by Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2021 Paul Ben-Itzak

First, I guess I should explain — before the libel suit rolls in — that the manner of speech employed in the headline, far from making serious aspersions on the moral character of the journalist in question, is a tongue-in-cheek homage to the old Saturday Night Live take-off on the old 60 Minutes (note to French audience: American news show) segment “Point – Counterpoint,” in which pundits putatively positioned on the Right and Left faced off over topical societal questions. In the SNL spoof, a cardboard caricature of conservative columnist James Kirkpatrick, often paired off against liberal Shana Alexander, finally expectorates, “Shana you ignorant slut.” The most brilliant gladiator in the real version was Nicholas von Hoffman, a columnist with Left leanings who my ninth grade buddy Max Yarowsky turned me on to. (Max graduated to become a women’s health care provider, which probably explains why I can’t find his contact information on the Internet, given the bounty put on the heads of abortion providers by some extremists in recent years.)

Here in France, there’s a neo-conservative pundit — a member of the Academy Francaise, no less (and he’s no Anatole France in my view) — who would pretend to offer a sort of Gallic version of Point – Counterpoint, “Replique,” a weekly soapbox on the middle-brow Radio France chain France Culture. “Soapbox” because while he often features real debate, Alain Finkielkraut conveniently waited until the previous New York Times Paris correspondent had left town to criticize his position on what he sees as the position of Muslims in France, concluding by praising the Times’s decision to (in his view) “repair the damage” by replacing him with Roger Cohen.

While I haven’t yet had the pleasure to be edified by Cohen’s position — excuse me, reporting, as Cohen claims to have moved back from having a rubric to the ‘news side’ — on Muslims in France, he made a snide comment Saturday morning on one aspect of the platform of one of the two finalists facing off this week-end in the Green Party primary run-off for April’s presidential election that makes it clear that he has absolutely no understanding of the French social model, nor of how the United States could stand to learn a lesson from it. Roger, as polemicists go, you’re not fit to carry Nick von Hoffman’s jock.

Supposedly opining on the place of the ecology in politics — one of the two topics of Caroline Broué’s weekly France Culture discussion with Paris-based foreign correspondents theoretically covering events in France — Cohen criticized, in that patented Times manner which manages to be both snide and cluelessly completely out of touch at the same time — Sandrine Rousseau’s proposal for a minimum revenue of subsistence, identified by Cohen as being around 850 Euros per month. “Getting paid to stay at home and do nothing, that’s not too shabby,” Cohen derisively joked. (I’m translating; sounds more haughty in Cohen’s French. And while we’re in a parenthesis: You try to subsist on 850 Euros per month, Roger. More on that further down.)

Let me tell you, Roger, what being a foreign correspondent — what being a reporter — means.

Being a foreign correspondent means interpreting and explaining the society you’re covering to the audience back home, in this case for an American audience. Obviously and inevitably, the foreign correspondent is looking at the covered (foreign) society’s mores through his or her own native perspective — which is, after all, that of your (to mix my pronouns) readers. But you still need to have the ability, the knack, or at the very least the inclination to get inside the motor of the covered country (and its citizens) and understand and explain what makes it tick, ideally in a manner that portrays the big picture by sketching a detail.

Let me give you, Roger, an example from my own experience, that of someone who has covered France for 21 years, prior to that covering New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut for an international audience for my own magazines and other publications, including yours, and prior to that covering San Francisco for Reuters. (Which is not to vaunt my own experience, alacrity, reporting skills, or even ability to clearly understand, interpret, and explain a foreign phenomenon to my American readers, but rather to demonstrate that I at least attempt to understand the foreign subject from its own perspective, even if my own Native biases — particularly on the subjects of lay-ism and racism — are sometimes hard to surpass…, and in this one specific case captured the element which might most appeal to my readers.)

