“And if I shed a tear I won’t cage it

I won’t fear love

And if I feel a rage I won’t deny it.

I won’t fear love.”

— Sarah McLachlan

by Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

I see beauty everywhere.

Je voir de la beauté partout.

“And if I shed a tear I won’t cage it

I won’t fear love

And if I feel a rage I won’t deny it.

I won’t fear love.”

— Sarah McLachlan

by Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

I see beauty everywhere.

Je voir de la beauté partout.

First sent out by e-mail, and posted today for the first time. After getting more than half-way through with a re-edit seven months later, I’ve decided to leave this piece in its initial, raw, somewhat over-detailed initial state for the sake of authenticity… and for the record. — PB-I, October 23, 2019

PARIS — So there I was at dusk, heart broken and gums bleeding, teeth throbbing, staggering up the rue des Martyrs towards the Montmartre cemetery and the grave of the man I blamed it all on: Francois Truffaut.

In the late French director’s five-film, 20-year saga that began with the 1959 “The 400 Blows” and climaxed with “Love on the Run,” Antoine Doinel, played throughout the cycle by Truffaut’s alter-ego Jean-Pierre Leaud, is always on the run, often from the women in his life: His mother, his wife (the effervescent Claude Jade, whom Antoine, in the 1968 “Stolen Kisses,” rightly calls “Peggy Proper” for her prim manners), his girlfriend (Dorothee, who made her debut in “Love on the Run” and would go on to become the French equivalent of Romper Room’s Miss Nancy), his older married mistress (Delphine Seyrig at her glamorous apex), and various intermittent mistresses. The only one he seems to chase, apart from Dorthee’s “Sabine,” whom he loves but whose love seems to scare him (he found her after patching up and tracing a photo of the girl a supposed lover had torn up in a restaurant basement phone booth during an angry break-up call he overheard), is Marie-France Pisier’s “Colette,” who we first meet in Truffaut’s 30-minute contribution to the 1963 multi-director film “Love at 20.” (They encounter each other at a classical music concert; Antoine is working at the time in a Phillips record factory, with Truffaut letting us see the hot wax being spun into discs. In “Love on the Run,” Antoine finally tracks Dorothee’s Sabine to her work-place. A record shop where couples make-out in listening rooms.) You may remember Pisier as the vengeful sexpot in the movie adaptation of Sidney Sheldon’s “The Other Side of Midnight,” in which she introduces an inventive way of hardening an older man’s penis which might have come in handy in my own recent saga if I’d only have remembered it before now.

The first hint that I was starring in a sort of Bizarro universe re-make of, specifically, “Love on the Run” came when the woman in question — you know her as “Vanessa,” whom I described picking up on (although I’ve since learned that she may have been picking up on me) at a vernissage a few blocks from the Pere Lachaise cemetery (cemeteries also figure in the Antoine Doinel cycle; the Montmartre one where Truffaut was eventually buried turns up in three of the five films, notably as the burial place of Antoine’s mother, revealed to him by her former lover as being next to the real tomb of the model for “Camille.”) and right after having three teeth extracted, e-mailed me from the Lyon train station before boarding a train to that city to visit her grandkids (like Antoine, I seem to have unresolved mother issues) to tell me that the night, our first together which had concluded the previous morning, and which we’d both exuded at the time was extraordinary and unique (she’d e-mailed me afterwards that she didn’t understand why we weren’t still together) felt “incomplete” (later she’d call it “inaccomplished”) because I couldn’t or wouldn’t get it up. (My wording; she didn’t put it so vulgarly.) In the Truffaut film, after Colette calls him from a window on a Lyon-bound train at the Gare de Lyon, where Antoine has just dropped of his son for camp, Antoine jumps on the moving train without a ticket, surprises Colette in her sleeper car right after a fat middle-aged businessman, assuming she’s a prostitute, has rubbed up against her in the aisle (a lawyer, she’d spotted Antoine earlier in the day at the court-house, where with Jade he’d just completed France’s first no-fault divorce, an echo of my parents’ some years earlier). After they catch up, she upbraids him on the revisionist way he recounted their courtship as 20-year-olds in a fictionalized memoir he’s just published — “My family didn’t move in across the street from you, you followed us!” (At the time, Antoine is working as a proofreader at a – literally – underground publisher on a book detailing the 18 minutes when De Gaulle disappeared during the 1968 student-worker uprising. Letters requesting love assignations sent by underground pneumatics also figure in the 1968 “Stolen Kisses,” in this case from Antoine’s older, married lover – his employer’s wife — played by the glamorous Seyrig.) He tries to kiss her, she light-heartedly repels the attempt scolding him, “Antoine, you haven’t changed.” The conductor comes around for tickets, Antoine pulls the emergency chord and jumps off the still moving train. We see the now 34-year-old Antoine running across a field, an echo of the last, poignant, liberating moment in “The 400 Blows,” when a 14-year-old Antoine, having escaped from a youth home/prison, is frozen on screen and in our memories, a broad smile on his face as he runs on a beach, discovering the ocean (the antipathe of Chris Marker’s ocean in “La jete”) for the first time.

