From the Arts Voyager / Paris Tribune archives: From our coverage of the 2018 Museum of Modern Art exhibition Is Fashion Modern?, Display figures with hijab, in East Jerusalem market. Photo by Danny-w. Some rights reserved. Used through Creative Commons. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

From the Arts Voyager / Paris Tribune archives: From our coverage of the 2018 Museum of Modern Art exhibition Is Fashion Modern?, Display figures with hijab, in East Jerusalem market. Photo by Danny-w. Some rights reserved. Used through Creative Commons. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

Fashionistas, 2: Impressionism, Fashion, & Modernity at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Ignore the conceit, go for the paintings

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “The Millinery Shop,” ca. 1882-86. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 43 5/8 in. (100 x 110.7 cm). the Art Institute of Chicago. Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Text copyright 2013, 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

First published on our sister magazine the Arts Voyager on February 12, 2013, today’s re-posting of this story and the above related piece is dedicated to F.I., M.C., and V.S. in sincere appreciation of a stimulating evening et moment de partage and in the spirit of our continuing search for inter-cultural understanding. Like what you’re reading? Please let us know by making a donation today. Just designate your payment through PayPal to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. No amount is too small. To translate this article into French or another language, please use the translation engine button at the right of this page.

If context illuminates in Cezanne and the Past, on view at the Budapest Fine Art Museum through February 17, for Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art February 26 and running through May 26, it threatens to obscure (at least if one is to judge by the press release). Co-curated by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Musée d’Orsay, the exhibition’s thematic presentation seems to super-impose a subject-driven mode of operation which was never the Impressionists’ primary concern. Subject was important only insofar as it provided a prism for light and a means to experiment with other technical elements like volume and color values. If sentiment (Cézanne and Morisot) and social concerns (Pissarro) often also figured into the mix, and if it’s true that some revolutionized the art and bucked public and critical ridicule when they introduced modernity (Manet and Cézanne again), and many more incorporated new sciences like photography (Degas and the Nabis), the Impressionists were not so concerned with following “the latest trends in fashion” (as the Met’s PR puts it). So unlike Cezanne and the Past, where the artist’s career-long revisiting of his predecessors is well-documented, the primary impetus here seems to be marketing. That said, if you can set aside the feeble premise, the exhibition (which promises 80 paintings and supplementary material) is still worth seeing for the way it follows first and second-tier (notably Caillebotte, who was also an influential collector) Impressionist painters and their contemporaries (Fantin-Latour’s portrait of Manet is a revelation; Tissot here rivals Monet in color vibrancy) into corners of 19th-century Parisian life where we don’t usually see them: Degas takes a busman’s holiday from painting nudes to visit a millenary, and from sketching the ‘petites rats’ of the Paris Opera school to capture the august stockbrokers of the Bourse; Caillebotte then follows them to one of their plushy clubs, perhaps on the rue Victoire. In other words, if you can ignore the sexy (if tired) conceptual premise, you still might be seduced.

For additional commentary, please see the captions below.

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection.

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection.

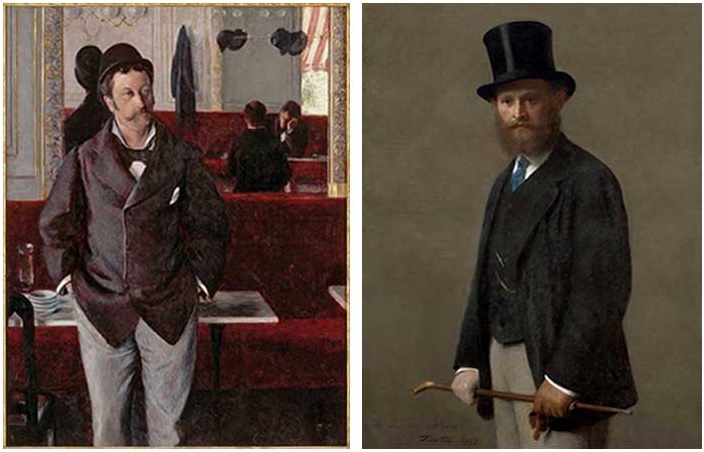

Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.)

Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.)

Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart.

Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart.

Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry.

Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry.

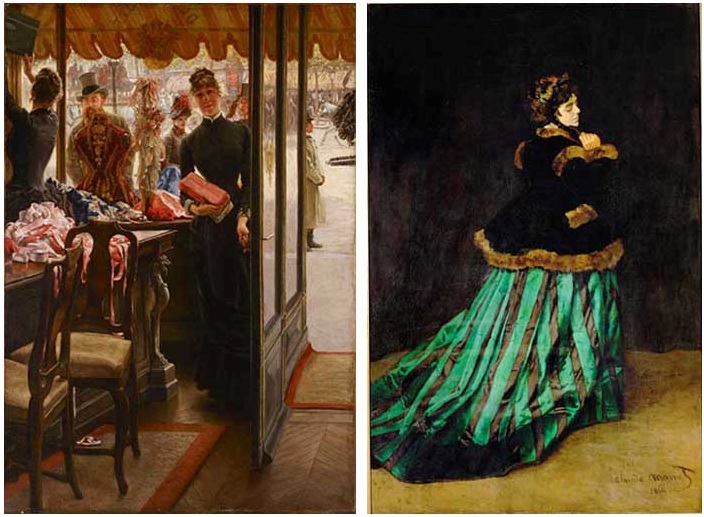

Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen.

Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen.

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color.

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color.

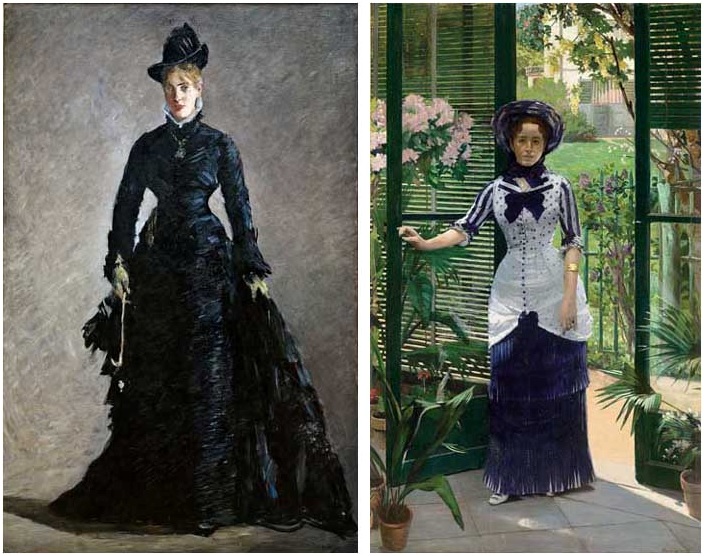

Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

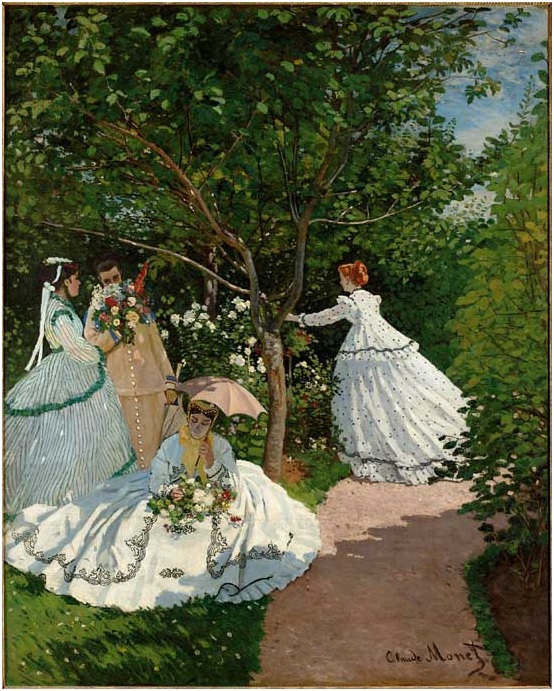

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Women in the Garden,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 100 3/8 x 80 11/16 in. (255 x 205 cm) Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

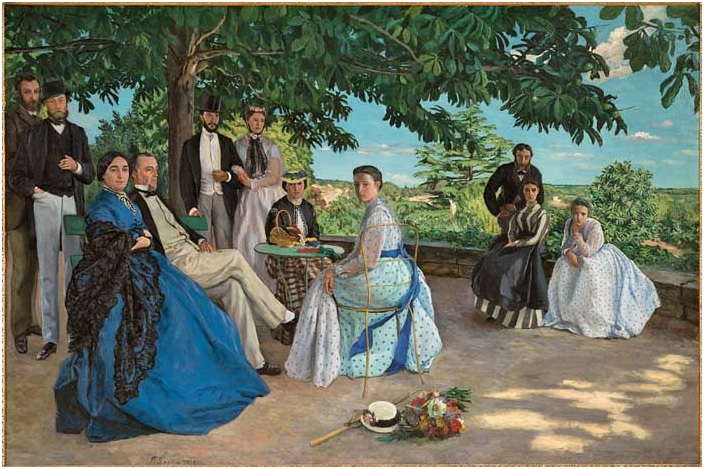

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone.

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.

Paris to Villeneuve-sur-Lot: How the Southwest was won by a gallerist in Saint-Germain des Pres

Jean Dubuffet, “Site domestique (au fusil espadon) avec tete d’Inca et petit fauteuil a droite,” 1966. Vinyl on canvas, 125 x 200 cm. Fascicule XXI des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, ill. 217. Copyright Dubuffet and courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

Jean Dubuffet, “Site domestique (au fusil espadon) avec tete d’Inca et petit fauteuil a droite,” 1966. Vinyl on canvas, 125 x 200 cm. Fascicule XXI des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, ill. 217. Copyright Dubuffet and courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Text copyright 2014, 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

First published on the Paris Tribune’s sister magazine Art Investment News on September 14, 2014. (Like what you’re reading? Please let us know by making a donation today. Just designate your payment through PayPal to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. No amount is too small. To translate this article into French or another language, please use the translation engine button at the right of this page.)