In France, freelance performance artists and technicians have their own unemployment status, the Intermittents Regime. To simplify (and my exact numbers might be off, as these are regularly adjusted), artists and technicians who clock about 500 hours over about 10 or 10.5 months in a given year are eligible for unemployment benefits the following year — no matter how many different employers they clock those hours with. I learned and wrote about this special regime in 2003, when threatened changes — as I recall, a slight increase in the number of hours required and a reduction to eight of the number of months one had to log them — provoked national demonstrations by the Intermittents, as well as performance and summer festival cancellations. (For the Covid period — which involved confinement and theater suspensions, and thus put most Intermittents out of work — the government has accorded “white years,” meaning that the requirement to log the hours in one year to qualify for benefits the next was waived.)

At the time, the core of our audience for the Dance Insider magazine was American and other “pick-up” dancers, so-called because they work for a variety of companies; in the States (unlike France, where besides the national ballet companies, at least 22 companies are awarded regional choreography centers), only a handful of Modern Dance companies can afford to pay their dancers full-time salaries. The rest of the companies — and thus the rest of the dancers — work for a variety of companies, which work, when they’re out of work, does not qualify them for unemployment benefits. In the States, at least the last time I profited from the regular unemployment benefits regime, you had to have worked at least one year for only one company, full-time, and have been fired, not quit, to qualify for six months of unemployment compensation which topped out in 1998, at $300 per week. (For the Covid period, even independent contractors received about $2,600, regardless of hours worked, if they fell below a certain poverty threshold). (And no, Roger, I didn’t use my unemployment benefits in 1998 to stay at home and do nothing; I used them to re-launch a free-lance career, including writing for your newspaper and ultimately to co-found the Dance Insider when I realized that newspapers like yours, for which I covered the arts as a freelancer, were not interested in stories that I and my dancer co-founders knew were stories.)

In other words, pick-up dancers in the U.S. need to have other day jobs to survive, and work their dance jobs on top of that. (The choreographers sometimes can’t even afford to pay them for rehearsal hours.) They cannot add together the hours they’ve logged for various companies — even if cumulatively these hours amount to full-time. This has real creative consequences for the choreographer-directors of smaller (most) companies, particularly if their language is unique, because it takes time to teach dancers that language, to develop a corps of performers who speak it. Most of the choreographers, like the dancers, eventually burn out and end up returning to or teaching at schools (which jobs they may be quite invested in).

In France, by contrast, performance artists and technicians who work at least 507 hours per year, even if it’s for multiple companies, can afford to just do that work… which not only lets them concentrate on their art (to the benefit of the arts-going public, at least when they can produce transcendent, relevant work) but in turn contributes to the creativity of the choreographers, sustains the theaters (which employ the technicians), and directors, thus contributing to the French cultural exception. (Something which even you, Roger, may have heard of.)

I have known a few Intermittents, and let me tell you, Roger, they are anything but slackers. My last roommate was an Intermittent, and she worked more than full-time, lived in a potential fire-trap, needed to have roommates to split the relatively low rent (still above 850 Euros) on her 37-square meter apartment (in a Paris suburb where you, Roger, have probably never set foot) and, the last time I saw her, still needed to take food hand-outs from a social service agency.

But to get back to the role of a foreign correspondent, and how my understanding of and reporting on the French Intermittents regime for my mostly American audience both did justice to the foreign population covered and edified my Native (U.S.) reader constituency, and what this example reveals about why Roger Cohen felt the need to, in contrast to me, denigrate a potential new evolution of the French social safety net completely in line with this tradition.

For the population (and country) covered, besides illuminating a concrete example in the cultural domaine which presented a better model of the way things might be to my American audience, I was trying to point to a broader and fundamental, society-wide and defining characteristic of a country through a detail. (There’s a term for this, and it may be super-annuation.) In France this is called the French social model — a model that, in the minds of some, has been at risk here for the past decade.

