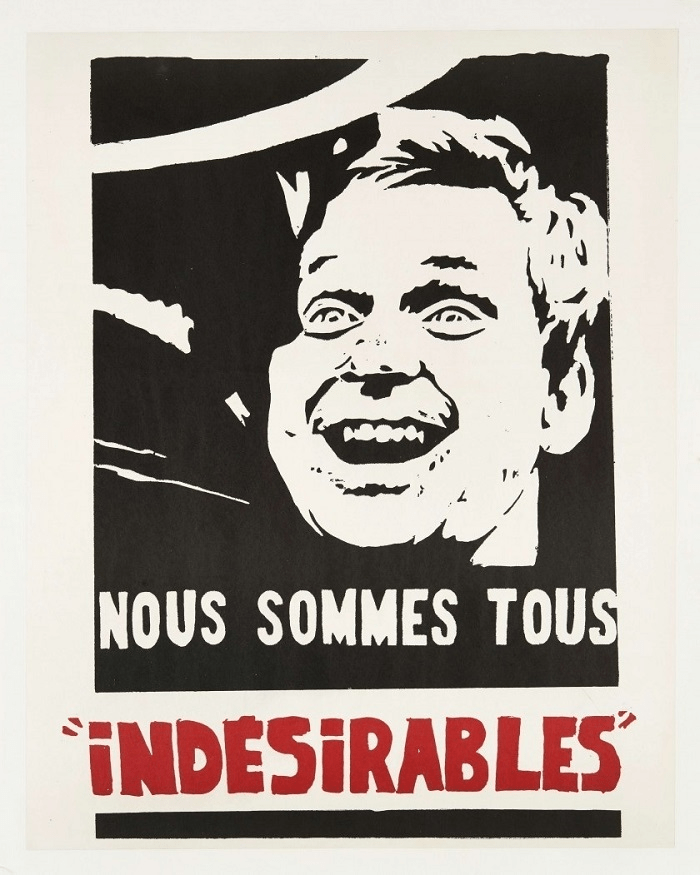

A poster from the May 1968 student and worker protests in Paris which takes as model student leader Daniel Cohn-Bendit, expelled from France as an ‘undesirable’ and later elected to the European parliament as a leader of the Green movement.

by Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2021 Paul Ben-Itzak

First published on the Dance Insider & Arts Voyager on January 20, 2012 and newly edited for today’s publication.

After 15 years of following and reviewing the offerings of New York’s 40+ year-old Anthology Film Archives, easily the best and bravest cinematheque in the United States and one of the top in the world, I think I’m finally beginning to understand what Anthology artistic director Jonas Mekas (a determinedly idiosyncratic independent avant-garde filmmaker in his own right, and founding piston of the SoHo scene of the 1960s) and his colleagues are up to, or rather, how they’ve chosen to manifest it. Historically partial to fiction and less engaged by documentaries, at first I wasn’t particularly keen on the preponderance of the latter at Anthology. But after watching Chris Marker’s “Le fond de l’air est rouge” (cryptically translated as “Grin Without a Cat,” an allusion to Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat) and Sergei Loznitsa’s “Revue” and “Blockade,” all screening in “The Compilation Film” series beginning today at Anthology, I understand that what Mekas and crew are primarily interested in is film that knows it’s film and that fully exploits the medium — and even expands it. Or to paraphrase Jean-Luc Godard’s imperative: One shouldn’t come away from a film feeling like the director simply set his camera before a stage, but that he used it like writer uses a pen.

Witness Marker’s film. Issued in 1978 and ‘re-actualized’ in 1993, “Le fond de l’air est rouge” (more literally translated as “The base of the air is red”) takes as its direct subject various liberation struggles and anti-War crusades of the ’60s and ’70s, many with post-World War II roots. And Marker’s conclusion might seem discouraging, even potentially paralyzing, particularly in the dawn of a new movement essentially founded on the same claim, a more just distribution of wealth: By Marker’s account, all these movements, or if you prefer, The Movement, eventually failed, often because of the faulty execution of the theology which was its fount, Communism. Che Guevara, we’re told in the film, seems to have finally understood that the real enemy was power, whether it called itself Capitalism or Socialism. The Soviet suppression of the Prague Spring of 1968 seems to have woken up Cuban leader Fidel Castro to the fact that Communism was not a de facto guarantor of Democracy, and could sometimes even menace it, as we see during poignant footage in which Castro wrestles in real time — while delivering a speech denouncing the Soviet Union’s sending tanks into Czechoslovakia — with the realization that he must condemn the Soviet invasion, even as he acknowledges that such criticism will play into the hands of “Imperialist” countries.

