my dad and step-mom had carved out of our childhood home in a former drugstore-soda fountain on Guerrero Street (the same one I’d excluded Stacy-it’s-her-real-name and her boyfriend Bangs from, where Dad and Lulu had set up house after he and Mom separated), and I ran into her hanging out up top the 24th Street BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) station. If I didn’t ask for a number, it was probably because of the lackadaisical fashion in which Felicia’d greeted me, as if we’d only just seen each other yesterday (or as if I was not as significant for her as she had been to me).

Recent searches for “Felicia French” and for Lisa on Facebook have proved fruitless.

I have, however, been able to retrieve “Stacy” the-one-I-was-born-with (and, through her, her father Bill; Patty unfortunately passed away, Stacy learned me, in 2020, a year after my father), and the other Stacy (the one who’s real name it is) is now the friend I’ve stayed in touch with the longest, since our “Mutiny in Space.” Besides of course the “Stacy” I was born next to.

“Stacy” who, it seems, has been able to retain her precious (I don’t use the adjective sarcastically) gift of vulnerability.

“Stacy” who, I hope, will understand that if I have shared our childhood sharing (and scuffling) now it is because I am tired of writing these tributes — for a tribute is what this is — after the person is already gone and it is too late. (Aging children, I am one.)

For my part, and despite numerous subsequent relationships in recent years where (in my jaundiced view) the girl has taken advantage of the gift of vulnerability I offered and (however unintentionally) (another thing I remember about Camp Tawonga is how a counselor told me, as we were hiking through Yosemite, that I was a “real diplomat”) cruelly twisted it in my heart like a dagger, and despite well-meaning warnings that I need to “protect myself” better from getting wounds far more pernicious than any scratch-marks “Stacy” and I might have inflicted on each other, I am still determined not to lose that vulnerability and to bear it like the gift it is — beating, like Gatsby, against the tide.

*The title is taken from the song title and lyric by Joni Mitchell, from the young man’s funeral scene in “Alice’s Restaurant,” and which you can find online. Joni Mitchell who, with Neil Young — another aging child still teaching after all these years — recently made headlines by withdrawing her songs from the online streaming website Spotify when it wouldn’t stop broadcasting lethal anti-vaccine propaganda.