PARIS — Accessibility has become a dirty word, with its implication that to reach the masses, art must be dumbed down. But truncate the word to “access,” and you understand the collaboration that the municipality of Villeneuve-sur-Lot in Southwestern France — a region better known for the fertility of its grapevines than the fecundity of its modern art scene — and the legendary Saint-Germain des Pres gallerist Jean-Francois Jaeger of the Gallery Jeanne Bucher Jaeger have forged over the past 45 years, under which the anything but hic residents of this ‘provincial’ town have been able to experience the contemporary art revolution(s) of the ’50s, ’60s, and beyond contemporaneously with the putatively hip Parisian public. This complicity is being celebrated, through October 26, at the Musee de Gajac, a converted Villeneuve flour mill, in “A Passion for Art: Jean-Francois Jaeger and the Gallery Jeanne-Bucher Jaeger,” with work selected by the 90-year-old honoree which, true to form, prizes mystery over mediocrity and discovery over dilettantism.

If the Gallery Jeanne-Bucher has fulfilled the central mission of a contemporary art gallery for nearly 90 years, as an avatar (or avant-garde for the avant-garde) for Cubism (exhibiting Braque, Picasso, Gris…), Abstraction (Kandinsky, Mondrian, Klee, Arp…), and Surrealism (De Chirico, Ernst, Giacometti, Masson, Miro, Tanguy, Picabia…), Jeanne Bucher was not looking to attract solely the Parisian and international cognizanti to her gallery on the rue de Cherche-Midi (later on the boulevard Montparnasse and eventually the rue de Seine) when she founded it in 1925, but to “diffuse the taste for art amongst all classes.” Jaeger, who took over direction of the gallery in 1947 (officially succeeded in 2003 by his daughter Veronique), has implemented that mission with aplomb by loaning or arranging the loans or gifts of contemporary art to the Gajac Museum and its predecessor institutions in Villeneuve and its environs, notably for two biennales and four major exhibitions since 1969, dedicated variously to Roger Bissiere and Friends (the friends including Andre Lhote and Georges Braque); Hans Reichel; artists of Algeria and the South; and Spanish artists persecuted by Franco, many of whom found refuge in Southwestern France. Bissiere, a native of the region, is accorded a central place in the oeuvres selected by Jaeger (given carte blanche by the museum, an indication of the trust he’s earned with the community) for this latest exhibition, accompanied by major examples from Jean Dubuffet, Vieira da Silva, Louise Nevelson, Fabienne Verdier, Hans Reichel, Mark Tobey, Nicholas de Stael, Fermin Aguayo, Yang Jiechang, Jean Amado, and Susumu Shingu, the ensemble promising “que d’aventuresoffered to our curiosity, to our search for a real initiation,” as Jaeger puts it. He goes on to praise the Gajac museum as “one of our best provincial museums.” When most Parisians use the term ‘provincial,’ they mean it as an insult, but Jaeger is speaking strictly geographically; there’s nothing provincial about the Gajac programming, which seems more interested in “initiating” its public in major 20th- and 21st-century artistic currents than providing fleeting encounters with random works or catering to existing tastes with sure box-office hits. By comparison, it’s the major exhibitions in Paris and New York this summer that have seemed provincial, with the Petite Palais re-visiting (encore?!) “Paris 1900,” the Pompidou the relationship between Breton and Picabia, the Orsay Van Gogh (albeit as analyzed by Artaud), and New York’s Museum of Modern Art the Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec.

Nicolas de Staël, “Jour de Fete,” 1949. Oil on canvas, 100 x 73 cm. No. 176 of Catalogue Raisonne. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

What unites most of the work on display in Villeneuve-sur-Lot is not just that it favors the abstract over the figurative, but that this is abstract art whose complexity invites the viewer to engage. This kind of engagement doesn’t happen overnight. Like the dark malbec-based Cahors wine in the county of the Lot which neighbors Villeneuve-sur-Lot, it’s the fruit of years of cultivation. And indeed, it was more than 50 years ago that the artistic brain trust of Villeneuve-sur-Lot started planting the seeds of artistic appreciation in its community. (The other factor that unites most of the artists in this exhibition, is that — with the exceptions of Dubuffet and de Stael, who can be seen as the elders of the epoch — most are part of a generation of artists who flowered from the late ’40s to late ’60s, a lost generation in the institutional memories of most big-city museums.)

