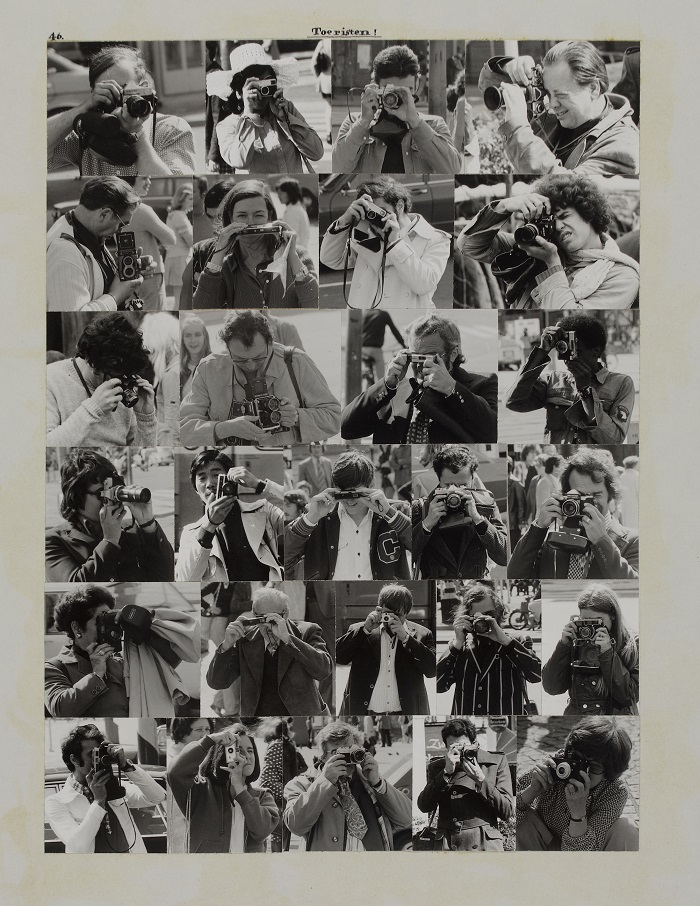

Running tomorrow through April 29 at the Pompidou Centre, “Jos Houweling, Amsterdam Seventies” features 233 photo-collages many of which were published in the 1975 “700 centenboek Amsterdam” to fete the canal city’s 700th birthday. Above: Jos Houweling,”Toeristen! (Tourists!).” Taken from “700 centenboek Amsterdam,” 1975. Photos glued on cardboard, prints silver-gelatin. ©Centre Pompidou. Photograph of photo-collage: G. Meguerditchian / Dist. RMn-Gp. ©Jos Houweling.

Running tomorrow through April 29 at the Pompidou Centre, “Jos Houweling, Amsterdam Seventies” features 233 photo-collages many of which were published in the 1975 “700 centenboek Amsterdam” to fete the canal city’s 700th birthday. Above: Jos Houweling,”Toeristen! (Tourists!).” Taken from “700 centenboek Amsterdam,” 1975. Photos glued on cardboard, prints silver-gelatin. ©Centre Pompidou. Photograph of photo-collage: G. Meguerditchian / Dist. RMn-Gp. ©Jos Houweling.

Art will save us: Jasper Johns, 1961

Among the 44 newly exhibited contemporary masterpieces transforming the presentation of the Art Institute of Chicago’s contemporary collection is, above, Jasper Johns, “Target,” 1961. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Edlis / Neeson Collection. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Among the 44 newly exhibited contemporary masterpieces transforming the presentation of the Art Institute of Chicago’s contemporary collection is, above, Jasper Johns, “Target,” 1961. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Edlis / Neeson Collection. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Amélie’s got a gun, just like Patty – Lola Lafon conjures Hearst and illuminates a modern phenomenon

By Lola Lafon, as translated by Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright Actes Sud; translation copyright Paul Ben-Itzak

“Heartless powers try to tell us what to think

If the spirit’s sleeping then the flesh is ink

History’s page will be neatly carved in stone

The future’s here, we are it, we are on our own

On our own, on our own, we are on our own.”

— “Throwing Stones,” lyrics by John Perry Barlow, songwriter for the Grateful Dead and visionary co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. (Click here to listen.)

“You know what your daddy said, Patty? He said, well, sixty days ago she was such a lovely child and now here she is with a gun in her hands.”

— Patti Smith’s cover of Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Joe,” cited by Lola Lafon in “Mercy Mary Patty”

“Qu’on se moque pas de mon âme.” (Don’t mock my soul)

— Lola Lafon, “Mon Ame,” from the album “Grandir a l’envers de rien” (Growing up on the other side of nothing) (Recording here.)

“Je suis perdu, je suis revenu.” (I’m lost, I’ve returned)

— Lola Lafon, ibid

(Like what you’re reading? Please let us know by making a donation so that we can continue this work. Please designate your PayPal donation to paulbenitzak@gmail.com , or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. Patricia Hearst was kidnapped from her apartment in Berkeley, California 45 years ago today.)

Photo of Lola Lafon by and copyright Lynne S.K., and courtesy Actes-Sud.

Translator’s note: If the ‘you’ addressed by Lola Lafon’s narrator is Neveva Gene, the fictional American professor teaching at a private women’s college in rural France who’s been hired by Patricia Hearst’s attorneys to analyze the Hearst coverage and the tape-recorded messages from Patty released by her kidnappers the “Symbionese Liberation Army” as they try to prove she was brainwashed or coerced into participating in the SLA crimes, this is not a case of the author pretending to be the interior voice of her protagonist. There’s a practical explanation: As becomes clear over the course of the book, the narrator grew up as one of the adopted charges of the adult Violaine, subsequent to the latter’s apprenticeship with Neveva in 1974. During that apprenticeship — while working on the Hearst brief – the French teenager kept a diary. So when the narrator, finding her way to Smith College in 2015 (see first excerpt below) explains (still addressing Gene), “I’m not looking for you, I’m supposing you (emphasis added),” she means that she’s supposing Neveva – and the details of her collaboration with the French teenager Violaine on the Hearst case and their ensuing relationship which form the bulk of the novel – based on what Violaine has told her and on her own reading and interpretation of Violaine’s notes. (In addressing Gene in the second person, Lafon employs the formal “vous,” thus dispensing with any notion that she’s presuming to be the character’s interior voice.) I discovered Lola Lafon when her album Growing up on the other side of nothing was among a box of CDs left on the doorstep of my Belleville apartment building on November 12, 2015, the night before the terrorist attacks that killed 130 people in the music halls and stadiums and on the café terraces of Paris. Her music (see link below) accompanied me during the soul-wrenching days, weeks, and months that followed. So when I heard that Lafon had taken on an episode of my own youth in San Francisco of 1974-75 — in part as a way, in my interpretation, to understand what was happening to too many youth in my Paris of 2015 — I had to find out what she had to say. In “Mary Mercy Patty” Lafon reveals things about my own self — and the impact the Hearst episode had on the fragile pre-adolescent I was — that I hadn’t previously seen. )

In this world where everything is manipulated, where the only thing that can’t be split up is money, and where the heart is rent in half, you can’t rest neutrally on the sidelines.

–Paul Nizan, “La Conspiration,” cited on the frontispiece of “Mercy Mary Patty”

You write of the disappearing teen-aged girls. You write of these missing persons who cut the umbilical cord to search out new vistas without the ability to sort the good from the rotten, elusive, their minds shutting out adults. You question our brutal need to ‘just talk some sense into them.’ You write of the rage of these young people who, at night, in their bedrooms surrounded by stuffed animals, dream up victorious evasions, boarding dilapidated buses, trains, and strangers’ cars, abandoning the neatly paved road for the rubble.