In my own Bizarro universe re-make of the Antoine-Colette train scene, it was Colette who, after having joined me in a mutually agreed upon and extraordinary kiss was jumping from our train.

I was devastated, as I thought we’d also both agreed that what made our first night together magical is that the things other couples often view as preliminary — hand-holding, snuggling, French kissing, hand-kissing — had for us been electric. (I’m purposely avoiding citing the many words and motions we exchanged which confirm this because this piece is not intended as an indictment – “If you don’t love me, what was this?”) After writing her an e-mail to ask why she chose to bring this up in an e-mail as opposed to face to face, and explaining that if you want your partner to get it up, the worse thing you can possibly do is tell him it bothers you that he couldn’t get it up, and that a 57-year-old man can’t just get hard on command, I said she should ask herself, “If he was impotent, would I continue with him?” and if the answer was no, get out. She misinterpreted this in a more dire manner, we made up Friday, but only for her to send me another e-mail Saturday — 20 minutes before she knew I was receiving guests, my artist friends K. & R. for the famous Palestinian and Jamaican chicken twins, breaking up. And adding if I wouldn’t mind returning the scarlet scarf her Islamophobic friend had left at my home after I asked her and her husband to leave a dinner part I’d hosted for them all when they started going at French Muslims. So it was with misty eyes that I opened the door to K. & R., and found myself confiding my troubles of the heart with friends with whom I’d not yet reached that level of intimacy. Thanks to their and particularly K.’s good humor — leading the conversation to other subjects but ready to go back to consoling me, even suggesting, “We need to find you a woman!” — I did pretty well, considering a germinating girlfriend had just broken up with me by e-mail. But I guess I must have sounded worse than I felt, because when I asked what I should do if she contacted me again, K. said “Drop it! Do you want to end up jumping out a window?!”

After more e-mail exchanges last week, the tenor of which from Vanessa remained mostly consistent — she was still running from the love express our train had become — I finally ceded, agreeing it was better to cut it off as I couldn’t return to the just-friends thing, she sent me an e-mail where she said that she too (as I’d expressed I was) was in tears, that her life had changed since “1/24” — the evening we met at the vernissage — that she’d never be the same again, that she knew she had a problem with loving, that she hoped I’d find someone but that it was probably too late for us.

This of course — the tears — brought me running, and I wrote her to say that I’d been blind, that she maybe thought she had a problem with love but that everything she’d done in my regard — particularly being ready to lose me — was done out of love.

On Friday we had another magical evening, organizing an impromptu, wintry pique-nique on the banks of the Ourcq canal. I assured her I wouldn’t go all out but just bring what was already in the house; as it happened this also included a vintage wooden unfoldable pique-nique table in a valise that came with the apartment. I’d promised her to go no further than a chaste kiss goodnight at the Metro station. “Vanessa and Paul, round two!” she’d blithely announced over the hummus, and the rest of the evening kept to this light tenor, with lots of laughter. At one point I stopped the converation to note: “This is important. You see? When we’re face to face, we understand each other. E-mail communication is really sinister.” The night concluded with a chaste kiss at the Metro.

Ghosts in the machine

Wanting to diversify my world — I’d be making my famous Palestinian chicken for friends of Vanessa and bringing it to the house they were moving to that day, looking out over (I’m not making this up) the Pere Lachaise cemetery — on Saturday morning I decided to check out the vernissage for a group exhibition in my suburban Paris village of the pre Saint-Gervais. Life is more than women! Life is more than the women in my life over the past few years who seem to be Bizarro Universe interpreting the scripts for Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel films!

After sensing that in lieu of the usual joy of discovery I still feel around art I was feeling incredibly wary after entering the art space, in the same room below the covered market where I’d scored my old aborted professor Jerome Charyn’s “The Catfish Man” — I was increasingly regretting that I lacked the coping skills Charyn’s hero (himself) had been inculpated with by being forced to tangle with the urban catfish in the mudflats of the Bronx of his come-uppance — when someone I didn’t recognize at first, a woman in her ’50s with a boyish hair-cut, rose up like one of Charyn’s catfish and announced in wonder, “Paul.” It was another V, the last girlfriend and who, in contrast to the current V., who never stopped blaming herself for being unable to love, had taken the opposite tactic with me when we last tango’d/tangle’d nearly three years ago, blaming it all on me, even though in this case the opposite was true; this was one sick puppy. I know this sounds like the usual break-up sour grapes, but I’m short-handing because she doesn’t merit more time than this. I simply mention the encounter because it may have been an omen….

… And to introduce what I conveyed to “Vanessa” as we marched from the ill-advisedly chosen Pere Lachaise rdv to the dinner at the home overlooking the cemetery. I know it’s not advised to mention an ex to a current, but for me this was a means of delivering a series of compliments:

“Where she doesn’t assume any responsibility, you unfairly blame everything on yourself…. And even though she’s 14 years younger than you, on looks there’s no contest.” Vanessa smiled widely at this. “She’s skinny-ass where you have the body of a woman, uninteresting to look at where you are.”