In 1963, as Jacques Balmont, a printer by trade, recounts to Emmanuel Jaeger in the presse dossier for the exhibition, Balmont got together with Rene Verdier, local salon organizer Maurice Fabre, municipal art school founder and painter Pierre Raffi, and bookseller Robert Bonhomme to organize an annual exhibition open to both professionals and amateurs. After successive shows on provincial painters in 1964 and ’65, this informal committee increased the ante in 1966 with an exhibition devoted to the fauve (and Bordelaise) artist Albert Marquet — signaling that they understood something even schooled curators seem to forget, that a museum has a responsibility to rescue significant artists from the ‘oublie.’ (When I meet otherwise cultured young and not-so-young people — even artists — who don’t know who Suzanne Valadon, Berthe Morisot, Marie Laurencin, and Leonor Fini are, I assign their ignorance to the irresponsibility of the museum directors and curators whose sexism has excluded these major artists.) This interest by the local artistic brain trust in highlighting the ‘second tiere’ (not to be confused with ‘also ran’) of major mid-20th century movements continued in 1967 with a biennale featuring 48 works by another Bordeaux-born artist, Andre Lhote, culled principally from Lhote’s widow. But they didn’t stop there; the biennale also included work by Clave, Pignon, Chastel, Louttre-B and 150 provincial painters.

Roger Bissiere, “Vert et Ochre,” 1954. Oil on jute canvas, mounted on contreplaque. Courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

For the next biennale in 1969, it was time for Balmont and associates to finally combine their fidelity to local talent with their curiosity about under-represented international-caliber artists, and for this one figure presented himself: the recently deceased Roger Bissiere, a master of post-War abstraction born in nearby Villereal. Enter Jean-Francois Jaeger.

When the Villeneauve team sought out Bissiere’s son, he told them that they absolutely needed to enroll Saint-Germain des Pres gallerist Jaeger and the Jeanne-Bucher Gallery, which had represented Bissiere since 1951. They would have been happy with enough tableaux for an exhibition focused solely on Bissiere, but Jaeger — in a pattern that would repeat itself over the next 45 years — was thinking bigger. He proposed instead to expand the event under the rubrique “Bissiere and Friends.” “And what friends!” recalls Balmont. In addition to 67 paintings, three tapestries, and 10 lithographs by Bissiere, the exhibition at the Theatre Georges-Leygues included work by Braque, Lhote, Vieira da Silva, and Hans Reichel. This in turn ‘enchaine’ed into a fourth biennale in 1971 consecrated principally to Reichel, a disciple of Bauhaus and compagnon de route of Paul Klee, Lawrence Durrell, Henry Miller, and Anais Nin. The nexus was once again Jaeger who, from the collection of the Jeanne-Bucher Gallery, Reichel’s companion, and private holdings secured 75 watercolors and paintings dating from 1921 to 1958. This grandeur of vision — augmented by a complementary exhibition of other artists — contrasted comically with the seat of the pants logistics, which saw Balmont and his colleagues transporting large-scale works by Hans Hartung, Serge Poliakoff, and others from Paris to the south with municipal trucks typically reserved for filling pot-holes.

The heart of any museum is its permanent collections, which serve both as a pedagogic reference and a potential treasure chest for future acquisitions. Perhaps impressed by the community’s seriousness in establishing an acquisition fund in 1976, Jaeger next convinced Louttre-B, Bissiere’s son, to make the Musee Rapin, Gajac’s predecessor museum, the depository for his 220 existing engravings and any to come.

Unfortunately, the downside of government investment in the arts is that it leaves the arts vulnerable to changes of personnel and policy (curators propose, politicians dispose….). (That the legendary French singer-songwriter Charles Trenet is its most famous export didn’t stop the new mayor of the Languedoc town of Narbonne from de-funding and effectively canceling this year’s edition of the prestigious Trenet festival. And while Villeneuve’s current mayor proudly proclaims the town’s policy of making culture “accessible to all,” Alain Juppe, mayor of the regional capital of Bordeaux, former prime minister, foreign minister, and presidential candidate, recently revealed himself as a small thinker when it comes to the arts by eliminating free access to the permanent collections of the municipal museums.) Thus it was that Jaeger’s subsequent enlistment of Francis Mathey, who as chief conservateur of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris had introduced Dubuffet, Balthus, Yves Klein, Pierre Soulages and a generation of young artists in France (“One of my mentors,” Jaeger says, “the first to open his museum to living artists never before exhibited in France”) in Villeneuve’s artistic future went for naught after a new government elected in 1977 lost interest in the project. It took 25 years and another change at city hall for a planned museum of art and history of the Valley of the Lot in a renovated ancient mill to be re-oriented into a museum of beaux-arts. Once again, indigenous resources and the global view of Jaeger combined in 2003 for the (re) inaugural exhibition, “Mere Algere, couleurs de Sud,” whose fount was several works donated by Maria Manton, part of the brain trust of previous exhibitions and a major Algerian-born artist. Next came “L’action pensive” in 2007, built around post-war giants of Abstraction like Nicholas de Stael, Poliakoff, Bissiere, Vieira da Silva, and Louis Nollard, followed in 2008 by “La representation pensive,” dedicated to figurative artists of the same epoch, with oeuvres lent by the Centre Georges Pompidou, the Museum of Modern Art of the city of Paris, and the Fondation Dubuffet. The ante was upped even further in 2010. Inspired by commemorations of the 80th anniversary of the Spanish Civil War, and cognizant of the region’s role in welcoming exiles of the Franco regime, Jaeger and crew programmed “Spain, the dark years,” convincing leading French and Spanish museums to loan work by Miro, Julio Gonzalez, Fermin Aguayo, and even Picasso’s tapisserie for “Guernica.”