“Mercy Mary Patty,” your study published in 1977 in the U.S., which has just been re-issued, augmented with a new preface by you and a brief publisher’s note, is dedicated to them. It’s not yet been translated into French. It concludes with acknowledgments as well as your résumé, from your degrees in American Literature, History, and Sociology through your teaching positions: the University of Chicago in 1973, the College of the Dunes, France, in 1974-75, assistant professor at the University of Bologna in 1982 and, finally, professor at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. Articles appearing in the academic revues over the past few months underline the importance of your research, magazines analyze what they dub your ‘rehabilitation.’ The New Yorker devotes two columns to you: “A controversial theory: Neveva Gene and the capsized teenaged girls, from Mercy Short** in 1690 to Patricia Hearst in 1974.” The Northampton bookstore clerk slips your book into a paper bag, he seems curious about my choice, the Hearst saga is old history, You’re European, aren’t you? You seem to have your own share of toxic teenagers at the moment, those girls swearing allegiance to a god like one idolizes a movie star, Marx, God, different eras, different tastes…. I’m guessing you’re a student at Smith, he goes on, if you’re looking to meet the author, she’s probably listed in the faculty directory.

But I’m not looking for you. Your office is on the second floor of the building I walk by every morning but it doesn’t matter because I’m not looking for you, I’m supposing you. I explain my reason for being here to the bookstore clerk, I pronounce your name, I recount, I refer to “Madame Neveva” as if you were standing right there next to us and insist upon it, I pronounce “Neveva” in the same way as your students in France who venerated you and who I was not one of, Neveva Gene who arrived in a village in Southwest France in the month of January 1974, a young teacher who in the autumn of 1974 hastily tacked up notices at the village’s two bakeries, Wanted female student with high level of spoken and written English, full-time job for 15 days. Adults need not apply. URGENT.

Chapter One

October 1975

The three girls who have responded to your notice are there, sitting across from you in your cramped office, you offer them a bag of peanuts and cashews, your knees bump up against the desk, your light blue Shetland sweater sports elbow patches, your hitched-up Levis reveal the malleoluses of your ankles. You say Bonjour, I’m Neveva Gene, pronounced ‘Gene’ as in Gene Kelly or Gene Tierney, no nick-names please, no ‘Gena,’ no ‘Jenny.’

Squeezed into a window nook, one by one the candidates rattle off their credentials in an effort to win you over, this one is studying English Literature at the university, the next has already been to the U.S. twice, speaking English fluently is important if you’re going to go into business. When it’s the third girl’s turn, she refers to taking a “pause” since graduating from high school in June and the need to make a little bread. As they already know, you’re a guest professor. You studied at Smith College in Massachusetts, a university founded in 1875 and reserved for girls barred at the time from higher education. Sylvia Plath was a student there. Sylvia Plath, the name doesn’t ring a bell to them? You mark an incredulous pause in the face of the embarrassed looks of the postulants. Margaret Mitchell? The author of “Gone with the Wind”? The young women acquiesce to that one with an enthusiasm which you find alarming, it’s a novel that’s more than a little dubious, above all Smith had the honor of admitting the first African-American woman to graduate from college, in 1900: Otelia Cromwell.

American Lifestyle and Culture, the course you’re teaching at the College of the Dunes, is multi-faceted; you rapidly enumerate what you’d anticipated teaching before you arrived, the distinct architecture of Massachusetts houses, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s letters to his daughter Scottie, the history of the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, an examination of the success of the film “The Planet of the Apes,” an explanation of the urban legend of the phantom hitch-hiker, the adventure of Apollo 16 and, finally, the invention of the Arpanet and its consequences for communication. Daunting program. The fact is that you harbored big hopes for this college. They should see the welcome brochure, three pages on pedagogic innovation, but the reality is something else, this institution is merely the umpteenth private school for girls without any particular qualities who drift aimlessly about after high school, a factory for future homemakers more hippy than their mothers, adorable domestic pets brought up to be consumed before their expiration dates. And who understand absolutely nothing in the articles you hand out. The young candidates say nothing and wait politely to find out what this has got to do with them, perhaps they didn’t get the sexual connotation of “brought up to be consumed.” Or maybe they’re just terrified now at the idea of being subjected to your judgment for this work about which you still haven’t said a word. One by one, they recite an article from the New York Times out loud, then translate the essentials, you ask them about the books they read, their musical tastes, pretend not to understand if they answer in French, Sorry?

But where did you learn to speak English like that, you ask the third candidate who immediately blushes, she refers to American songs whose lyrics she likes to copy, they’re actually British you point out, amused, when she recites the words from the Rolling Stones’s “Time Waits for No One” and David Bowie’s “Young Americans.” She lists her favorite movies, every week on the second public television channel a film is projected with sub-titles, the ciné-club, she never misses it even if it’s on late, 11 o’clock, you call her an Americanophile, she stammers, not sure if this is good or bad. All three listen to you, petrified, as you imitate the annual speech of the director to parents in an exageratedly nasal and mincing voice, “Oh nooo, it has nothing to do with not accepting boys in my establishment but offering girls special attention! To liberate them from their own fears!” You want to know their opinion: Would they like to study there, where one has access to so many courses, Introduction to Psychoanalysis, Cinema History, Introduction to Baroque Singing, Judo, and Modern Dance? The third girl’s answer — the tuition is too high — you greet with exaltation, as if it were a scientific breakthrough: Eggs-act-ly! Yes! The very principal of this establishment is a contradiction: Emancipate only those who have the means to be emancipated. At the end of the day, it’s just a bunch of bullshit. (In English in the original.)

Suddenly, you climb up onto the Plexiglas chair. You grab a box stored on the top shelf and place it on the desk. Voila, you announce in designating the package of American origin, as attested to by an impressive quantity of identical green stamps glued across the top of the box. The job of whoever you decide to hire is entirely contained within, you show them the folders overflowing with press clips, half open a plastic bag filled with cassette tapes resembling those teenagers use to record their favorite songs off the radio. You have to write a report, and you won’t have the time to read all this. You must be capable of synthesizing these tons of articles, you explain to them, pointing your finger at the box. You insist on an availability that will be indispensable but of a limited duration, 15 days maximum.

“In fact, do you know who Patricia Hearst is?” They’re on the landing when you pose the question, as if it’s an after-thought, one of the candidates hastens to answer: During her vacation in the U.S., she saw her on t.v., Patricia is very rich she was kidnapped and…. She’s cut off by her competition, yes they talked about her in France, there was a fusillade, a fire, and she was killed. No, you correct her, she’s alive, the police caught her. It’s the kidnappers who are dead. And you’ve been hired to evaluate the mental state of Patricia Hearst after all these tribulations. A respectful silence follows. None of the three ask about this mysterious “they” who have engaged your services or why “they” picked you, you whose specialties are history and literature. You’re the adult, the teacher, and also a foreigner inviting them into a world of adventure, kidnapping, heiresses, happy endings. That’s enough in itself. The young woman whose English level you praised hasn’t uttered a word, distressed, perhaps, to have lost out in the final leg of the race; she’s never heard of Patricia Hearst. That same night, her mother nudges her bedroom door open, her hand on the telephone: It’s for you, a funny accent, certainly the American professor.

“Is it accepted here to go to teachers’ homes?,” you ask the young woman you’ve annointed as your assistant. “Because in my office we’d be too scrunched up, we’ll be a lot more comfortable in my home. We’ll talk salary tomorrow, I’m counting on you to not let yourself be gypped. By the way, are you really 18? I’d put you more at 15.” And it doesn’t matter that she’s never heard of Patricia Hearst, you add before hanging up.