Perhaps most incredible, in the light of 2011, is a French Communist leader who finally allows, speaking in 1970, that the French Communist Party might just have to collaborate with other parties on the Left to defeat the bourgeoisie. The Communists barely broke 1 percent in the 2007 French presidential election, and in 2012’s they’re not even fielding their own candidate, preferring to back an ex-Socialist Party member. One person who seems to get it right in the film not too long after the events is Larry Bensky, the Pacifica Radio paragon and former Paris editor of the Paris Review, whose powers of analysis often have less lag time than most historians. Interviewed sometime in the 1970s, resplendent in John Lennon circa Abby Road long hair and beard, Bensky says that even though it may seem like there is less activism in the 1970s, today’s activists have already learned a lesson their ’60s predecessors didn’t, the necessity of working together with other groups. (Or what’s known today in 2021– and mocked in neo-Liberal French circles — as “intersectionality.” Une fois de plus, Larry, you nailed it avant l’heure) Even observing the weight Marker gives to French union leaders, both in direct interviews and in footage from demonstrations, is a jarring contrast with the present reality, when few private sector workers belong to unions and many union leaders seem more interested in securing their terrain than effectively advancing a worker-friendly agenda.

Add to the chronology of events covered by Marker the killing of Che, Watergate, the assassination of Chilean president Salvador Allende, and — if I understand his thesis correctly — the lack of any real legacy from France’s May 1968 student movement (although it is moving to see a young Daniel Cohn-Bendit, a.k.a. “Danny the Red,” hold forth in 1968 from the perspective of 2012, when he’s still an influential counter-balance to Capitalism-centric Euro-globalization, as co-president of the Green group in the EU Parliament), and Marker’s evident conclusion that it all whithered away with the disintegration of Communism, and the film might seem depressing… on the editorial level anyway.

Why, then, does “Le fond de l’air est rouge” leave one feeling optimistic?

What’s inspiring about this film — and makes it fit into the Anthology Film Archives mission, as I understand that mission — is how gorgeous, original, and genre-expanding it is as a film. (Marker was, after all, the director of the haunting futuristic photo-film “La jetée.”) To be honest, I was not up for yet another golden-aura’d ’60s re-cap. I even felt that having lived the era as a child growing up in San Francisco, I didn’t particularly need a refresher course and Marker wouldn’t teach me anything new. But with techniques including variously tinted sepia tones — brown, orange, red — as well as his skittish minimalist electronic score, the interweaving of end of WWII footage, film of demonstrations all over the world, direct interviews, speeches of the epoch seen on a television in a darkened room, and even a slow-motion scene from a Chinese propaganda ballet with a woman in red slowly pirouetting and being turned and lifted by a man, Marker has created a real work of art.

Marker has also brought perspective to this story, so that it’s not just a nostalgic replay of protest marches. The immediate perspective is Vietnam, and here Marker begins with harrowing footage that pre-dates WikiLeaks’s release of audio revealing American helicopters mowing down civilians and even a journalist: We see and hear American bombers dropping bombs and Napalm on Vietnam, with the narration provided by one of the pilots, who could not be more excited than to be dropping napalm on “Vietcong” and seeing them flee their trenches into the open. He might be exulting over fireworks at a 4th of July picnic.

The bigger context is of course how most of these movements fit in with the larger dream of Communism, and its gradual erosion. Here “Le fond de l’air est rouge,” discouraging as it may be as an obituary for the movements of the ’60s, offers a ray of hope from the ashes, if I can mix my metaphors: Cynics like to say that the Movement des Indignes, or “Occupy” movement as it’s called in the U.S., doesn’t know what it wants. But in fact it’s the movement’s very freedom from a specific dogma that may be its salvation. Dogmas can be anchors, but they can also be anvils.

