By Paul Ben-Itzak

Story (excluding citations from scenario for Camus exhibition) copyright 2012, 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

First published on our magazine Art Investment News in 2012. Albert Camus died 60 years ago today… in a banal traffic accident on his way back to Paris from Loumarin, where he’d been sojourning with his wife and children. On December 30, 1959, in his last letter to long-time soul-mate Maria Casarès, Camus wrote, in part : “See you soon, my superb one. I am so happy at the idea of seeing you again that I laugh in writing you. I have closed all my folders and stopped working (too much family and too many friends of family!). I therefore have no reason to deprive myself of your laughter, of our soirées, nor of my homeland. I embrace you, I clutch you firmly against me until Tuesday, when I recommence. — A.” To read our review of the recent publication of Camus’s correspondence with Maria Casarès, click here. Benjamin Stora is president of France’s Cité nationale de l’histoire de l’immigration in Paris.

Dans les actualités: Expo Albert Camus, “Albert Camus, l’étranger qui nous ressemble,” mis en scene et dirigé par Benjamin Stora et programmé pour Marseille-Provence capitale européenne de la culture, abandoné, re-programmé, et encore abandoné. (In the news: Expo Albert Camus, “Albert Camus, the stranger who resembles us,” conceived and directed by Benjamin Stora and programmed for Marseille – Provence Cultural Capital of Europe, abandoned, re-programmed, and abandoned again.)

“To reduce Camus to just one of (his) dimensions would make no sense. Novelist, playwright, essayist, journalist — Camus is all of these things at the same time. Each facet of his work nourished and shed light on all the others. We must thus mount a full life, a prolific oeuvre, which adapted different forms while conserving a remarkable coherence in its ensemble. Visitors will (discover) what unifies such a universe: A certain tone, at the same time joyous and disturbing, somber and resplendent with slivers of the Mediterranean sun.”

— Benjamin Stora, original commissar for the exposition “Albert Camus, l’étranger qui nous ressemble.”

“I do not believe, in that which concerns me, in isolated books. With certain writers, it seems that their works form an ensemble where each work is illuminated by the others, and where each regards the other.”

— Albert Camus, Complete Works, Volume III, p. 402 (cited by Benjamin Stora).

“Non, les braves gens n’ame pas qu’on suivre un route autre qu’eux.”*

— Georges Brassens

The occasion was as opportune as the disappointing denouement was perhaps inevitable, given the tendency of the interested to alienate people on both sides of any given question with a point of view and approach that often defied any fixed ideology, bred from the melanged influences of ideas and experience, intellect and instinct, reflection and urgency. At the heart of the Mediterranean capital Marseille’s campaign to win the European Union’s coveted and potentially lucrative Cultural Capital of Europe designation for 2013 would be the man who not only embodies everything that is heroic about France, a champion of philosophy, letters, the theater, even — as editor of the underground newspaper Combat — the Resistance to the German Occupation, but who better than anybody embodies in one man the intricate, still conflicted mosaic that is France’s relations with its former colonies, its own Mediterranean first man, Albert Camus. After all, wasn’t 2013 also the centennial of his birth? To organize the exhibition the Marseille – Provence committee promised to engage Benjamin Stora, a historian specializing in Algeria, French Algeria, and Algerian immigration in France, born in Algeria like Camus, the ethnic Frenchman who always considered himself Algerian, weaned on its terrain and nurtured by its brilliant Sun. Catherine Camus, Albert’s daughter and the guardian of his legacy and personal archives, approved Stora’s selection in 2010, as well as scenographie Stora proposed. The exhibition would take place not in gritty Marseille, that most Maghrebian of French cities, but in Aix-en-Provence (where most of Camus’s archives repose), Marseille’s once quaint, now touristic neighbor, ruled by Maryse Joissains-Masini, an arch conservative mayor who considers the town her fife (and who, when Francois Hollande was elected president, declared him “illegitmate”).