Chapter Two

During the rambling job interview — a real Show — you conveniently leave out a major chunk of the Hearst saga. Are you afraid of scaring off these three demeure French girls by telling them any more, do they seem too young to you, are you worried that their parents will be alarmed to see them working on such a subject? You’ve been living in this village of less than 5,000 habitants for a year and a half and have already tested its limits, here everyone knows everything, talks about everything, judges everything. It takes time to explain the complexities and nuances of the drama to your interlocutors and time is the one thing you don’t have a lot of. What angle of approach will you use to study the trajectory of this young American? Which episode will you start with?

That of the kidnapping of Patricia Hearst on February 4, 1974 by an obscure revolutionary cell, the Symbionese Liberation Army? That of the first message from the heiress of February 12, a tape recording deposited by her abductors at the entrance to a radical radio station which mesmerized the entire country, her feeble voice murmuring “Mom, Dad, I’m all right”? How to explain to these French girls just looking for work that in the eyes of the FBI, the victim metamorphosed into a perpetrator in less than two months; converted to the Marxist cause of her captors, she was even identified at their sides April 15 on the video-surveillance images from a San Francisco bank, armed with an M1. It’s understandable that you’re cautious about what the candidates know and don’t say anything about the metamorphosis of Patricia Hearst.

As for your task, the “psychological” evaluation, you don’t exactly lie but here as well you take shortcuts and consign Patricia’s lawyer, your client, to the shadows. You have just 15 days to find something in the cardboard box overflowing with Xeroxes that will help you write an expert report proving the innocence of this child over whom the American media is whipping up a frenzy as her trial date approaches. 15 days to determine, who is the real Patricia Hearst?: a Marxist terrorist, a lost co-ed, an authentic revolutionary, a poor little rich girl, an heiress on the lam, an empty-headed and banal personality who embraced a cause at random, a manipulated zombie, an angry young woman with her sights set on America?

Chapter Three

A large beige dog with chestnut spots greets your new assistant on the doorstep with boundless enthusiasm, you lean forward to hold him back — blech!, he’s just planted a sloppy wet kiss on me — a wink, Meet Lenny, you throw a sock at the dog so he’ll amscray.

You put some sugar-coated cookies out on a plate, offer a cup of tea, jasmine, mint, saveur Russe, it’s up to her, you indicate 10 scattered, slightly rusty tin boxes on the kitchen counter. She picks one at random, doesn’t dare tell you that in her family, whether it’s black tea or herbal tea, it’s only imbibed when one’s sick. Remaining standing, she listens to you, her cup in hand, you’ve not invited her to sit down and the only chair in the room is covered with sweaters, an amorphous pile.

“Summarizing the articles would be too fastidious, we need to concentrate on the details,” with a finger you pick at the frayed edges of the cardboard box posed on the dining room table. The French girl acquiesces, looking for signs, are you married, you’re not wearing any perfume, your face is a make-up free zone, the reddened nostrils testify to this, your hair is gathered up into a haphazard pony-tail, your nails clipped like a boy’s are yellowed with tobacco, you laugh with your mouth full of chewed-up cookies without excusing yourself, the beads of tangled necklaces peak out from a half-opened drawer; you tack 33 record covers on the wall, a Nina Simone and a Patti Smith, twice you allude to your “best friend” who lives in San Francisco, the expression suggests an extended adolescence, how old are you? The dog follows you everywhere, into the kitchen, the bathroom, when you go to the WC you continue talking to your assistant, yelling at her to answer the phone. Mlle Gene Neveva is not available, the flabbergasted girl improvises.

You’re the first American she’s ever met. Speaking this language that she associates with novels and movie stars, hearing her own voice become foreign makes your first day together an intoxicating role-playing game. Everything is part of the scenery, a stop-over in an exotic wonderland, the peanut butter you spread on the crackers whose pale crumbs are strewn all over the rug, your bedroom with the storm-windows shuttered in the daytime, the books piled up at the foot of your bed and the stacks of dailies and weeklies that you ask her to sort by name: Time, Newsweek, the New York Times, the San Francisco Chronicle. You toss around the words casually, kidnapping, FBI, abductors, when night falls, you rub your eyes like a tired child and twist around and contort your chest with the eyes half-closed, inhaling slowly, sitting Indian style on the floor. Re-invigorated, you marvel at the manila folders that the girl has prepared, as well as the neat rectangular white labels with sky-blue borders that she pulls out of her bag.

“I love how serious you are, Violette. That name doesn’t really fit you, ‘Violette,’ maybe because it makes you sound too much like a fragile flower….”

My middle name is Violaine, the teenager improvises. You skooch your legs under the table, your mouth forms a careful O, the smoke rings evaporating before they hit the ceiling.

“It’s important, a first name, it’s a birth. Violaine. Not easy to pronounce for an American but o-kay. You know, Vi-o-lai-nuh, what will remain unforgettable for me when I go back to the United States?”

The thunder-storms. The mountains. On the beach, on certain days, one can make them out etched into the fog, when they lock themselves around the ocean like an open hand it’s a good sign that it will be sunny the next day, your assistant is amused to hear you recite with such conviction the sayings of the old-timers.

The tidal equinoxes, also. Last week the ocean rose up to the level of the dunes! The paths along the moors. Absolutely identical, no point of reference, a pine tree is a pine tree is a pine tree is a fern tree is sand. The sand, you sigh…. That, mixed with the soil in the forest, which melts into mud the instant it rains, the silky beige sand that ends up embedded in your purse, encrusted in the spirals of your notebooks, stuck to the base of the bed, clinging to the soleus of your calves, rooted in your socks.

Mlle Neveva won’t forget the sand, she who’s just baptized herself Violaine notes in her journal with the detachment of a documentarian, omitting the fleeting moment when she thinks she hears you qualify her as unforgettable even though she barely knows you.

The sand, you repeat practically every day, exasperated, removing your tennis shoes and shaking them out over the ground.

Day 13

When, on the morning of the 13th day, you announce that you’ve read something which has opened your eyes, no doubt your report will be finished tomorrow afternoon, Violaine is more relieved than you can imagine. Her only wish is to get back to the equilibrium of those first days, to be your helping hand which cuts out the newspaper and magazine clippings, translates, and pastes. Rather than being the person who slows you down and annoys you and doesn’t hear the same thing you hear in Patty’s recorded messages. You suggest going to the village’s bar / smoke-shop, a change of ambiance will help.

It’s noon, people are emerging from the chapel, the church plaza is packed, Lenny goes wild every time a hand is stretched out to him, exuberant and shy at the same time, a little kid who you never let out of your sight, you whistle and put an end to the social whirl. You dismiss all these pious church-goers out loud in English, tell Violaine to note their holier-than-though airs, wearing their religion on their sleeves, they’re so relieved to be in good standing with God. There’s no such thing as lost souls, just passive bodies — our own.

When you walk into the café, the men aligned along the counter rivet their eyes on you, Violaine follows in your wake, embarrassed to be embarrassed by you who are not at all embarrassed, your jeans just a little too big reveal the hemline of your panties, your sea blue pull-over emphasizes that you’re not wearing a bra.

This providential book, you read it all in one night, the Stanislavski Method of the Actor’s Studio is the bible of all the big American actors, Robert de Niro used it for his approach to playing Travis McGee in “Taxi Driver” (Violaine hasn’t seen it, the film is banned for those under 21). It includes an abundance of exercises to aid in character-building. And without a doubt, Patricia has become a character. And voila your idea, to envisage the entire saga like a story, a film! You’ll portray Patricia and Violaine can play, let’s see, Emily Harris, of the SLA. Your assistant’s aghast refusal amuses you; what, Marxism isn’t contagious?!