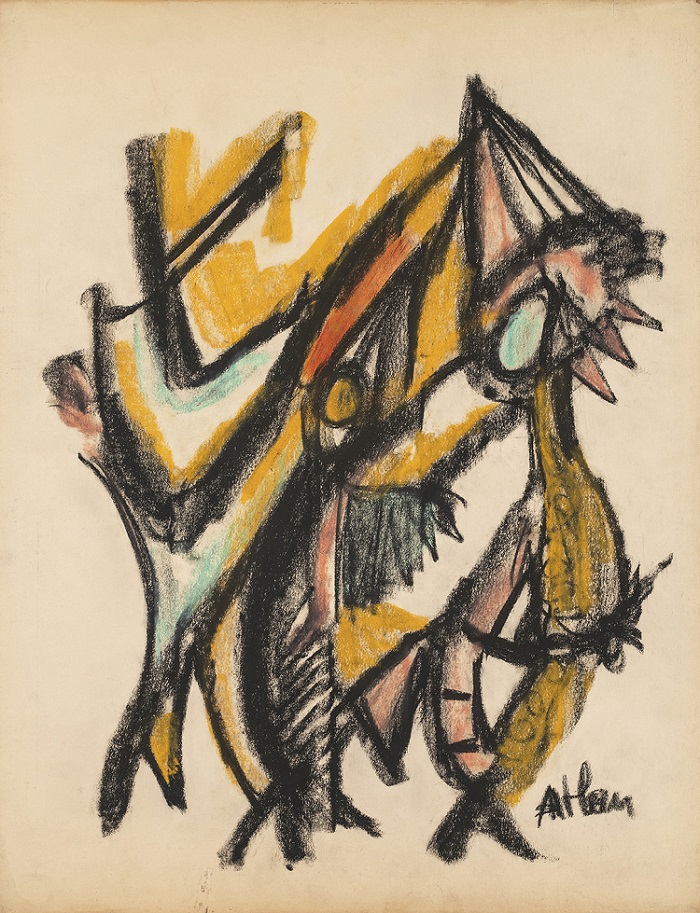

Often lost among the quarrel between the Abstracts and the Figuratives of the 1950s (and the critical partisans of their schools) was the achievement of work which — sometimes depending on the eye of the viewer — traversed both terrains. Thus it is no surprise that for an exhibition which by its name alone, Animal Totem, promises a degree of concreteness, the Galerie

Often lost among the quarrel between the Abstracts and the Figuratives of the 1950s (and the critical partisans of their schools) was the achievement of work which — sometimes depending on the eye of the viewer — traversed both terrains. Thus it is no surprise that for an exhibition which by its name alone, Animal Totem, promises a degree of concreteness, the Galerie  When an Anarchist meets the Avant-Garde in Paris et NY: From the exhibition Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde — From Signac to Matisse and Beyond, running October 16 through January 27 at the Orangerie in Paris (in a slightly neutered title: Les temps nouveaux, de Seurat à Matisse) and March 22 through July 25, 2020 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York: Henri Matisse, “Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading),” Paris 1905–06. Oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 23 1/2″ (72.7 x 59.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller, 1991. Photo by Paige Knight. © 2019 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