One proposition that has been put forth by presidential candidates on the solid Left since at least the last election, in 2017 is a “revenue of subsistence.” Contrary to Roger Cohen’s snide and intellectually lazy dismissive insinuations, this does not mean you get paid to stay at home and do nothing. Rather, it guarantees a modest revenue to help ensure you and your children won’t find yourselves homeless and hungry. In Paris these days — or rather outside of Paris — if you’re lucky and get there first, 850 Euros might get you a 27 square meter apartment with a minimal kitchen. In Paris, it’s more likely — and particularly if you’re a student who doesn’t yet know your way around — that you’ll end up paying 900 Euros for a 20-square meter apartment. If you can’t get above 650, expect to live in a closet. (While we’re on housing, here’s another example of how just because they have their own regimes, the Intermittents don’t have it easy: In my own quest to return to Paris, I belong to a Facebook group, Intermittents Solidarité Logement, in which members who will be of town largely for work gigs seek to rent their pads, or even just seek roommates, to supplement their income. In other words, they need every penny that they can get, even if it means letting strangers into their homes ((sometimes with drastic results; one Intermittent described, on another France Culture show, how he’s been unable to get his subletters out)). I somehow doubt that when Roger goes back to New York for journalism refresher courses he lets out his pad in the 6eme, 7eme, or 16eme.)

In reality, the revenue of subsistence would likely consolidate various other social welfare supplementary assistance programs which already exist. (And, in case I haven’t made it clear, Roger: 850 Euros will neither house you comme il faut let alone feed you in a French city, even more now as gas costs have risen 10 percent, electricity costs also, and food prices are reported to go up. But of course you, Roger, are probably paid more than that by the NY Times. So the recipients will not be “sitting at home doing nothing,” as you snidely proclaimed. You try to get by on 850 Euros per month, Roger!)

In rural southwest France a few years ago, working the vendange or wine harvest in the Lot, I met a young woman, formerly homeless, living in a small gypsy wagon or roulette (she had a horse for whenever she needed to move on) she had built herself, in which her father had helped her install solar power. She bathed herself in a barrel outside, and used an external “dry toilet” without walls. (I used her old camper and another barrel and dry toilet a bit down the path; you should try taking a crap in a dry toilet without walls at 7 on a blustery fall morning Roger, it might enlighten you. Come to think of it, it was the young lady’s toilet, which she abdicated for me, fine for herself with just going in the woods.) She benefited from one of the existing social safety net programs designed for young people, which brought her — for a limited time — about 450 – 550 Euros per month… And even then, was subject to control by state officials to verify that she had a project. Helene worked hard all day — I at times worked beside her — preparing hearty meals for the vendangers. And leant her old camper, for free, to the winemaker so that he could house me and my cat. Besides this young woman and me, there were about 30 ‘vendangers’ who had driven in, at their own expense, from Brittany to harvest the grapes, in exchange for meals, housing, and a few bottles of organic wine. (And most of them were not as lucky as me — I was one of the cooks — but lived together in a dortoir. The winemaker’s Breton assistant slept in his daughter’s tree-house.) We started at 6h30 a.m., knocked off at about 7 p.m. or later, and worked 7/7 for three weeks. Our ages were from 18 to 75.