“First exercise: Two words that define your character.”

“Alone,” Violaine suggests.

“Protected from everything. Oops, I used one word too many.”

“Too mature for her age.”

“Too many words, Violaine! Susceptible and superficial?”

“Secretive.”

“Typical teenager,” you fire back, sticking your tongue out at Violaine.

“A symbolic example.”

A symbolic example? Of what? Your assistant is talking nonsense, she has no idea, she’s simply parroting what the heiress says on the second tape. You admit that you’re perplexed, without doubt Patricia must have said “This is a symbolic example,” and Violaine must have understood “I am a symbolic example.” You’ll have to listen to it again later. Second exercise, write a letter to one’s character. How would a letter addressed to Patricia Hearst, college sophomore, be different from one addressed to Patricia Hearst, convict? One doesn’t change in a few weeks, Violaine protests, regretting all the same to find herself disagreeing with you yet again. You continue to insist that we’re not entities with immutable identities, circumstances change us, does Violaine act the same with her parents as here in the bar, certainly not, but Violaine sticks to her guns, Patricia doesn’t really change over the course of her messages, she’d write her the same letter.

The waiter buzzes about you, when he serves the glass of Armagnac the owner insists on offering — the American lady from the Dunes is spending the afternoon in his bar! — his wrist brushes against your hair, Violaine whispers to you, “Il tient une couche celui-là” (He’s one sick puppy, that one), you don’t know the expression but it enchants you, you repeat it to the waiter, who slinks away, the bar is full, the regulars just coming from the rugby match, teenagers putting off going home for the traditional Sunday lunch, you can’t hear anyone in all the hubbub, you step up to the counter to order a beer, you drink to the death of that bastard, Franco finally croaked the day before yesterday, you proclaim rather than simply state, “Those who are against fascism without being against capitalism, those who wail about barbary and who come from barbary, are like those who eat their share of veal then say calves shouldn’t be killed. They want to eat the veal but don’t want to see the blood.”

A young blonde man applauds you, Bravo, say that again but louder this time, so that everyone can hear, a couple approaches you and introduces themselves respectfully, their daughter is in your class, she talks about you all the time, you interrupt them, she should read Brecht, their daughter, voilà, the glasses are refilled and clinked, dirty fascists, then, in the midst of this mob, Violaine rises to her tippy-toes and whispers to you these words that she knows by heart, the phrase with which the SLA signs all its messages, “Death to the fascist insect who feeds on the life of the people.” You stare at her, amazed, she thinks you’re going to make fun of her and apologizes, she’s read the words so often in the past few days that they’ve become embedded in her brain, but you take hold of her hand and execute a rapid, exaggeratedly ceremonious kiss of the hand, everyone whistles for you, you graciously acknowledge them as in the theater.

You insist on walking Violaine home despite her protests, It’s not like she’s going to get lost over 500 meters. Weaving along the path, slightly buzzed, you burst out laughing, recalling the perturbed air of a group of your students, seeing you drinking with the farmers seemed to scandalize them, you regale Violaine with your impressions of them, the way one can never separate those two in class, the sadistic books that one devours, the stories of girls on drugs, prostituted, beaten, locked in closets, raped, the passion of that one for Arthur Rimbaud, she keeps a picture of him in her wallet and sobs over his death, but she’s incapable of citing a single one of his poems. Arriving at the gate, you can’t seem to decide to leave, you ask about the purpose of the high thickets which hide the property of Violaine’s parents. It’s a question of tranquility, Violaine answers without reflecting. You repeat the syllables, “tran-quil-i-ty.” Your assistant’s parents are therefore insulated from all the terrible racket which rages around here — you indicate with a large gesture the forest and the disparate other houses. You crack yourself up with your own jokes, do Violaine’s parents have a special thermostat in their salon for perfect tran-quil-i-ty, with different gradations: “bored like a dead man,” “death-like silence….” Violaine, her keys in hand, doesn’t dare tell you that she’s cold, that around these parts the expression is “bored like a dead rat” and that her parents are waiting, the living-room lights are on, if they come outside and find you both on the stoop, they’ll invite you in, and Violaine can’t think of anything worse than you meeting her parents, why do you have to endlessly analyze everything, you tilt your head and hoot at the sky, waiting for the theoretical reply of an owl which doesn’t come. As if it weren’t night, with the humid sand under your naked feet — you clutch your shoes in your hands, they clutch you — you start in on a recapitulation of the afternoon, it was groovy. You’ll go back to the bar next Sunday as promised with a Nina Simone 33 because you couldn’t find her songs in the jukebox. A propos, did Violaine notice what happened when you recounted how, during a Nina Simone concert, her parents had to give up their seats of honor to Whites and Nina refused to continue singing? Nothing. Nothing happened. Not a shadow of indignation.

The bar had never been so quiet. Violaine should remember it, this stillness, it has an acrid taste, it’s the silence of that which remains unspoken, those who didn’t flinch at the mention of concert seats being off-limits to Blacks thought they were abstaining from commenting but they said it all. In this café, everyone had chosen his camp. There’s no such thing as neutrality.

Day 14 (Excerpt)

Your faith in Method Acting doesn’t last long, the following morning you don’t talk about it anymore. You complain that you have at most two more days before you have to mail the report and you’ve really only just begun writing it. You hole up in your room for most of the day, from the living-room Violaine can hear the tape player starting up, No one’s forcing me to make this recording, Patricia insists. A brief click, the lisping of a tape being rewound, “… understand that I am a, uh, symbolic example and a symbolic warning not only for you but for all the others.”

When you find yourself with Violaine in the kitchen, you sip your tea without a word, no mea culpa and Violaine doesn’t dare bring up again Patricia’s expression that she therefore in fact completely understood, nor ask you who these others are, “all the others,” does she mean “warning” in the sense of an alarm or of a threat, of what is she supposed to be the example, Patricia…?

You’re expected in San Francisco December 15. There, like the other expert witnesses, you’ll be briefed on the potential attacks from the judge and the prosecutor on your credibility and your past. We’ll turn your revolutionary experience into an asset, the lawyer promises. Who could be better placed than you to know that, in these groups, you don’t find many 19-year-old heiresses who’ve never participated in a demonstration? That a lawyer whose universe is limited to Harvard and the circle of influential Republicans would harbor this type of certitude is hardly surprising. That you’ve shown yourself so sure to be able to prove him right is more intriguing.

But here at your side sits a skinny French teenager. Why listen to Patricia at all if you’re going to refuse to hear her?, she innocently asks you over and over. Her question, you also can’t allow yourself to hear it, you whose job is to prove that Patricia doesn’t know what she’s saying. You were right the day you hired her, Violaine understands perfectly well what you’ve given her to read, just not in the way you need.

Day 15

Are you eviscerated by an experiment which is not turning out the way you wanted it to, all these discussions in which Violaine continues to whittle away at your attempts to prove that Patricia Hearst was brainwashed? Are you drained, between teaching every other day and writing the report, are you pre-occupied by the prison sentence in store for Patricia if the Defense shows itself incapable of proving her innocence — or worried about seeing your reputation tarnished, you who up until now have lived a dream life, the trial promises to be extremely mediatized, your defeat will be public, Neveva Gene couldn’t be bothered to come up with three measly lines to save Hearst. On this particular morning you usher Violaine in and swing open the door to your bedroom to reveal, carefully spread out across the carpet, a mosaic of Patricias. Ten tableaux, the magazine covers from Time and Newsweek. Ten attempts to forge a coherent portrait. One melting into the other, the covers overlapping and supplanting each other.