I was annoyed when …. No, I find I can’t go into what annoyed me, nor any other details of the party related to my interactions with “Vanessa” because it sounds like evidence gathering, and this piece is not intended to be an indictment nor a reckoning, but a first step on the path out — out of heartbreak and out of “Vanessa” — for myself. I also believe that, like an American black-belt I once knew in Antwerp once explained to me in saying why the very fact that his hands are deadly weapons means he has a reponsibility *not* to fight, a writer doesn’t have the right to use his considerable gifts in romantic reckoning.

So suffice to say that the evening seemed to end sublimely, with Vanessa and I getting lost in perpetual circling of a Paris roundabout, this one the Place Gambetta. We held hands from the moment we left the hosue; there was some warm French kissing. When I said I wanted her to come home with me, she responded that she “wasn’t against” this, but reminded me that she had to get up early to go meet her grand-daughter at the train station.

We seemed to part in joy hands taking an extra clutch before separating…

…but..not before, unprompted, she asked out loud again why she was unable to jump into my arms, then answered her own question with “Is it because you couldn’t get it up?,” though not putting it that way, again sorting the demon.

Once home, in a letter I sent on getting home at 1:30 a.m., I felt compelled to repeat my earlier answers, both the defensive and proactive ones: If you want a man to get it up, the worse thing you can do is tell him it bothers you when he can’t; and then detailing, explicitly, all the other ways I’d like to please her, and ending with, “Let’s have fun with it!”

In the last e-mail I sent her Sunday before she let the hatchet fall again (and once again by e-mail), I wrote, rather poetically (she completed the beauty and humor before lowering the ax), regarding our lost midnight turnabout, “I’d rather be lost with you than found with anyone else.”

Oh and I left out one important detail: After one embrace, I finally said the words in person for the first time: “Je t’aime,” with a big smile on my face. “What am I supposed to say?” “You’re not supposed to say anything, just accept it.”

I mention this because since she broke with me after the late Saturday night letters, I’ve been torturing myself with: Did the letters, particularly the lasciciousness, scare her away? What if I’d backed off – after the happy Metro separating – and allowed her the space to come to me. So to counter this self-torturing (I even mentioned this possiblity in my last letter to her – if I’d backed off, I might not have lost you) I’m trying to tell myself that it was more this first face-to-face declaration of love that did it.

Ultimately I think this is the problem, the reason that Sunday and Monday morning she pulled out, saying she was arresting the histoire d’amour with me because she wasn’t “at the hauteur” of my emotions and compliments to her, to a degree that it was making her sick: I don’t think she has a problem with loving (at one point she told me she’s never been able to love, that she ended her two marriages because of this); I saw this manifest from her towards me in copious ways over the past two plus weeks. I think she has a problem with accepting being loved.

Before starting this piece this overcast Tuesday morning, I’d determined not to read any new mails from V. because I knew if I read them I’d have to respond. (And that I shouldn’t have given her the power to confirm or deny that my letters, sentimental and lascivious, of late Satruday had scared her off.) The one I did receive from her this morning, sent last night, confirmed this urge but so far I’m resisting. Not so much because I’ve convinced myself that it’s unhealthy to continue on her roller coaster (I’ve left out the numerous things she’s said or acts she’s done which indicate a profound love because this is not intended to be a requisatory, but a first step towards my own healing .. and advancement / continuation in the search for the vrais amour) but because I’ve told the part of myself unable yet to fall out of love with her, unable to let go even though my brain and a large part of my heart realizes that this is unhealthy, to let myself be swallowed up by a heart that is really broken, that this is my last hope, I’ve decided to follow two precious pieces of advice dispensed to me by my New Zealand-bred horse chief on a pony farm along the Texas – Oklahoma border more than six years ago:

I don’t know if she’ll write me again. I don’t know if I’ll be able to keep from opening any mails she might send, or from responding if I do. But this is what I’m going to attempt, at least for a week. What I do know in my heart of hearts is that she’s hurt me so much with the ups and downs that it will take more than an e-mail to convince me of any change of heart that she might have, or rather return to the previous obsession she announced with me. I need her to do what she’d refer to as a “Woddy Allen,” running to me breathlessly along Fifth Avenue Woody at the end of “Manhattan,” arriving panting and breathless at my door before I move on.

But to get back to the French director towards whose whose grave I found myself staggering up the rue des Martyrs as the sun set over the Sacre Coeur church which slowly emerged above it, gums bleeding from the just-extracted tooth, heart still raw. Once at the grave, after filling my green plastic up from a nearby fountain with water and popping a dissolvable 1000 gram Paracetemol into the water, posing it on Truffaut’s grave (decorated with an unravelling 35 MM film spool and a worn photo of Truffaut, Leaud, and a woman who might have been Claude Jade on the set)and watching it fizz away like this love affair, I lifted the glass and, echoing the Charles Trenet song which provides the theme for the 1968 “Stolen Kisses” – in which Leaud’s Antoine and Jade’s Christine fall in love – toasted Francoise Truffaut with “A nos amours,” to our loves. I might have added “This is all your fault,” for setting a model of Antoines and his women I was continuingly trying to counter-act. I wanted to be the anti-Antoine, proposing a definite “OUI!” to all these French women I was encountering. Why did they keep behaving like Truffaut’s Antoine, falling in love only to deny it and jump off the train, fleeing into the great French wilderness, fleeing love – mine and theirs – on the run?