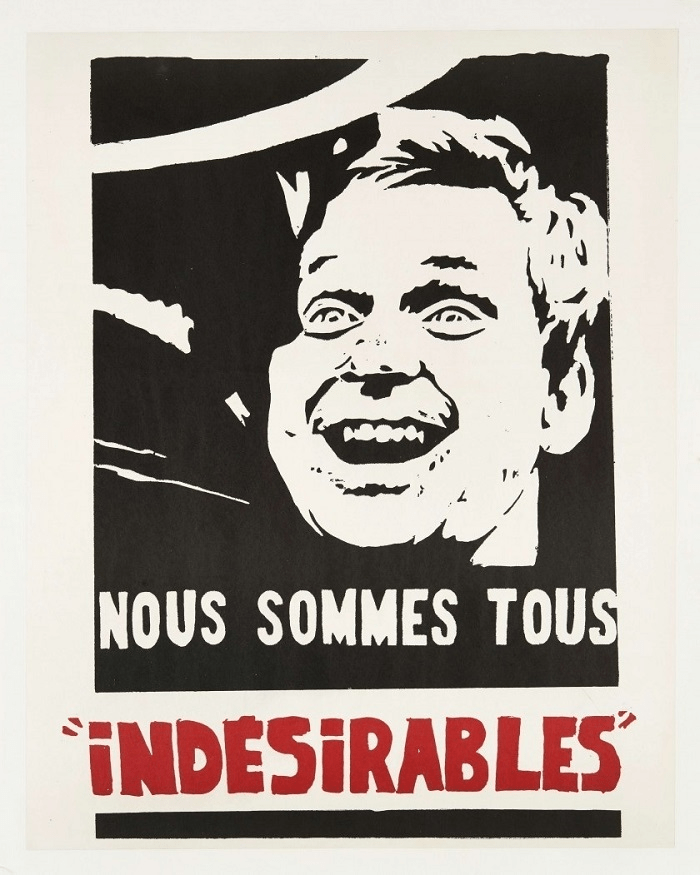

But to return to Roger, and the real reason he (or at least establishment institutions like the Times; Cohen has likely been doing it so long, it’s probably unconscious by this point) like to denigrate laudable social models (now threatened by Americanization) like those in Europe and France, of which Sandrine Rousseau’s proposal for a modest ‘revenue of subsistence’ — not a boondoggle like those the bankers in the U.S. received in the 2008 congressional bail-out, but a safety net — is not an aberration, but a natural outgrowth:

They are a threat.

They are a threat to an American capitalist social model in which (for example) my Princeton classmate Jeff Bezos, the owner of Amazon, is able to pay for his space junkets by imposing a production standard on his workers which does not even leave them time to go to the bathroom and engaging in Union-busting tactics when they try to organize.

Roger Cohen’s snide, denigrating, subjective, biased observation — an observation in which he failed in the fundamental, minimal function of a foreign correspondent, which is to understand, interpret, and explain the country he is covering and thus broaden the world of his readers at home, perhaps even giving them cause for reflection in seeing how another country handles similar issues they face (and giving them ideas!, Heaven forfend) — was, unfortunately, part of a long tradition of American red-baiting. (Which I myself have been a target of in the past; delivering the students’ response to draconian budget cuts following the Proposition 13 property tax reductions in California, in 1979, to the San Francisco School Board on which I was the student delegate, I was rewarded with an assistant school superintendent saying our point-by-point analysis of the disastrous effects the cuts would have on school programs “sounded like a Socialist document.” Tant mieux!) Which, given the current presidential politics in France in which Green Party candidate Sandrine Rousseau, if she’s chosen in this week-end’s primaries, may be the most viable standard-bearer of classically European social model standards, has devolved under Cohen into Green-baiting. (For more on the original to which this is the carbon copy, Roger Cohen might want to read I.F. Stone’s “The Haunted ’50s,” a copy of which I scored at a Left Bank bookstore for 1 Euro.) (Cohen was equally dismissive of the American Green party as ‘semi-embryonic,’ neglecting to point out that unlike the French system, the American two-party system effectively locks the Green or any other parties out of the presidential debates and thus pushes them under the mainstream corporate media radar.)

Simply put, Cohen and his establishment pay-masters are threatened, as they have always been, by the European social model; they are scared that their readers might want to emulate it. In this — grace of Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ingrid Thunberg, and others — they are already behind the times. Roger, of course you are not a slut. Mais vous-etes bien de-modé.

PS: Why should readers in the U.S. care what an American newspaper correspondent says on French radio? Given his dismissive — and in my view erroneous — voir derogatory comments on presidential candidate Sandrine Rousseau’s platform, it doesn’t bode well, notwithstanding Cohen’s statement that he has ‘gone over to the news side,’ for his Times readers getting a truly objective report — and thus learning about an idea applicable in the U.S. — on Rousseau’s ideas. All the news that’s fit to spit indeed (to cop a phrase from Bill Sokol).

Paul Ben-Itzak wrote for the New York Times from 1983 through 1998, and covered Princeton, Sacramento, and San Francisco for Reuters from 1982 through 1995 before co-founding the Dance Insider in 1998 in New York City. He has been covering France since 2000.