The cover from February 6, 1974, “SHATTERED INNOCENCE,” a Patricia bearing a wide grin, under the tender blue of a fixed horizon, her hair tossed and tussled by an ocean breeze, she’s wearing a boy’s striped Polo shirt. The cover from February 13, “WHEN WILL SHE BE SET FREE?,” with a pensive Patricia coiled up in a vast green armchair, her father with his back against the bookshelves standing behind her, his hand resting on her shoulder. The cover from March 10, “FIANCÉ TALKS ABOUT PATRICIA.”

Violaine sinks to her knees, careful not to move the photos. Here’s the most recent one, you indicate the Time cover from April 4, 1974. No more blue, no more sky, but fire. The background of the image is red,**** like the fire of a nightmare which announces the color, red like the flag of the SLA in front of which she poses, her legs slightly apart, Patricia is 20 years and one month old, she wears a beret slanted back over her undulating auburn hair, the leather bandolier of an M16 rifle rumpling the khaki fabric of her blouse. A wide black banner splits the image of the heiress in half: GUILTY.

You tell a stunned Violaine that what you’re going to listen to now is a bit shocking. The discourse itself but also Patricia’s tone, the way she talks to her parents. You propose to listen to the recording three times, once with the eyes closed, to take notes, and then to rapidly read the dailies from April 1974. Only afterwards will you talk about them.

Tape 4, broadcast April 3, 1974

“I’d like to start out by emphasizing that what I’m about to say I wrote on my own. This is how I feel. No one’s ever forced me to say anything in these messages. I haven’t been brainwashed, or drugged, or tortured, or hypnotized. Mom, Dad, I want to start off with your pseudo-efforts to ensure my safety. Your gifts were an act. You tried to fool people. You screwed around, played for time, all of which the FBI used to try to kill me and the members of the SLA. You pretended you were doing everything in your power to get me freed. Your betrayals taught me a lot and in that sense, I thank you. I’ve changed; I’ve grown up. I’ve become aware of many things and I can never go back to the life I lead before; that sounds hard, but on the contrary, I’ve learned what unconditional love is, for those who surround me, the love that comes from the conviction that no one will be free as long as we’re not all free. I’ve learned that the dominant class won’t retreat before anything to extend its power over others, even if this means sacrificing one of its own. It should be obvious that people who don’t give a hoot about their own child don’t care anything about the children of others.

“I’ve been given the choice between: 1) being released in a safe place or 2) joining the SLA and fighting for my own liberty and for the liberty of all the oppressed. I’ve decided to stay and fight. No one should have to humiliate themselves to line up for food, nor live in constant fear for their lives and those of their children. Dad, you say that you’re worried about me and for the lives of the oppressed of this country, but you’re lying and, as a member of the ruling class, I know that your interests and those of Mom have never served the interests of the people. You’ve said that you’ll offer more jobs, but why don’t you warn people about what’s going to happen to them, huh? Soon their jobs will be taken away. Of course you’ll say that you don’t know what I’m talking about, you’re just a liar, a sell-out. But go ahead, tell them, the poor and oppressed of this country, what the government’s getting ready to do. Tell the Blacks and the vulnerable that they’ll be killed down to the last man, women and children included. If you have so much empathy for the People, tell them what the energy crisis really is, tell them that it’s just a clever strategy to hide the real intentions of Big Business. Tell them that the oil crisis is nothing more than a way to make them accept the construction of nuclear power plants all over the country; tell the People that the government is getting ready to automate all the industries and that soon, oh, in five years at the most, we won’t have need of anything but push-buttons. Tell them, Dad, that the vulnerable and a big part of the Middle Class, they’ll all be on unemployment in less than three years and then the elimination of the useless will begin. Tell the People the truth. That the maintaining of order and the laws are just an excuse to get rid of the supposedly violent elements, me, I prefer being lucid and conscious. I should have known that you, like other businessmen, you’re perfectly capable of doing this to millions of people to hold on to power, you’d be ready to kill me for the same reasons. How long will it take for the Whites of this country to realize that what’s being done to Black children will sooner or later happen to White children?

My name has been changed to Tania, in homage to a comrade of the struggle who fought with Che in Bolivia. I embrace this name with determination, I’ll continue her fight. There’s no such thing as partial victory. I know that Tania dedicated her life to others. To fight, to devote oneself entirely in an intense desire to learn…. It’s in the spirit of Tania that I say, Patria o muerte, venceromos.“

From pages 139-140:

(The “I” in this segment is the narrator herself, now an adult after having in her turn grown up at the knees of the adult Violaine.)

I’m 37 years old, we’re in 2015, young women are vanishing from their homes. They’re signaled at the borders, designated “S” (likely to commit terrorist acts), inscribed in organizational charts, with graphics establishing the co-relations between them: Coming from the Middle Class for the most part, they range from 15 to 25 years old, and displayed no signs in the preceding months of what was to come. The parents didn’t see it coming when they discovered, stupefied, the B-sides of their children on the ‘Net, in video messages they ask accusingly, in monotone voices, How can we claim to be humanists when in the face of injustice we remain immobile, are we not guilty, with our indifference to the poor? Let’s admit it and say it out loud, they’re a warning. For hours and hours I watch the reportages, read and cut out the articles for no reason, without any particular end, pages and pages of questions, why these girls, to whom everything was permitted and who now grace the magazine covers, they stare at the camera, an arm flattening out their breasts dissimulated under a jumble of fabric. I send the articles to Violaine, the declarations of adults panicked by these impenetrable young girls and who propose to ‘reprogram’ them in a few weeks. Violaine is initially skeptical, Patricia didn’t want to kill anyone, the SLA’s credo was humanist even if it failed, be careful about over-simplifications. We pick up our abandoned discussions, these editorials, 40 years later, employ the same words as in 1975, Could they be our daughters, our sisters, our friends? Violaine answers with a short phrase copied onto a visiting card: “What some people call ‘conversion’ or see as a sudden change isn’t one but a slow process of development, a bit like that of photographs, you know.” — Patricia Hearst (Tania)

Fashionistas, 2: Impressionism, Fashion, & Modernity at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Ignore the conceit, go for the paintings

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “The Millinery Shop,” ca. 1882-86. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 43 5/8 in. (100 x 110.7 cm). the Art Institute of Chicago. Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Text copyright 2013, 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

First published on our sister magazine the Arts Voyager on February 12, 2013, today’s re-posting of this story and the above related piece is dedicated to F.I., M.C., and V.S. in sincere appreciation of a stimulating evening et moment de partage and in the spirit of our continuing search for inter-cultural understanding. Like what you’re reading? Please let us know by making a donation today. Just designate your payment through PayPal to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. No amount is too small. To translate this article into French or another language, please use the translation engine button at the right of this page.