In the press dossier for “A Passion for Art: Jean-Francois Jaeger and the Jeanne-Bucher Gallery,” Emmanuel Jaeger, noting the evident complicity between Balmont and Jaeger, asks the former whether there’s any single element linking Villeneuve and the gallery.

“It was after ‘Bissiere and his Friends’ and ‘Hans Reichel’ that a friendship was really born between us,” Balmont recounts. “Every time I go to Paris, my route takes me immediately to the rue de Seine, to see Jean-Francois. Our conversations have enriched me as privileged moments of discovery and knowledge…. Besides the links of friendship, of a cultural connivance, I think that Jean-Francois was drawn to our little provincial town which made the choice early on to expose its citizens to the art of its time. The will of the Gajac Museum to initiate, to democratize modern and contemporary art corroborate perfectly the fabulous trajectory of Jean-Francois and the Gallery Jaeger-Bucher/Jeanne-Bucher.” And for Jaeger, “Every return to the country of Bissiere procures for me an intense emotion and vivid sentiment of recognition for he who taught me everything when I was just beginning.” Not that the education ever stopped. “It’s in the contact with artists, and the example of their own permanent curiosity, that we have been able to refine our knowledge, not in the history of art but in its practice, in the service of those on whom destiny had conferred special gifts,” says Jaeger. “Those who make history do not constantly refer to the past, but listen to what a creator’s temperament can bring them to discover in themselves.”

Trolling the galleries around Saint-Germain des Pres on a late July afternoon, starting out on the rue de Seine, I wandered into a deserted courtyard at the base of which was an unobtrusive gallery. With no glitz and nary a mis-en-scene, the four walls sported treasures by Bissiere and Vieira da Silva, among others, which expressed not only their authors’ visions but the zeitgeist of a whole artistic era. A young woman dressed in black was occupied scribbling notes behind her desk. From a desk near hers, a dapper man dressed in a drab brown suit, tan slacks, and dark loafers murmured something before slowly rising to take the air outside the gallery. No glamour. No glad-handling. (And no other visitors in the gallery besides me.) And yet this was the man who, with no fanfare, has for nearly 70 years quietly created a home for contemporary artists typically ignored (until they’re dead anyway) by the major museums (Dubuffet was for years excluded by the Pompidou) not only in the heart of artistic Paris but, in a France perpetually obsessed with ‘decentralization’ (it even has its own ministry) in France profund. In a milieu more and more dominated by art dealers, Jean-Francois Jaeger is an art promulgator, ensuring that art doesn’t remain the province of the privileged but privileges the provinces.

Back to Africa: Cubism at Beaubourg

Among the more than 300 works on view through February 25 at the Centre Pompidou for its exhibition Cubism is, above, “Masque krou,” Côte d’Ivoire, undated and uncredited. (The museum actually credits the work to “anonymous,” but of course the artist had a name.) Painted wood, metal, and cork. 25.5 x 16.5 x 18.3 cm. Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon, Lyon. © Lyon MBA – Photo Alain Basset.

Among the more than 300 works on view through February 25 at the Centre Pompidou for its exhibition Cubism is, above, “Masque krou,” Côte d’Ivoire, undated and uncredited. (The museum actually credits the work to “anonymous,” but of course the artist had a name.) Painted wood, metal, and cork. 25.5 x 16.5 x 18.3 cm. Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon, Lyon. © Lyon MBA – Photo Alain Basset.

Yes, Hergé’s drawings in “Tintin au Congo” are colonialist, racist trash (revised with expanded text 16h00)

“I made ‘Tintin au Congo’ without a lot of enthusiasm…. Practically everyone was Colonialist (at the time)…. ‘The white’s role was to bring civlization to the blacks.’ Tintin wasn’t racist, he was Colonialist like everyone was in the epoch.”

— Hergé

Bravo for Casterman’s decision not to re-publish Hergé’s “Tintin au Congo” — as part of a general re-edition of the graphic novels to mark the 90th anniversary of the character — whose drawings, like his depictions of Indians in “Tintin in America,” are racist, colonialist garbage.

Hergé’s disengenous argument — let’s call it lache — that he was just reflecting his epoch doesn’t hold water for anyone who’s red Eugene Sue’s 1842-43 “Les Mysteres de Paris.” Eight-six years before Hergé sorted his bug-eyed, pink-lipped Africans, Sue’s most noble character — perhaps the only personage in the 1,000-page serialized saga beyond reproach — was the African-American Dr. Paul. And when I visited Antwerp in 2003, the same bug-eyed, fat Black people could still be seen peering from post-cards geared to tourists. Belgium has a long Colonial history of racism which was still showing its vestiges in this millenium, and it’s this tradition that begat the father of Tintin.

— Paul Ben-Itzak

How a scholar and a museum tried to take away the mystery from the Creation of the World

From the exhibition Sigmund Freud, From Seeing to Listening, on view at the Museum of the History and Art of Judaism through February 10: Gustave Courbet, “L’Origine du monde” (The Creation of the World), 1866. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. © Paris, musée d’Orsay.