The scenario for the exhibition that Stora submitted with Jean-Baptiste Péretié, to be called “Albert Camus, the stranger who resembles us,” draws a portrait of the philosopher of action revealed in both his acts and words, never too lost in theoretics to ignore gnawing imperative, taking visitors on a parcours of his life arrayed in six rooms and connecting walkways evoking stages or places important to his route — the printer’s table, the stage, his office, a child’s room — and whose contents focus on Camus’s multiple lives and causes, including anti-Stalinism, opposition to the death penalty, the Resistance, and of course the Algerian war, the — if you will — existential struggle between the colonized thirsting for true independence, and the colonizer still convinced he is a not a jailer but a liberator, importing not oppression but civilization. What Stora envisioned was not a mere superficial promenade through the biography of a life, but, au contraire, to shatter the edifice Camus has become in French culture — a sort of matinee idol philosopher, the Humphrey Bogart of existentialism with cigarette dangling precariously at the end of his lips — and reveal the complex man beneath the sheen. Each room, and the walkways that connected them, would serve as an access point to the development and execution of Camus’s many combats, even those over which he was conflicted up to the moment of his death in January 1960 (in what a popular magazine of the epoch, Sonorama, called ‘a banal traffic accident’), such as Algeria.

Of necessity, because it was not a conflict about which he could be objective but one whose tensions were reflected in his own makeup, the struggle between France and Algeria became the ultimate playing field for his ideas and ideals. Indeed Camus, who loved soccer, must have felt at times like he was trying to reconcile two sides who could only see their own goal lines. Born in Constantine, Algeria, but working for decades in France and abroad, author of 30 books including “Gangrene and forgetfullness, the memory of the Algerian War (La Découverte, 1991)” and “Algeria, the invisible war” (Presses de Sciences Po, 2000), consultant and / or author of numerous films, documentaries, and programs on French television (including the upcoming film version of Camus’s last, unfinished novel, “The First Man,” which returns him to his childhood in Oran), Benjamin Stora seemed the ideal referee of the manifold Camuses on the playing field. Unlike so many French politicians and so-called “philosophers” (as omnipresent on French talk shows as political pundits are on ours) Stora was not interested in instrumentalizing Camus to serve his own polemical ends. Rather — and this comes through more than anything after reading the scenario for the exhibition, which he provided to us — Stora wanted to accompany the visitor on an exploration of Camus that would be anything but anodyne, critical in today’s France, where Camus has often acquired the dusty, neglected state of required high school reading. Incredibly, Stora has succeeded in arranging his biographical and theoretical progression in a way that, by showing Camus’s thought not in permanent definition but in a struggle — a sort of marmite never finished — brings him to life and makes a quest to apprehend him as a living enterprise. This is not to say that Camus’s over-riding ethos lacks definition.

“Albert Camus was, finally,” Stora writes in the conclusion of the proposed scenario for the exhibition, “he who refused the spirit of the system and introduced in the political act the sentiment of humanity. To those who believed that only violence is the grand decider of history, he said that yesterday’s crime can neither authorize nor justify today’s. In his appeal for a civil truce (to the Algerian War), secretly prepared with the Algerian director of the FLN Abane Ramdane, he wrote in January 1956, ‘Whatever the ancient and profound origins of the Algerian tragedy, one fact remains: No cause can justify the death of the innocent.’ He believed that terror against civilians is not an ordinary political weapon, but destroys the real political field. In ‘Les Justes,’ he has one of his characters say: ‘I have accepted killing to overthrow despotism. But behind that which you say, I see the announcement of a despotism which, if it is ever installed, will make of me an assassin when I am trying to be a champion of justice.’

It might be hard to conceive of this today, when philosophers and politicians — particularly in France — are uniformly interested in advancing their own world views, but in his books as in his life, Camus was as likely to be in a quest for understanding as to be interested in imposing his own solution. “As a contra-courant to the hate which flowed during the Algerian War,” Stora writes, “Camus tried to understand why this couple, France and Algeria, apparently welded together, was breaking apart with such a big fracas.” In the flood of wounded spirits and souls, “always taking the side of the trouble-maker, Camus continues to intrigue. Relation to violence, refusal of terrorism, fear of losing those close to him and his land, belief in the necessity of equality and blindness before the nationalism of the Algerians — his oeuvre appears like a palace in the fog. The closer the reader gets, the more complicated the edifice becomes — without at all losing its splendor.”