If context illuminates in Cezanne and the Past, on view at the Budapest Fine Art Museum through February 17, for Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art February 26 and running through May 26, it threatens to obscure (at least if one is to judge by the press release). Co-curated by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Musée d’Orsay, the exhibition’s thematic presentation seems to super-impose a subject-driven mode of operation which was never the Impressionists’ primary concern. Subject was important only insofar as it provided a prism for light and a means to experiment with other technical elements like volume and color values. If sentiment (Cézanne and Morisot) and social concerns (Pissarro) often also figured into the mix, and if it’s true that some revolutionized the art and bucked public and critical ridicule when they introduced modernity (Manet and Cézanne again), and many more incorporated new sciences like photography (Degas and the Nabis), the Impressionists were not so concerned with following “the latest trends in fashion” (as the Met’s PR puts it). So unlike Cezanne and the Past, where the artist’s career-long revisiting of his predecessors is well-documented, the primary impetus here seems to be marketing. That said, if you can set aside the feeble premise, the exhibition (which promises 80 paintings and supplementary material) is still worth seeing for the way it follows first and second-tier (notably Caillebotte, who was also an influential collector) Impressionist painters and their contemporaries (Fantin-Latour’s portrait of Manet is a revelation; Tissot here rivals Monet in color vibrancy) into corners of 19th-century Parisian life where we don’t usually see them: Degas takes a busman’s holiday from painting nudes to visit a millenary, and from sketching the ‘petites rats’ of the Paris Opera school to capture the august stockbrokers of the Bourse; Caillebotte then follows them to one of their plushy clubs, perhaps on the rue Victoire. In other words, if you can ignore the sexy (if tired) conceptual premise, you still might be seduced.

For additional commentary, please see the captions below.

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection.

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection.

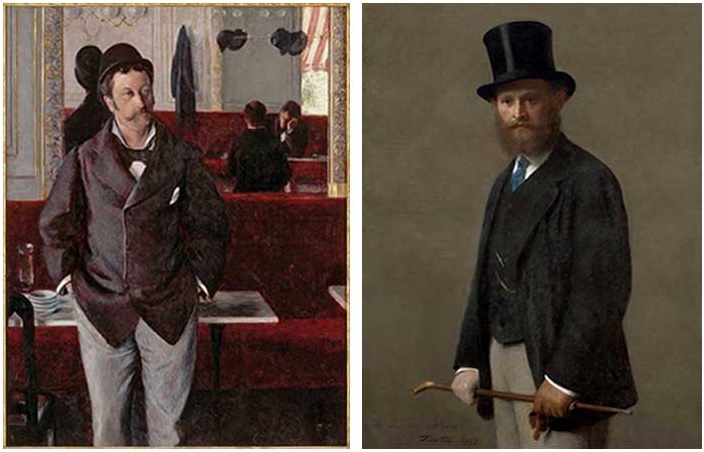

Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.)

Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.)

Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart.

Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart.

Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry.

Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry.

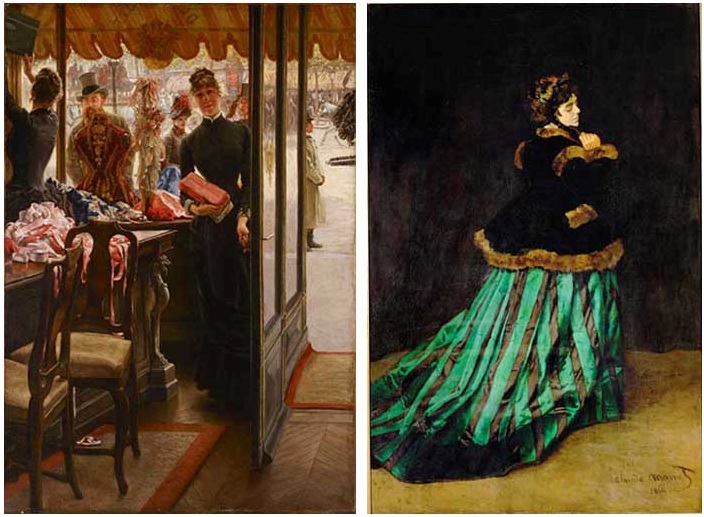

Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen.

Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen.

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color.

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color.

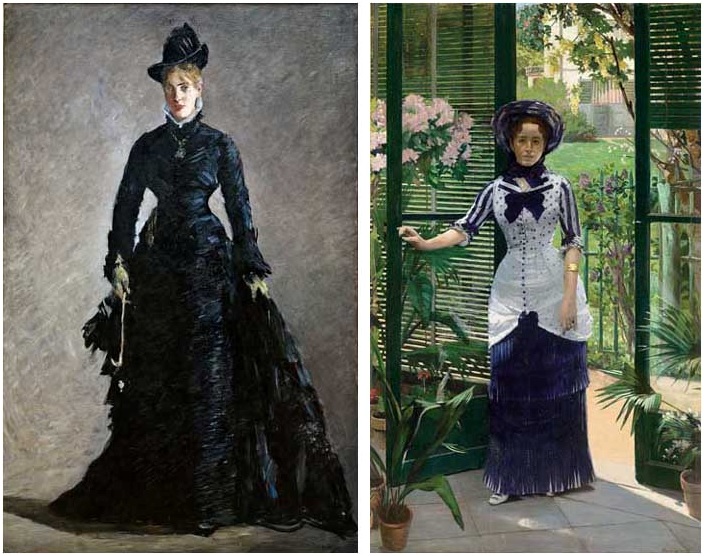

Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

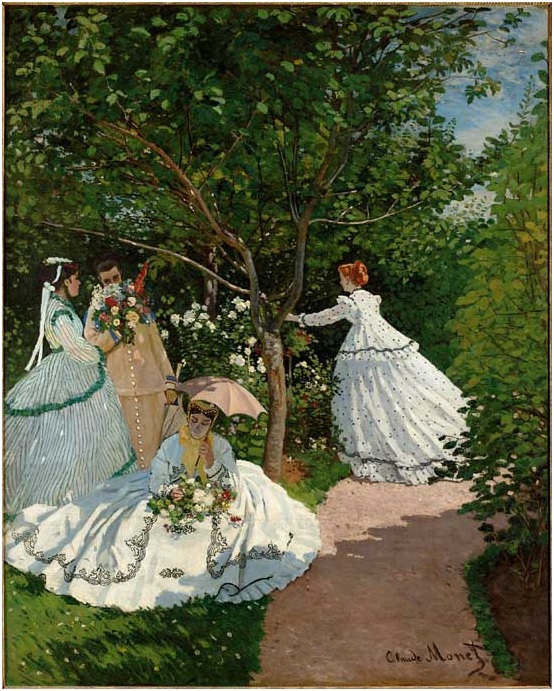

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Women in the Garden,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 100 3/8 x 80 11/16 in. (255 x 205 cm) Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

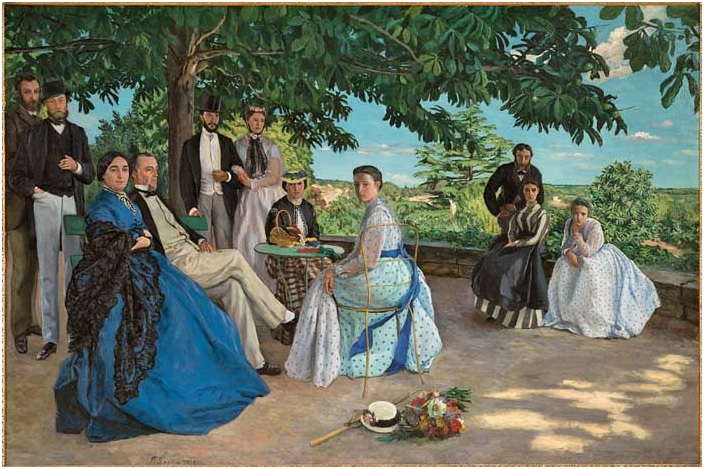

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone.

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.