From the exhibition Sigmund Freud, From Seeing to Listening, on view at the Museum of the History and Art of Judaism through February 10: Gustave Courbet, “L’Origine du monde” (The Creation of the World), 1866. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. © Paris, musée d’Orsay.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

(Like what you’re reading? Please let us know by making a donation today. Just designate your payment through PayPal to paulbenitzak@gmail.com, or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. No amount is too small. To translate this article into French or another language, please use the translation engine button at the right of this page.)

PARIS — A sort of anthropological elaboration on his discovery that the model for Gustave Courbet’s alternately maligned and celebrated 1866 painting “L’origine du monde” (most recently in the news when the luddites at Facebook tried to ban it; okay to use us to recruit terrorists, but art is too dangerous) was the Paris Opera Ballet dancer Constance Quéniaux — the author uses her trajectory as a window into the world of the late 19th-century Parisiennne courtesan — Claude Schopp’s “L’origine du monde: Vie du modèle,” published by Phébus, should be required reading in schools of journalism, for both its positive demonstration that investigative journalism relies as much on scrupulous research as vigorous legwork and its negative example of how to pad out (or as the French say, embroider) a story. Given that Schopp has singularly taken the mystery out of a major work of art that managed to retain it for 150 years, the achievement is dubious.

It’s easy to forget, in this era of “gotchya” journalism, the example set for my generation of Woodstein wannabes by the Washington Post reporters who brought a president down. They did this not by digging in the White House trash-cans but because a cops reporter named Bob Woodward had his ears perked and was smart enough to recognize the national implications of a local hotel break-in when it came up on the municipal court docket.

Claude Schopp’s solving of a mystery which has intrigued art aficionados since the work Anglophones know as “The Creation of the World” was created in 1866 came in an even more staid setting, the musty research rooms of the French National Library on the Seine. And it came because Schopp is what the late Joseph H. Mazo, one of my mentors, used to call (as in I’m looking for) “an anal copy editor.”

The leading living expert on Alexander Dumas Jr., Schopp was preparing a book on the correspondence of the latter with George Sand, the good woman behind at least four great men of 19th-century European arts and letters (Chopin, Dumas senior and junior, and Flaubert). He’d already revealed, in “Alexander Dumas, Jr. — the anti-Oedipus” (Phébus 2017) how the son had rescued a batch of love letters between the woman he referred to as “Mom” and Chopin (while chasing after his own elusive mistress in an obscure Slavic border town), subsequently burned by Sand. That book also proved that Schopp does not have his head buried in the past; the revelation of a screed Dumas Junior had written supporting a law (still on the books at least as recently as 1872) which gave a man the right to kill his unfaithful spouse helps explain what some see as the retrograde status of women in contemporary France; they’ve had a long way to come, Baby. (Junior, who as the author of “Camille” might have been expected to have more sympathy for women, terminated his piece with “Kill her!”)

So it’s no surprise that this reactionary, no friend of the Paris Commune (organized by Parisians who refused Versailles’s surrender to the Prussians), would pen a report for the Rouen News on June 6, 1871 lambasting its most prominent artistic avatar: Gustave Courbet, who had famously brought down the Vendome column (as being a symbol of Versailles) and was subsequently ruined when he was forced to pay for its restoration.

“What kind of fabulous copulation of a slug and a peacock,” Dumas asked, “what procreative antitheses, what sebaceous oozing could have possibly generated, for instance, this thing known as Gustave Courbet? Under what blister, with the help of what compost, as the result of what mixture of wine, beer, and corrosive mucus and flatulent edema could this pilose, loud gourd, this aesthetic stomach, this incarnation of the imbecile and impotent Me have sprouted?”

Mlle Constance Quéniaux par Disdéri, BnF, département des Estampes et de la Photographie.

It was while examining the transcription of Dumas Junior’s response to the letter “Mom” must have subsequently written him defending Courbet (as Dumas’s letter suggests; the Sand letter to which he’s presumably responding is lost) that Claude “Eagle-Eye” Schopp stumbled on the identify of the model for “L’origine du Monde”:

“There’s no excuse for Courbet — this is why I piled it on,” Dumas explains to Sand. “When one has his talent which, without being exceptional, is remarkable and interesting, one doesn’t have the right to be so proud, so insolent, and so cowardly — not to mention that one simply does not paint with such a delicate and sonorous paintbrush the *interview* (emphasis added) of Mademoiselle Quéniaux of the Paris Opera Ballet, for the Turk who dwelled there from time to time, above all in such an in-your-face, natural manner, not to mention painting two women passing as men,” the latter a reference to the painter’s “Sleep,” in which two luxuriant odalisques cuddle in a nap. “All this is ignoble…. Compared to this I’ll forgive him for toppling the Vendome column and suppressing God, who must be laughing like a little fool.”