From “Manet and Modern Beauty,” opening at the Art Institute of Chicago May 26 and the Institute’s first homage to Édouard Manet in more than 50 years: Édouard Manet, “In the Conservatory,” circa 1877–79. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

From “Manet and Modern Beauty,” opening at the Art Institute of Chicago May 26 and the Institute’s first homage to Édouard Manet in more than 50 years: Édouard Manet, “In the Conservatory,” circa 1877–79. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

“If Ragon’s erudition is immense, it has always been irrigated by the blood and misery of real life.”

— François Nourissier

By and copyright Michel Ragon

Translation copyright Paul Ben-Itzak

Reflecting the author’s popular roots, Michel Ragon’s 1956 “Trompe-l’oeil” is less an easy parody of the nascent contemporary art market than an introduction to the complex Abstract Art universe disguised as tragi-comic spoof, with contemporary swipes at corrupt art critics and mercenary art revues à la Balzac’s “Lost Illusions.” (It also offers a trenchant commentary on anti-Semitism.) Ragon’s colorful fictional personnages interact with some of the real-life artists of the era that he, as a critic and curator, championed (à la Zola). To read an excerpt of Michel Ragon’s “La Mémoire des vaincus” (The Book of the Vanquished), click here.

In the très chic Parisian salon of Monsieur Mumfy — the very same Mumfy of the celebrated underwear ads — “with Mumfy, you’re always comfy” — a Family Conference was underway. The plethora of Plexiglas and the multitude of apertures in the porous Oscar furniture eliminated any idea of intimacy in the vast square room, whose walls were ornamented with a collection of Klees. The quality of these paintings had earned their proprietor the high regard and hosannas, frequently expressed, of the leading art critics of Paris as well as art aficionados.

Ensconced in a tubular arm-chair held together with cream-colored cords which leant it the vague allure of a warped harp, Monsieur Mumfy was in the process of interrogating his son, standing before him. Slightly separated from them, but still participating in the conversation, Madame Mumfy was busy at a black ceramic table creating a more or less Cubist collage. It was not that Madame Mumfy was an artist, or even trying to pass as one, but that she liked to distract herself with cutting up colored paper and re-assembling it, sometimes à la Picasso, sometimes à la Matisse, just as 50 years earlier she might have devoted herself to needlework.

“My dear Charles,” Monsieur Mumfy declared, “it’s time to decide. You’ve now graduated from high school; it’s time to pick a career. We’re here to help….”

Charles, clad from head to toe in black, his stiff hair combed over his forehead à la Bourvil (or à la Marlon Brando), pulverizing his handkerchief between his nervous fingers, tentatively stepped forward before retreating, with a certain dandy-ness that might have lead one to suspect an inclination towards sexual inversion, but it was nothing like that. Charles’s effeminate affectations, like his bird-like hopping back and forth, his juvenile gestures, and the weaving of his hips when he walked, were à la mode.

“Respond, Cheri!” chimed in Madame Mumfy. “Don’t let your father just languish there. Otherwise we’re in for another 24 hours of stress!”

“Okay Pops, Moms,” Charles finally decided, accentuating his dandy-ness. “My dream is to become… a notary public.”

Madame Mumfy precipitously dropped her scissors and glue to rush to the side of her husband, who had begun to hyperventilate. Striking him on the back and tapping him on the cheeks, she tried to reassure him:

“It’s nothing, darling, nothing! Charles is obviously kidding….”

When Monsieur Mumfy had recovered his wits, his son, worried by the turn of events, repeated, all the same:

“I don’t want to make you mad Pops, Moms, but I’m not joking: I really want to be a notary public.”

Monsieur and Madame Mumfy glanced at each other with a complicit air tempered by indulgence. Then Monsieur Mumfy responded with a firm voice:

“My dear Charles, don’t be ridiculous. No one becomes a notary public these days. How could such an idea ever have sprouted up in the head of a MUMFY?! Choosing to be a notary public. The very idea! Does one choose to be a cuckold? Haven’t you read Balzac? Flaubert? For more than a hundred years notary publics have been looked at as grotesque characters, the butt of jokes — and your “dream” would be to sport a black skull-cap and bifocals with a pocket-watch hanging on a chain over a protuberant stomach that — thank God — you’re not even close to acquiring. Becoming a notary public might be fitting for the son of a country school-teacher, but you, Charles — do you want to be the shame of your family?

“Come, come now — it’s just the silly fancy of an adolescent. I’m going to help you…. I’ve got it! What if you became an artist…? A painter, for example?”

“But Pops, I don’t know how to paint.”

Monsieur Mumfy clutched his head between his hands in a sign of total exasperation in the face of such naïveté.