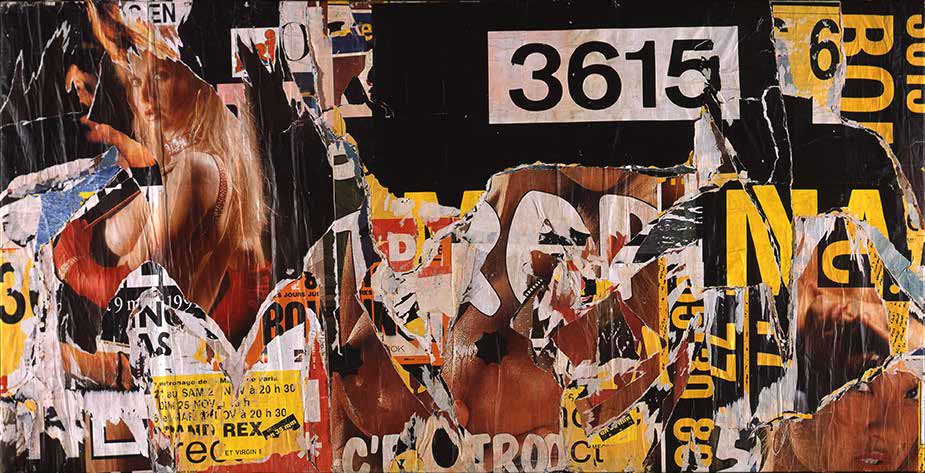

When an Anarchist meets the Avant-Garde in Paris et NY: From the exhibition Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde — From Signac to Matisse and Beyond, running October 16 through January 27 at the Orangerie in Paris (in a slightly neutered title: Les temps nouveaux, de Seurat à Matisse) and March 22 through July 25, 2020 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York: Henri Matisse, “Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading),” Paris 1905–06. Oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 23 1/2″ (72.7 x 59.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller, 1991. Photo by Paige Knight. © 2019 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.  It’s fitting that Jacques Villeglé — like the pioneer in the art of the lacerated street poster (and the modern French detective novel) Léo Malet in the 1930s, an inveterate street-walker — realized his final work in removing and re-constituting the posters for erotic “message boxes” on the Mintel (the French ancestor of the Internet) that began plastering the rues of Paris between 1989 and 1992, when posters became largely supplanted by billboards. “There’s a certain affinity between the artist and these modern Lorettes,” Harry Bellet writes for the catalog of the works’ exhibition, running through April 12 at the gallery Vallois in Paris. “Like (the subjects of the posters), he walked the streets…. He also has an admirable respect for them: They display themselves — or rather they’re plastered up. He unglues them, liberates them…. Sometimes he tears them up, certainly, but as he confided to Nicolas Bourriaud…, ‘A wounded visage is still beautiful.’ In fact, Villeglé hasn’t lacerated these women; he’s softly, tenderly, langorously but always lovingly blown the leaves away.” Above: Jacques Villeglé, “Route de Vaugirard, Bas-Meudon, April 1991,” 1991. Lacerated poster mounted on canvas, 152 x 300 cm. Copyright Jacques Villeglé and courtesy Galerie Vallois.

It’s fitting that Jacques Villeglé — like the pioneer in the art of the lacerated street poster (and the modern French detective novel) Léo Malet in the 1930s, an inveterate street-walker — realized his final work in removing and re-constituting the posters for erotic “message boxes” on the Mintel (the French ancestor of the Internet) that began plastering the rues of Paris between 1989 and 1992, when posters became largely supplanted by billboards. “There’s a certain affinity between the artist and these modern Lorettes,” Harry Bellet writes for the catalog of the works’ exhibition, running through April 12 at the gallery Vallois in Paris. “Like (the subjects of the posters), he walked the streets…. He also has an admirable respect for them: They display themselves — or rather they’re plastered up. He unglues them, liberates them…. Sometimes he tears them up, certainly, but as he confided to Nicolas Bourriaud…, ‘A wounded visage is still beautiful.’ In fact, Villeglé hasn’t lacerated these women; he’s softly, tenderly, langorously but always lovingly blown the leaves away.” Above: Jacques Villeglé, “Route de Vaugirard, Bas-Meudon, April 1991,” 1991. Lacerated poster mounted on canvas, 152 x 300 cm. Copyright Jacques Villeglé and courtesy Galerie Vallois. For Flowers for Valentine’s, running through March 16 at the Galerie Catherine Putnam at 40, rue Quincampoix in Paris, Frédéric Poincelet has curated a group show including work by Marc Desgrandchamps, Blutch, Ugo Bienvenu, and, above, David Hockney, “Sunflower I” (347), 1995. Engraving, 80 ex./ Arches 69 x 57 cm. Copyright David Hockneystudio. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

For Flowers for Valentine’s, running through March 16 at the Galerie Catherine Putnam at 40, rue Quincampoix in Paris, Frédéric Poincelet has curated a group show including work by Marc Desgrandchamps, Blutch, Ugo Bienvenu, and, above, David Hockney, “Sunflower I” (347), 1995. Engraving, 80 ex./ Arches 69 x 57 cm. Copyright David Hockneystudio. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.