Struck by not just the senselessness but the epoch and language incongruity of the English word “interview” in a letter from 1871, Schopp asked to examine the original manuscript in the Library’s collection, and discovered that the handwritten word was clearly not ‘interview’ but *intérieure* — the word is underlined, and easily legible even in the reduced reproduction in the book, including that accent over the first e.

For a rigorous scholar like Schopp, though, this wasn’t good enough, so he then set about looking for connections between the four principals — Courbet, Quéniaux, Dumas Junior, and the evident Turk in question, the Ottoman ambassador and playboy Khalil Bey, who had been the dancer’s lover. Thus it was that he uncovered that the painting had been a vanity commission for the painter from “the Turk” — paint my mistress — and who subsequently kept it hidden behind a curtain in his salon, with only the select privileged with an occasional viewing. (Schopp also found accounts from some of these contemporary witnesses.) The Dumas-Bey and Dumas-Quéniaux connections — which would explain how the writer had access to this intimate knowledge — are more sketchy; Dumas’s lover was Quéniaux’s best friend, and the writer and the ambassador had at different points both bought at auction Delacroix’s 1839 painting, “La Tasse dans la maison des fous,” which inspired Baudelaire to write (and which I know because the poem illustrates the painting’s or a drawing of its appearance in a 1905 auction catalogue in my own possession):

Le poète au cachot, débraillé, maladif,

Roulant un manuscrit sous son pied convulsif,

Measure d’un regard que la terreur enflamme

L’escalier de vertige où s’abîme son âme.

(The poet in solitary confinement, slovenly, darkly pensive

Rolling a manuscript under his foot so convulsive

Realizing with a regard that the terror like fire to coal

is consuming the vertiginous stairwell roughing up his soul.)

(Click here to read more of the poem, in French and in English translation.)

So far so good but still not enough to justify a whole book, so Schopp pads it out with a portrait of the world of the demoiselles that is not particularly original for anyone who’s read Balzac or Zola, except in a conclusion where he adduces Quéniaux as the proof that not all courtisans ended up like Zola’s Nana or Dumas Junior’s Camille, dying young and consumptive after destroying or being deserted by everyone around them. And everything: Schopp goes into much — too much — detail listing all the beautiful things with which the retired dancer went on to surround herself in homes in Normandy and on the rue Royale, not far from the Church de la Madeline. His detailing of her good works — in charity — is more justified, until you get to the part where he supposes, without any evidence, where all this money came from, namely from being a prostitute, or mistress if you prefer. And it doesn’t stop there; he goes so far as to make the generalizing statement that the line between dancer and hooker — or mistress — was fine at the time, the slippery slope of retirement leading from one to the other. I guess Claude Schopp never heard of Marie Taglioni, the Paris Opera Ballet dancer and school founder who was the first to dance on point artistically, and who was still giving classes to English girls when she died.

The other padding is more onerous, consisting of quoting two pages-worth’s (on multiple occasions) of passages from contemporary gossip pages on theater parties or benefits just because Quéniaux makes an appearance, or recurring sequences on an old fogey of an operetta writer whose (platonic) harem included her and, worse, naming every single witness, including their profession and address, who signed every single birth or death certificate of even the most peripheral figures to the tale. It’s as if the very talent which lead Schopp to the discovery — scholarly meticulousness — took over the project, with the means getting confused for the end.

But there’s a larger problem here, and it’s the same one I have with the original painting’s current exhibition at the Museum of Jewish History and Art in the Marais in the (re)context(ualizing) of an exhibition on Sigmund Freud.

The great thing about art is its mystery, the room it leaves for the viewer to collaborate in constructing its meaning. That viewer might be a fancy-schmancy critic like me, or it might be the cowgirl I once overheard telling her cowboy and his friend, on coming upon a Charles Russell painting of two young Indians accompanied by an older women in the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, “Reminds me of our first date; mom insisted on chaperoning us.” In creating the painting whose English title is “Creation of the World,” Courbet offered his viewers the greatest source of mystery in the world, open to multiple interpretations, from the most basic (or base) to the most wondrous. (If he’d wanted it to be a portrait, he wouldn’t have cut her head off.) He invited them to participate in creating his grand oeuvre’s meaning. Schopp has now killed those infinite possibilities by revealing, “It was Constance Quéniaux.” (As the Jewish Museum has done by latching the painting onto Freud, as if his interpretation of the world and juicing up of male complexes around the vagina hasn’t already screwed us up enough.) I’m also reminded of what Andre Malraux said about Degas’s nudes (in the series of lectures that became “The Psychology of Art”), that the subject is not the model but color.

In other words: It’s about the art, stupid. Or to paraphrase Gertrude Stein: A work of art is a work of art is a work of art.