What Abstract-Figurative War? In Saint-Germain de Pres, the Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger explodes the notion of the Great Divide

In an age when so many contemporary artists, whether in Paris or New York, seem to be simply re-inventing the wheel, what we at The Paris Tribune love about the Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger is that it’s found a way to bridge the work of the pioneers many of whom it was the first to champion — Dubuffet, Staël, Vieira da Silva — with living artists perpetuating that investigation in 2019. And to probe the complex relationship between the abstract and figurative movements that is more complex than many critics would have you believe. You can catch the current manifestation of this aesthetic dexterity — on the part of both the artists it represents and the gallery’s curators — in the exhibition Youla Chapoval, running at the gallery’s Saint-Germain des Pres space in Paris through March 2. Above: Youla Chapoval, “Polaire,” 1950. Courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger.

Paris to Villeneuve-sur-Lot: How the Southwest was won by a gallerist in Saint-Germain des Pres

Jean Dubuffet, “Site domestique (au fusil espadon) avec tete d’Inca et petit fauteuil a droite,” 1966. Vinyl on canvas, 125 x 200 cm. Fascicule XXI des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, ill. 217. Copyright Dubuffet and courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

Jean Dubuffet, “Site domestique (au fusil espadon) avec tete d’Inca et petit fauteuil a droite,” 1966. Vinyl on canvas, 125 x 200 cm. Fascicule XXI des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, ill. 217. Copyright Dubuffet and courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Text copyright 2014, 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

First published on the Paris Tribune’s sister magazine Art Investment News on September 14, 2014. (Like what you’re reading? Please let us know by making a donation today. Just designate your payment through PayPal to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. No amount is too small. To translate this article into French or another language, please use the translation engine button at the right of this page.)

PARIS — Accessibility has become a dirty word, with its implication that to reach the masses, art must be dumbed down. But truncate the word to “access,” and you understand the collaboration that the municipality of Villeneuve-sur-Lot in Southwestern France — a region better known for the fertility of its grapevines than the fecundity of its modern art scene — and the legendary Saint-Germain des Pres gallerist Jean-Francois Jaeger of the Gallery Jeanne Bucher Jaeger have forged over the past 45 years, under which the anything but hic residents of this ‘provincial’ town have been able to experience the contemporary art revolution(s) of the ’50s, ’60s, and beyond contemporaneously with the putatively hip Parisian public. This complicity is being celebrated, through October 26, at the Musee de Gajac, a converted Villeneuve flour mill, in “A Passion for Art: Jean-Francois Jaeger and the Gallery Jeanne-Bucher Jaeger,” with work selected by the 90-year-old honoree which, true to form, prizes mystery over mediocrity and discovery over dilettantism.

If the Gallery Jeanne-Bucher has fulfilled the central mission of a contemporary art gallery for nearly 90 years, as an avatar (or avant-garde for the avant-garde) for Cubism (exhibiting Braque, Picasso, Gris…), Abstraction (Kandinsky, Mondrian, Klee, Arp…), and Surrealism (De Chirico, Ernst, Giacometti, Masson, Miro, Tanguy, Picabia…), Jeanne Bucher was not looking to attract solely the Parisian and international cognizanti to her gallery on the rue de Cherche-Midi (later on the boulevard Montparnasse and eventually the rue de Seine) when she founded it in 1925, but to “diffuse the taste for art amongst all classes.” Jaeger, who took over direction of the gallery in 1947 (officially succeeded in 2003 by his daughter Veronique), has implemented that mission with aplomb by loaning or arranging the loans or gifts of contemporary art to the Gajac Museum and its predecessor institutions in Villeneuve and its environs, notably for two biennales and four major exhibitions since 1969, dedicated variously to Roger Bissiere and Friends (the friends including Andre Lhote and Georges Braque); Hans Reichel; artists of Algeria and the South; and Spanish artists persecuted by Franco, many of whom found refuge in Southwestern France. Bissiere, a native of the region, is accorded a central place in the oeuvres selected by Jaeger (given carte blanche by the museum, an indication of the trust he’s earned with the community) for this latest exhibition, accompanied by major examples from Jean Dubuffet, Vieira da Silva, Louise Nevelson, Fabienne Verdier, Hans Reichel, Mark Tobey, Nicholas de Stael, Fermin Aguayo, Yang Jiechang, Jean Amado, and Susumu Shingu, the ensemble promising “que d’aventuresoffered to our curiosity, to our search for a real initiation,” as Jaeger puts it. He goes on to praise the Gajac museum as “one of our best provincial museums.” When most Parisians use the term ‘provincial,’ they mean it as an insult, but Jaeger is speaking strictly geographically; there’s nothing provincial about the Gajac programming, which seems more interested in “initiating” its public in major 20th- and 21st-century artistic currents than providing fleeting encounters with random works or catering to existing tastes with sure box-office hits. By comparison, it’s the major exhibitions in Paris and New York this summer that have seemed provincial, with the Petite Palais re-visiting (encore?!) “Paris 1900,” the Pompidou the relationship between Breton and Picabia, the Orsay Van Gogh (albeit as analyzed by Artaud), and New York’s Museum of Modern Art the Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec.

Nicolas de Staël, “Jour de Fete,” 1949. Oil on canvas, 100 x 73 cm. No. 176 of Catalogue Raisonne. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

What unites most of the work on display in Villeneuve-sur-Lot is not just that it favors the abstract over the figurative, but that this is abstract art whose complexity invites the viewer to engage. This kind of engagement doesn’t happen overnight. Like the dark malbec-based Cahors wine in the county of the Lot which neighbors Villeneuve-sur-Lot, it’s the fruit of years of cultivation. And indeed, it was more than 50 years ago that the artistic brain trust of Villeneuve-sur-Lot started planting the seeds of artistic appreciation in its community. (The other factor that unites most of the artists in this exhibition, is that — with the exceptions of Dubuffet and de Stael, who can be seen as the elders of the epoch — most are part of a generation of artists who flowered from the late ’40s to late ’60s, a lost generation in the institutional memories of most big-city museums.)

In 1963, as Jacques Balmont, a printer by trade, recounts to Emmanuel Jaeger in the presse dossier for the exhibition, Balmont got together with Rene Verdier, local salon organizer Maurice Fabre, municipal art school founder and painter Pierre Raffi, and bookseller Robert Bonhomme to organize an annual exhibition open to both professionals and amateurs. After successive shows on provincial painters in 1964 and ’65, this informal committee increased the ante in 1966 with an exhibition devoted to the fauve (and Bordelaise) artist Albert Marquet — signaling that they understood something even schooled curators seem to forget, that a museum has a responsibility to rescue significant artists from the ‘oublie.’ (When I meet otherwise cultured young and not-so-young people — even artists — who don’t know who Suzanne Valadon, Berthe Morisot, Marie Laurencin, and Leonor Fini are, I assign their ignorance to the irresponsibility of the museum directors and curators whose sexism has excluded these major artists.) This interest by the local artistic brain trust in highlighting the ‘second tiere’ (not to be confused with ‘also ran’) of major mid-20th century movements continued in 1967 with a biennale featuring 48 works by another Bordeaux-born artist, Andre Lhote, culled principally from Lhote’s widow. But they didn’t stop there; the biennale also included work by Clave, Pignon, Chastel, Louttre-B and 150 provincial painters.

Roger Bissiere, “Vert et Ochre,” 1954. Oil on jute canvas, mounted on contreplaque. Courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

For the next biennale in 1969, it was time for Balmont and associates to finally combine their fidelity to local talent with their curiosity about under-represented international-caliber artists, and for this one figure presented himself: the recently deceased Roger Bissiere, a master of post-War abstraction born in nearby Villereal. Enter Jean-Francois Jaeger.