“Look at this blockhead! You’ll learn, Charles, you’ll learn! Does someone refuse to become a doctor because he’s never applied a bandage? One learns to paint, my boy, as with anything. And consider the future in painting. Picasso is a millionaire, as is Matisse…. Have you ever heard of a notary public who, starting out from scratch, has carved out such a shining success? Picasso lost so much time, in his youth, because he was poor, and couldn’t afford paints or canvasses, and didn’t know any dealers or critics. But you, Charles, won’t lack for anything. I’ll give you a monthly allowance so you won’t have anything to worry about. You can take advantage of my connections as a collector. With a little effort from you, my boy, we’ll make a famous artist out of you, who will be the pride and joy of the family. Look at Ancelin. He also wouldn’t have heard of becoming a painter. He wanted to be an officer, on the pretext that his father is a general. But General Ancelin talked him out of pursuing a career in a field compromised by the pacifism that’s more and more in vogue these days. He also, our old friend Ancelin, was able to see the opportunities available these days in the art world. And Ancelin now has a contract with Laivit-Canne’s gallery and will soon be exposed in New York.

Rising heavily, Monsieur Mumfy bumped his head against one of the blades of a Calder mobile rotating from the ceiling. He scooted it away distractedly with the back of his hand, as if it were a fly. The mobile started to undulate, with all its branches revolving in silence. It was as if a giant insect had suddenly come to life above the father and son, oblivious to its awakening. A soubrette entered, after knocking, apparently in the throes of panic.

“Madame, the pottery set that Monsieur gave Madame….”

“Yes…?

“I don’t know how it happened, but it’s… bleeding.”

“Now now, explain yourself clearly and don’t get upset,” sighed Madame Mumfy, delicately snipping a strip of embossed paper.

“Yes, Madame. I went to serve the consommé

in the pottery bowls and the consommé turned completely blue.”

“WHAT?!” erupted Monsieur Mumfy. “Who told you to touch that pottery?! You couldn’t tell that those plates were not made to be eaten from?!”

“Then what are they made for, Monsieur?” asked the maid, flustered.

“They’re not ‘made’ for anything!” roared Monsieur Mumfy even louder, so loud that the Calder began to hiccup. “Those plates are works of art. One does not eat from works of art. One beholds them!”

The maid tried to defend herself by babbling, “I wouldn’t have thought of pouring consommé on Monsieur’s paintings. I just thought that bowls are bowls….”

Monsieur and Madame Mumfy broke into simultaneous laughter, bursting out, “She believed that bowls were bowls…!” “Incredible!” “We must tell Paulhan about this!”

The maid departed, clearly vexed. By the immense bay window looking out over the Luxembourg Gardens, Charles, indifferent to the fit of laughter which had seized his parents, gazed nostalgically at the Law School.

***

Monsieur Mumfy was not a born art collector. Before the war, consumed as he was with his underwear factory, he didn’t even know that painters existed. It took an accident. One of his debtors brought him a batch of watercolors, gouaches, and paintings by an unknown German artist, pleading with him to accept the paintings as collateral. Monsieur Mumfy initially refused this singular arrangement. Since when did one trade underwear for paintings?! But the debtor had been driven to ruin. Ahead of taking him to court, Monsieur Mumfy had the paintings stored in one of his warehouses, without taking the trouble to even look at them. Some months later, the debtor committed suicide. Monsieur Mumfy had the paintings brought up so he could study them to see if by chance they might actually be worth something. Stupefied, he discovered that they were replete with child-like doodles — all sorts of rivers, of birds, of funny figures. He’d been had. He began to choke with rage. The bastard had conned him before offing himself! Just in case, though, he asked an art dealer to take a look; the dealer refused to buy anything, smiling snidely.

From the Arts Voyager archives: Paul Klee, Untitled, 1939. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

From the Arts Voyager archives: Paul Klee, Untitled, 1939. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

“So I can throw them in the garbage,” Monsieur Mumfy fumed.

“Oh,” the dealer answered, with an evasive gesture, “hang on to them all the same. You never know. If you have the space….”

Immediately after the war, the very same dealer came back to see Monsieur Mumfy, who’d completely forgotten the painting fiasco. He offered him $5,000 for the whole lot of Klee works that he recalled seeing earlier.

Faced with the enormity of the amount (the debtor owed him, before the war, a little over $500), Monsieur Mumfy became suspicious, asked other dealers to come look at the paintings, and got offers of $7,500, $10,000, and $12,500 for the Klees…. He decided to read a few books about contemporary art, discovered that the market for paintings was the most speculative around, and that Klee was considered in America to be a major painter. He bought ornate frames for his paintings and had them hung in his salon. Before long, there were requests to photograph ‘his’ oeuvres, and to reproduce them in color in luxury magazines and art books. The name Mumfy was evoked wherever there was talk of Klee’s oeuvre. Thus he was catapulted, almost unconsciously, into the midst of the world of arts and letters and readily let himself be converted to all things avant-garde. He allowed himself to indulge in the luxury of philanthropy, underwriting several art revues and sponsoring young artists whose paintings resembled Klee’s. He was even recognized as one of the premiere Klee specialists in France. Far from making him lose money, the arts earned him notoriety he’d never even dreamed of as a simple garmento. He was decorated for services rendered to the arts. Famous artists cultivated his friendship. Even his fellow industrialists now showed him a deference that they’d never have dreamed of according him before he earned a reputation as an “influential collector.” Monsieur et Madame Michaud wanted to be up-to-date. They bought an apartment that they hired Le Corbusier to transform. Nothing, absolutely nothing in their home pre-dated the 20th century (with the possible exception of its proprietors).