Indeed, Algeria might be to Camus’s philosophy as the Sun was to Mersault, the hero of his breakthrough novel “The Stranger”; he is too close to it, so it temporarily blinds him, challenging the consistency of his otherwise pure philosophy and unwavering moral compass.

In his classic distillation of Camus’s thought, “Camus” (Fontana Modern Masters, 1970, p. 59), Conor Cruise O’Brien writes: “Eight years after the publication of ‘The Plague,’ the rats came up to die in the cities of Algeria. To apply another of Camus’s metaphors, the Algerian insurrection was ‘the eruption of the boils and pus which had before been working inwardly in the society.’ And this eruption came precisely from the quartier in which the narrator had refused to look: from the houses which Dr. Rieux never visited and from the conditions about which the reporter Rambert never carried out his inquiry. The realization of this adds a new dimension to the sermon. The source of the plague is what we pretend is not there, and the preacher himself is already, without knowing it, infected by the plague.”

This is the beauty of the imperfection of Camus: He may realize he cannot be completely morally consistent on the Algerian question, and yet he forges on. This is the courage of Benjamin Stora’s vision for the story of Camus he sought to tell: there would be no clear moral conclusion for him to present to those who undertook to enter the expedition / exhibition — the curator would even encounter some moral land-mines that might be treacherous for him to traverse because of his own experience with this central theme — and yet he forged on, not to prove a point but to reveal a life.

It’s clear, then — to return to the palace in the fog metaphor — that even if his own personal experience and political sentiments may differ from Camus’s (and I’m not saying they do; I am no expert on Stora and his thinking), Stora does not let this blind him to the grandeur of his subject and it’s that grandeur that comes through in his scenario for this exhibition.

Unfortunately, the France into which Stora dropped this is compositionally the same factional and fractured France in which Camus frequently managed — and isn’t this the true sign of an objective thinker? — to distance, even alienate people on both sides, the Right and the Left — in this specific case, those who wanted to hang on to Algeria and those who championed its Independence. And those so blinded by their own point of view they cannot see the big picture. So it was that the exhibition was torpedoed last Spring, quite possibly because the mayor of Aix-en-Provence (the city’s point person on the Marseille – Provence Cultural Capital of Europe 2013 committee was none other than the mayor’s daughter) apparently decided, with no factual grounds, that Stora’s exhibition would be too pro-FLN (the Algerian independence forces), and that this might offend the many ‘pieds-noir’ among her constituents, ethnic French who fled Algeria when it won its Independence in 1962. (This is just one of the conjectures raised by the French media to explain the exhibition’s annulation. I don’t present it as proven fact.) When Aix tried to resuscitate the exhibition in September — with an exhibition commissar whose more narrow focus on Camus as anarchist and free-thinker has made him the darling of a nascent (if harmless) movement of proto-“anarchists” nostalgic for their forebears of the turn of the (20th) century (“anarchists” are now to France as “hipsters” are to the U.S.) — the French government finally stepped into the fracas, with newly appointed Culture Minister Aurelie Filippetti defending Stora and withdrawing the government’s official imprimatur from the revived exhibition with Stora replaced. The new commissar, Michel Onfray, ultimately withdrew. (I am not delving more deeply into the reasons for the cancellation of Stora’s exhibition because, in fact, the more one delves into it the more it resembles the afore-mentioned castle in the fog — without the splendor — and, more important, where most of the coverage of the exhibition has focused on the controversy surrounding its cancellation, our purpose here is to illuminate the actual exhibition planned by Stora — and advocate for its being revived.)