When the Villeneauve team sought out Bissiere’s son, he told them that they absolutely needed to enroll Saint-Germain des Pres gallerist Jaeger and the Jeanne-Bucher Gallery, which had represented Bissiere since 1951. They would have been happy with enough tableaux for an exhibition focused solely on Bissiere, but Jaeger — in a pattern that would repeat itself over the next 45 years — was thinking bigger. He proposed instead to expand the event under the rubrique “Bissiere and Friends.” “And what friends!” recalls Balmont. In addition to 67 paintings, three tapestries, and 10 lithographs by Bissiere, the exhibition at the Theatre Georges-Leygues included work by Braque, Lhote, Vieira da Silva, and Hans Reichel. This in turn ‘enchaine’ed into a fourth biennale in 1971 consecrated principally to Reichel, a disciple of Bauhaus and compagnon de route of Paul Klee, Lawrence Durrell, Henry Miller, and Anais Nin. The nexus was once again Jaeger who, from the collection of the Jeanne-Bucher Gallery, Reichel’s companion, and private holdings secured 75 watercolors and paintings dating from 1921 to 1958. This grandeur of vision — augmented by a complementary exhibition of other artists — contrasted comically with the seat of the pants logistics, which saw Balmont and his colleagues transporting large-scale works by Hans Hartung, Serge Poliakoff, and others from Paris to the south with municipal trucks typically reserved for filling pot-holes.

The heart of any museum is its permanent collections, which serve both as a pedagogic reference and a potential treasure chest for future acquisitions. Perhaps impressed by the community’s seriousness in establishing an acquisition fund in 1976, Jaeger next convinced Louttre-B, Bissiere’s son, to make the Musee Rapin, Gajac’s predecessor museum, the depository for his 220 existing engravings and any to come.

Unfortunately, the downside of government investment in the arts is that it leaves the arts vulnerable to changes of personnel and policy (curators propose, politicians dispose….). (That the legendary French singer-songwriter Charles Trenet is its most famous export didn’t stop the new mayor of the Languedoc town of Narbonne from de-funding and effectively canceling this year’s edition of the prestigious Trenet festival. And while Villeneuve’s current mayor proudly proclaims the town’s policy of making culture “accessible to all,” Alain Juppe, mayor of the regional capital of Bordeaux, former prime minister, foreign minister, and presidential candidate, recently revealed himself as a small thinker when it comes to the arts by eliminating free access to the permanent collections of the municipal museums.) Thus it was that Jaeger’s subsequent enlistment of Francis Mathey, who as chief conservateur of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris had introduced Dubuffet, Balthus, Yves Klein, Pierre Soulages and a generation of young artists in France (“One of my mentors,” Jaeger says, “the first to open his museum to living artists never before exhibited in France”) in Villeneuve’s artistic future went for naught after a new government elected in 1977 lost interest in the project. It took 25 years and another change at city hall for a planned museum of art and history of the Valley of the Lot in a renovated ancient mill to be re-oriented into a museum of beaux-arts. Once again, indigenous resources and the global view of Jaeger combined in 2003 for the (re) inaugural exhibition, “Mere Algere, couleurs de Sud,” whose fount was several works donated by Maria Manton, part of the brain trust of previous exhibitions and a major Algerian-born artist. Next came “L’action pensive” in 2007, built around post-war giants of Abstraction like Nicholas de Stael, Poliakoff, Bissiere, Vieira da Silva, and Louis Nollard, followed in 2008 by “La representation pensive,” dedicated to figurative artists of the same epoch, with oeuvres lent by the Centre Georges Pompidou, the Museum of Modern Art of the city of Paris, and the Fondation Dubuffet. The ante was upped even further in 2010. Inspired by commemorations of the 80th anniversary of the Spanish Civil War, and cognizant of the region’s role in welcoming exiles of the Franco regime, Jaeger and crew programmed “Spain, the dark years,” convincing leading French and Spanish museums to loan work by Miro, Julio Gonzalez, Fermin Aguayo, and even Picasso’s tapisserie for “Guernica.”

In the press dossier for “A Passion for Art: Jean-Francois Jaeger and the Jeanne-Bucher Gallery,” Emmanuel Jaeger, noting the evident complicity between Balmont and Jaeger, asks the former whether there’s any single element linking Villeneuve and the gallery.

“It was after ‘Bissiere and his Friends’ and ‘Hans Reichel’ that a friendship was really born between us,” Balmont recounts. “Every time I go to Paris, my route takes me immediately to the rue de Seine, to see Jean-Francois. Our conversations have enriched me as privileged moments of discovery and knowledge…. Besides the links of friendship, of a cultural connivance, I think that Jean-Francois was drawn to our little provincial town which made the choice early on to expose its citizens to the art of its time. The will of the Gajac Museum to initiate, to democratize modern and contemporary art corroborate perfectly the fabulous trajectory of Jean-Francois and the Gallery Jaeger-Bucher/Jeanne-Bucher.” And for Jaeger, “Every return to the country of Bissiere procures for me an intense emotion and vivid sentiment of recognition for he who taught me everything when I was just beginning.” Not that the education ever stopped. “It’s in the contact with artists, and the example of their own permanent curiosity, that we have been able to refine our knowledge, not in the history of art but in its practice, in the service of those on whom destiny had conferred special gifts,” says Jaeger. “Those who make history do not constantly refer to the past, but listen to what a creator’s temperament can bring them to discover in themselves.”

Trolling the galleries around Saint-Germain des Pres on a late July afternoon, starting out on the rue de Seine, I wandered into a deserted courtyard at the base of which was an unobtrusive gallery. With no glitz and nary a mis-en-scene, the four walls sported treasures by Bissiere and Vieira da Silva, among others, which expressed not only their authors’ visions but the zeitgeist of a whole artistic era. A young woman dressed in black was occupied scribbling notes behind her desk. From a desk near hers, a dapper man dressed in a drab brown suit, tan slacks, and dark loafers murmured something before slowly rising to take the air outside the gallery. No glamour. No glad-handling. (And no other visitors in the gallery besides me.) And yet this was the man who, with no fanfare, has for nearly 70 years quietly created a home for contemporary artists typically ignored (until they’re dead anyway) by the major museums (Dubuffet was for years excluded by the Pompidou) not only in the heart of artistic Paris but, in a France perpetually obsessed with ‘decentralization’ (it even has its own ministry) in France profund. In a milieu more and more dominated by art dealers, Jean-Francois Jaeger is an art promulgator, ensuring that art doesn’t remain the province of the privileged but privileges the provinces.

Back to Africa: Cubism at Beaubourg

Among the more than 300 works on view through February 25 at the Centre Pompidou for its exhibition Cubism is, above, “Masque krou,” Côte d’Ivoire, undated and uncredited. (The museum actually credits the work to “anonymous,” but of course the artist had a name.) Painted wood, metal, and cork. 25.5 x 16.5 x 18.3 cm. Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon, Lyon. © Lyon MBA – Photo Alain Basset.

Among the more than 300 works on view through February 25 at the Centre Pompidou for its exhibition Cubism is, above, “Masque krou,” Côte d’Ivoire, undated and uncredited. (The museum actually credits the work to “anonymous,” but of course the artist had a name.) Painted wood, metal, and cork. 25.5 x 16.5 x 18.3 cm. Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon, Lyon. © Lyon MBA – Photo Alain Basset.

Art is art is art: When Picasso does Stein, there’s some there there

Among the 300+ oeuvres featured in the exhibition “Cubisme,” running at the Centre Pompidou in Paris through February 25 is, above, Pablo Picasso, “Portrait of Gertrude Stein,” 1905-1906. Oil on canvas, 100 x 81.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist RMN-Grand Palais / image MMA. © Succession Picasso 2018.