Brought up amongst this architecture of pure lines, blasé about being surrounded by furniture which constantly reminded him of a dentist’s office, exhausted by this daily frequenting of chefs-d’oeuvre, Charles began to fantasize about living in a dusty bureau, with large old straight-legged wooden arm-chairs, an oak desk and an ink-well with a feather plume. This was his own form of poetry. To every teenager his folly.

*In English in the original.

Original French language text of excerpt, by Michel Ragon:

Dans le salon très moderne de Monsieur Michaud, le fameux Michaud des sous-vêtements du même nom (« avec Michaud, toujours chaud »), se tenait une réunion de famille. L’abondance du plexiglas et les multiples ouvertures des meubles Oscar enlevaient toute intimité à cette vaste salle cubique dont les murs s’ornaient d’une collection de peintures de Klee. Leur qualité valait à son propriétaire l’estime et la considération, très souvent exprimée, des meilleurs écrivains et amateurs d’art.

Assis dans un fauteuil tubulaire tendu de cordes blanches qui lui donnaient une vague allure de harpe faussée, Monsieur Michaud interrogeait son fils, debout devant lui. Un peu à l’écart, mais participant toutefois à la conversation, Madame Michaud s’occupait à un collage relativement cubiste sur une table de céramique noire. Non pas que Madame Michaud fût artiste, ni même qu’elle tentât de passer pour telle, mais elle se distrayait en découpant des morceaux de papiers de couleurs et en les assemblant, tantôt à la manière de Picasso, tantôt à la manière de Matisse, comme elle se fût donnée, cinquante ans plus tôt, aux points de canevas.

— Voyons, Charles, disait Monsieur Michaud à son fils, décide-toi. Tu viens d’être reçu a ton bac, il te faut t’orienter vers une carrière. Nous sommes là pour t’aider…

Charles, tout de noir vêtu, les cheveux raides ramenés sur le front à la Bourvil (ou à la Marlon Brando), triturait son mouchoir, avançait une jambe, la reculait, avec un dandinement pouvant faire supposer qu’il tendait à l’inversion sexuelle, mais il n’en était rien. L’allure efféminée de Charles, comme ses sautillements, ses gestes gamins, sa démarche déhanchée, appartenait au style de l’époque.

— Réponds, Amour, s’exclama Madame Michaud, ne laisse pas languir ton père ; sinon il va encore nous faire vingt-quatre de tension!

— Voila, pap’, mam’, se décida enfin Charles, en accentuant son dandinement, moi j’aimerais bien devenir notaire.

Madame Michaud abandonna précipitamment ses ciseaux et sa colle pour courir à son mari qui suffoquait. Elle le frappais dans le dos avec énergie, lui tapotait les joues :

— Ce n’est rien, darling*, ce n’est rien ! Charles plaisante, tu le vois bien…

Lorsque Monsieur Michaud reprit « ses esprits », Charles très ennuyé par la tournure des événements, redit quand même :

— Je ne voudrais pas vous fâcher, pap’, mam’, mais c’est vrai : j’aimerais bien être notaire.

Monsieur et Madame Michaud se regardèrent d’un air entendu et indulgent. Puis Monsieur Michaud dit d’une voix ferme :

— Mon petit Charles, tu es ridicule. On n’est plus notaire, de nos jours. Comment une pareille idée a-t-elle pu se nicher dans la tête du fils Michaud ! Choisir d’être notaire… Est-ce que l’on choisit d’être cocu ? Enfin, quoi, n’as-tu pas lu Balzac ? Flaubert ? Depuis cent ans les notaires sont des personnages de farce et ton idéal serait de coiffer la calotte noire, de porter des bésicles et une chaîne de montre en or sur un ventre que, Dieu merci, tu n’es pas encore près d’acquérir. Le métier de notaire peut, à la rigueur, convenir à un fils d’instituteur de campagne ; mais toi, Charles, veux-tu faire honte à ta famille ?

« Allons, allons, c’est une bêtise de jeune homme. Je vais t’aider, moi. Tiens… si tu faisais une carrière d’artiste… Peintre, par exemple ?

— Mais, pap’, je ne sais pas peindre…

Monsieur Michaud se prit le crâne à pleines mains, en signe de découragement total devant une telle innocence.

— Regardez-moi ce grand sot ! Mais tu apprendras, Charles ! Est-ce qu’on refuse d’envisager la médecine parce qu’on n’a jamais fait un pansement ! La peinture s’apprend, mon petit, comme toute chose. Et regarde l’avenir qui est offert à un peintre. Picasso est milliardaire, Matisse aussi… Connais-tu un notaire qui, parti de rien, soit arrivé à une aussi brillante situation ? Picasso a perdu beaucoup de temps, dans sa jeunesse, parce qu’il était pauvre, qu’il ne pouvait pas s’acheter de couleurs ni de toiles, qu’il n’avait aucune relation parmi les marchands et les critiques. Mais toi, tu ne manqueras de rien. Je te donnerai une mensualité qui te laissera la tête libre. Tu profiteras de mes relations de collectionneur. Allez, fiston, avec un pu de bonne volonté de ta part, nous ferons de toi un artiste célèbre, qui sera la joie de la famille. Regarde Ancelin, il ne voulais rien savoir pour être peintre, lui non plus. Il voulait devenir officier, sous prétexte que son père est général. Mais le général Ancelin a bien su le dissuader de suivre une carrière aussi compromise par ce pacifisme de plus en plus en vogue. Lui aussi, ce vieil ami Ancelin, avait su voir quels débouchés offrait maintenant le monde des arts. Ancelin a son contrat chez Laivit-Canne et il va bientôt exposer a New York.