What’s needed now is for Filippetti to take Camus-like action and provide a State rubric and facility for Stora’s exhibition, ideally the Bibliotheque Nationale, whose location in Paris’s student nucleus of the 13th arrondissement also makes it ideally located to attract the audience for whom this exhibition, which extracts Camus from the treatise and brings him to life again, is most essential. Doing so would conform to one of new French president Francois Hollande’s stated priorities: young people. Says Stora, in the preliminary scenario:

“Our intention in this exposition is not to ‘reconcile’ those who like Camus and those who reject him for all kinds of political, aesthetic, or literary reasons. What we want to say is not, despite its appearance, subjective: Camus was, and remains, a writer for the young. Not because he died at 46. At that age, or even younger, an abundance of writers, musicians, painters, and artists, from Schubert to Van Gogh, have created mature oeuvres. But Camus offers something singular to young people: He starts with acute discoveries, followed by a reaction almost always generous, and we think that generations of high school and college students continue to recognize themselves and to be shaken, awoken, revealed to themselves.”

Several years ago then-French president Nicolas Sarkozy floated the idea of moving Camus’s body from the cemetery of Loumarin in the southern department of Vaucluse to the Pantheon, where reside the ‘glorious ones’ of France. (Actually, the glorious men and Marie Curie.) Filippetti now has an opportunity to champion Camus’s place as perhaps the most glorious exponent of French thought since Descartes, that is to say French thought at its most glorious: As an inquisitive explorer of ideas. Technically, the moral rights (as they’re called in France) to the Camus artifacts which make up much of Stora’s planned exhibition may belong to Catherine Camus, his daughter; but don’t they really belong to all his sons and daughters, and thus does not this patrimoine or heritage ultimately appartient to the State acting on their behalf and in their interests?

.

*”No, the ‘good people’ don’t like it when you don’t follow the same path as them.”

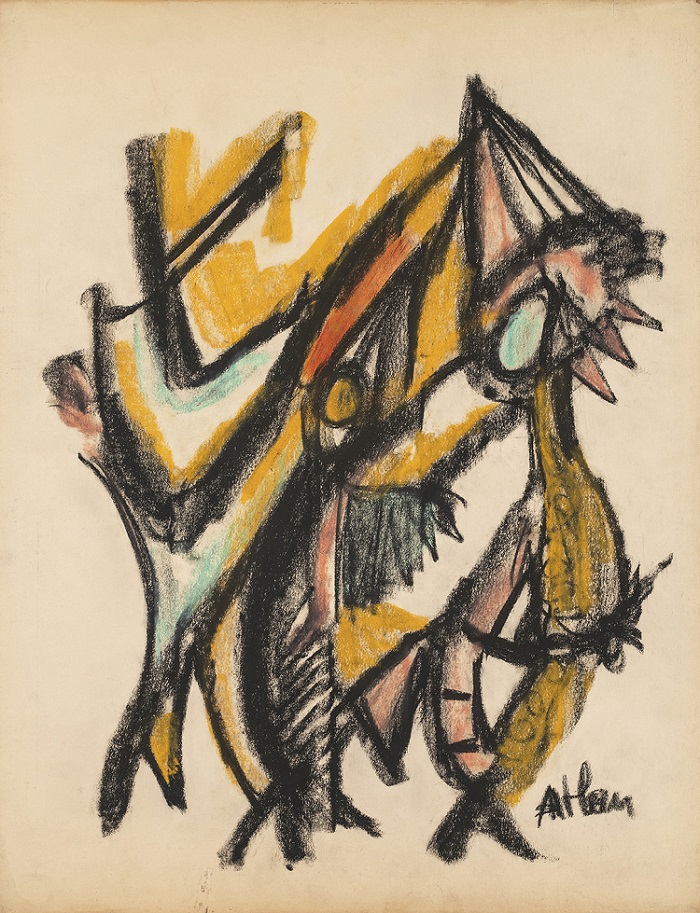

Often lost among the quarrel between the Abstracts and the Figuratives of the 1950s (and the critical partisans of their schools) was the achievement of work which — sometimes depending on the eye of the viewer — traversed both terrains. Thus it is no surprise that for an exhibition which by its name alone, Animal Totem, promises a degree of concreteness, the Galerie

Often lost among the quarrel between the Abstracts and the Figuratives of the 1950s (and the critical partisans of their schools) was the achievement of work which — sometimes depending on the eye of the viewer — traversed both terrains. Thus it is no surprise that for an exhibition which by its name alone, Animal Totem, promises a degree of concreteness, the Galerie