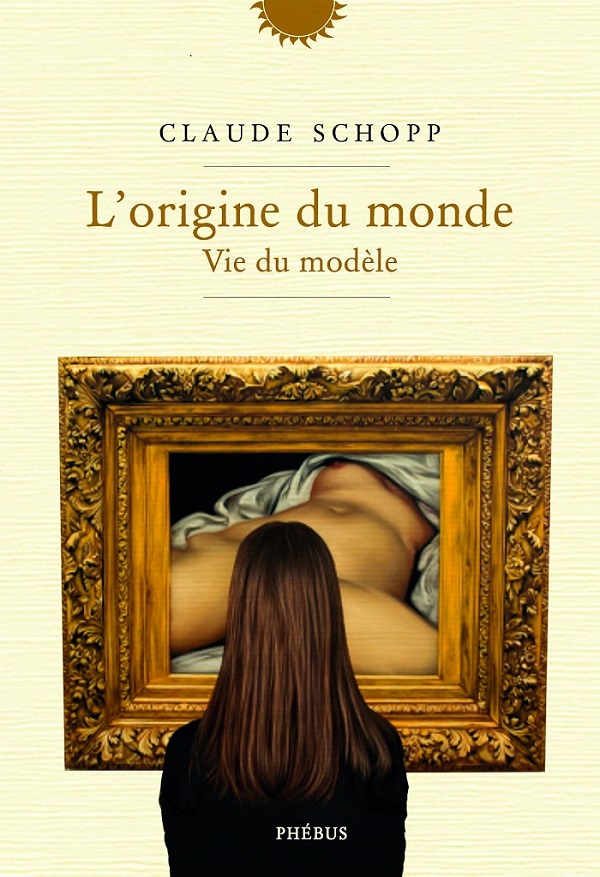

Cover jacket for Claude Schopp’s “L’origine du monde, vie du modèle.”

In the case of Schopp and his publisher, It’s almost as if they just had to take away the mystery and vulgarize it, in both senses of that term. (In French, ‘vulgarize’ means ‘popularize.’) As if it’s not bad enough that a publisher with such an impressively esoteric list (except for the Dumases, I haven’t heard of any of its authors) and a scholar whose previous work, the Dumas Junior biography, operated on a much higher level, plunging into the artistic processes and relationship of father and son, could sink no low, they’ve compounded the vulgarity by the book’s cover. (See illustration.) When I first visited Paris in 2000, I loved how, unlike the cultural fathers and mothers of New York, the French had no compunction about revealing naked bodies in art, in sculpture gardens, and in performance. (No ‘Family Unfriendly’ warnings here.) So why, instead of sticking to that high standard in their cover illustration, have these representatives of French intellectuals sunk to the low level of Facebook, which has infamously banned Courbet’s oeuvre?

The Vanishing French Bench / La disparition du banc française (revised 18h00 Paris time)

The Vanishing French Bench: If photography is a “Class War Weapon” — as the title of the exhibition of work by Andre Kertesz, Dora Maar, Willy Ronis and others running at the Centre Pompidou in Paris through February 4 indicates — then “Bench, Nice,” the above 1936 photo by Pierre Jamet should be plastered all over Paris and its bordering suburbs. In the past 10 years, perhaps as a measure to discourage the homeless from sleeping on them — why solve a problem when you can just make it disappear? — benches throughout Parisian area parks, streets, and Metro stations have been limned to one-person concrete chaises, (in the Metro) lines of pods interrupted by metal posts, or simply disappeared. Observing the traffic from a picturesque bridge over the Ourcq Basin this morning in the frontier suburb of Pantin, I found zero benches as far as my eyes could see on the right side, just a few on the left, and the runners outnumbered the sitters by 100 to zero. It’s a far cry from 2001, when the men sipping their first cafés (or petite blanc, white wine) of the day in the bars lining the rue Rouchechouart would regard me like a bizarre visitor from the future as I wheezed and panted up to Montmartre. Silver gelatin proof, purchased in 2011 with the support of Yves Rocher. Former collection Christian Bouqueret. Press Service, Centre Pompidou, Paris. © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GP. © Pierre Jamet. — Paul Ben-Itzak

The Vanishing French Bench: If photography is a “Class War Weapon” — as the title of the exhibition of work by Andre Kertesz, Dora Maar, Willy Ronis and others running at the Centre Pompidou in Paris through February 4 indicates — then “Bench, Nice,” the above 1936 photo by Pierre Jamet should be plastered all over Paris and its bordering suburbs. In the past 10 years, perhaps as a measure to discourage the homeless from sleeping on them — why solve a problem when you can just make it disappear? — benches throughout Parisian area parks, streets, and Metro stations have been limned to one-person concrete chaises, (in the Metro) lines of pods interrupted by metal posts, or simply disappeared. Observing the traffic from a picturesque bridge over the Ourcq Basin this morning in the frontier suburb of Pantin, I found zero benches as far as my eyes could see on the right side, just a few on the left, and the runners outnumbered the sitters by 100 to zero. It’s a far cry from 2001, when the men sipping their first cafés (or petite blanc, white wine) of the day in the bars lining the rue Rouchechouart would regard me like a bizarre visitor from the future as I wheezed and panted up to Montmartre. Silver gelatin proof, purchased in 2011 with the support of Yves Rocher. Former collection Christian Bouqueret. Press Service, Centre Pompidou, Paris. © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GP. © Pierre Jamet. — Paul Ben-Itzak