En se relevant lourdement, Monsieur Michaud heurta du front une pale d’un mobile de Calder qui se balançait dans la pièce. Il la chassa distraitement du revers de la main, comme une mouche. Le mobile se mit à onduler, toutes les branches évoluèrent en silence. On eût dit qu’un gigantesque insecte se fût tout à coup éveillé au-dessus du père et du fils qui n’y prenaient garde. Une soubrette entre, après avoir frappé. Elle paraissait affolée :

— Madame, le service de céramique que Monsieur avait offert à Madame…

— Et bien ?

— Je ne sais pas comment cela a pu se produire, mais il déteint.

— Expliquez-vous clairement et ne vous énervez pas, soupira Madame Michaud en coupant délicatement une languette de papier gaufré.

— Oui, Madame, j’ai voulu servir le consommé dans le service en céramique et le consommé est devenu tout bleu.

— C’est insensé, hurla Monsieur Michaud. Qui vous a dit de toucher à ce service ! Vous n’avez donc pas vu que ces assiettes n’étaient pas faites pour manger dedans !

— Alors elle sont faites pour quoi, Monsieur, demanda la bonne, ahurie.

— Mais pour rien, hurla encore plus fort Monsieur Michaud, si fort que le Calder en eut des hoquets. Ces assiettes sont des œuvres d’art. On ne mange pas dans des œuvres d’art. On les regarde !

La bonne essaya de se justifier en bougonnant :

— Je n’aurais jamais pensé verser du consommé dans les tableaux de Monsieur. Mais je croyais que des assiettes étaient des assiettes…

Monsieur et Madame Michaud éclatèrent de rire en même temps. Ils pouffaient : « Elle croyait que les assiettes étaient des assiettes… C’est à ne pas croire ! Il faudra raconter ça a Paulhan. »

La bonne repartit, vexée. Par l’immense baie vitrée qui donnait sur le Jardin du Luxembourg, Charles, indifférent a la crise de fou rire de ses parents, regardait avec nostalgie vers la Faculté de Droit.

***

Monsieur Michaud n’était pas né collectionneur. Avant la guerre, tout occupé à son industrie de sous-vêtements, il ignorait même qu’il existait encore des peintres. Il avait fallu un hasard. Un de ses débiteurs lui apporta un lot d’aquarelles, de gouaches et de peintures d’un artiste allemand inconnu, en le suppliant de les conserver comme gage. Monsieur Michaud refusa d’abord ce singulier marché. Depuis quand échange-t-on des sous-vêtements contre de la peinture ! Mais le débiteur était acculé à la ruine. En attendant d’entamer des poursuites, Monsieur Michaud fit porter dans une de ses remises toutes ces peintures qu’il ne prit même pas la peine de regarder. Quelques mois plus tard, son débiteur se suicida. Monsieur Michaud se fit apporter les peintures afin d’examiner s’il pourrait en tirer quelque argent. Stupéfait, il vit qu’il s’agissait de choses enfantines, des sortes de fleuves, d’oiseaux, de bonshommes. Il s’était fait bien avoir. La fureur l’étranglait. Ce salaud de machin s’était payé sa tête avant de se suicider. A tout hasard, il fit quand même venir un marchand qui refusa d’acheter en souriant d’un air supérieur.

— Alors, je peux les foutre à la poubelle, suffoqua-t-il.

— Oh, dit le marchand, avec un geste évasif, gardez-les toujours. On ne sait jamais. Si vous avez de la place…

Peu après la guerre, ce même marchand revint voir Monsieur Michaud qui avait complètement oublié cette histoire de peintures. Il lui offrit deux millions pour ce lot d’œuvres de Klee qu’il se souvenait avoir vu autrefois.

Devant l’énormité de la somme (le débiteur ne lui devait, avant la guerre, que quelques centaines de mille francs), il se méfia, fit venir d’autres marchands de tableaux qui lui offrirent trois, quatre, cinq millions… Il se mit alors à lire quelques livres sur l’art contemporain, découvrit que la peinture était la marchandise la plus spéculative qui soit et que l’on considérait Klee, en Amérique, comme un grand peintre. Il fit encadrer luxueusement ses peintures et les accrocha dans son salon. Bientôt, on lui demanda l’autorisation de photographier « ses » œuvres, de les reproduire en couleurs dans des revues luxueuses et des livres d’art. Son nom fut mentionné à chaque fois que l’on parlait de l’œuvre de Klee. Il pénétra ainsi, à son insu, dans le monde des arts et des lettres et se laissa aisément convertir à toutes les avant-gardes. Il se paya le luxe d’être parfois philanthrope, de subventionner quelques revues, d’encourager quelques jeunes artistes dont la peinture ressemblait à celle de Klee. Il arriva même à passer pour l’un des premiers spécialistes de Klee en France. Loin de lui faire perdre de l’argent, les arts lui apportaient une considération qu’il n’avait jamais obtenue en tant qu’industriel. On le décora pour services rendus aux arts. Des artistes célèbres recherchèrent son amitié. Même les autres industriels lui témoignaient maintenant une déférence qu’ils n’auraient jamais eu l’idée de lui accorder avant qu’il devînt un « grand collectionneur ». Monsieur et Madame Michaud voulurent être à la page. Ils achetèrent un appartement qu’ils firent transformer par Le Corbusier. Rien, absolument rien chez eux, ne fut antérieur à ce siècle, si ce n’étaient eux-mêmes.

Elevé dans cette architecture aux lignes pures, blasé du mobilier qui lui rappelait fâcheusement le cabinet du dentiste, abruti par la fréquentation journalière des chefs-d’œuvre, Charles se prit à souhaiter vivre dans une étude poussiéreuse, avec de grandes vielles chaises aux pieds droits, en bois, avec un bureau en bois et un porte-plume avec une plume. C’était sa poésie, à lui. A chaque adolescent sa folie.

Excerpted from “Trompe-l’œil,” by Michel Ragon, published in 1956 by Éditions Albin Michel, Paris, and copyright Michel Ragon.

By Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2019 Paul Ben-Itzak

“You are the light of the world

But if that light’s under a bushel

It’s lost something kind of crucial.”

— “Godspell”

(Like what you’re reading? Please let us know by making a donation so that we can continue this work. Please designate your PayPal donation to paulenitzak@gmail.com , or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check. To read this article in French or any other language, just click the translation button at the right.)

PARIS — For personal reasons, I’ve resolved this week to get out more and circulate: to try to connect with people, with the esperance that the ame-soeur, the soul-mate, is waiting for me somewhere among them. (If you’re also looking, click here to find out more about me — and the us I’m looking for.) So after a moderately successful noon-time Russian Earl Grey thermos tea on the banks of the mighty Ourcq canal here in Pantin / le pre Saint-Gervais — there was the water but there was also the bruit of the garbage truck which seemed to be following me around, and the blight of the gray Centre National de la Danse behemoth which looks more like a prison than bunhead central — last night I was determined to have at least one coffee at Le Danube, a brightly-lit, recoup-furnished pastel colored bar on the place of the same name dominated by a buxom lime-stone babe that I’ve had my eyes on (the bar, not the babe) since attending a vide-grenier (community-wide garage sale; vide = empty, grenier = attic) and activities fair in the ‘hood nearly five years ago. Before that, I planned to watch the sunset and the people jogging and returning from work from a bench high atop the Buttes Chaumont park, my ears caressed by its water-falls and my chest warmed by more Russian tea, moderated with Algerian mint left over from Saturday’s Palestinian and Jamaican chicken twins feast with my Bellevilloise artiste friends K & R. I’d never liked this man-made park, designed by Colonel Hausmann and just as antiseptic as his apartment buildings, with the clumps of cypress trees divided by a concrete periphery path whose connecting trails never seem to lead to the lake at the bottom… until I started translating Michel Ragon’s “La Mémoire des vaincus” (The Book of the Vanquished), in which the young street urchin heroes, who’ve just been taken in by two almost as young publishers of an anarchist journal at the same time they’re hosting members of the violent Bonnot Gang, regal in cavorting amongst the caves and falls before running down to the La Villette Basin. Ragon and his wife Françoise have become my model couple since I met them Saturday afternoon, her nudging her older husband on observations they’ve shared and developed together for 51 years, since getting married in a building constructed by Le Corbusier, a Ragon chou-chou. (Ragon told me he switched to architecture after art magazines, pressured by advertisers, started trying to clamp down on what he could and couldn’t write. When the same thing started happening at the architecture magazines, he turned to books.)

Besides the thermos, the chick — er, soulmate — attracting tools I brought with me were the copy of Ragon’s “Dictionary of Anarchism” M/M gave me (they also gave me, as I was hoping for, a copy of his “Courbet, Painter of Liberty”) and my two vintage ping-pong paddles. (They’re not vintage because I bought them in a vintage store, they’re vintage because I’ve had them since 1973, when I came in second in the city-wide San Francisco championships for the 9-12 age group, having won my ‘hood and my region before getting slaughtered by a nine-year-old Chinese kid half my size whose spin-balls I couldn’t touch. I’ve had the paddles as long as I’ve had this adult carcass, and they’re in a lot better shape.)

Would you play ping-pong with this man? (Photo: Julie Lemberger.)

I’d decided to pack the paddles for this Paris trip after seeing Forest Gump for the first time; stacked on top of the tiny valise he brings with him when he goes to retrieve his childhood sweetheart is a paddle. And after a twilight spotting from a bridge off the Ile St-Louis of a pair of kids playing in the Tino Rossi sculpture park on the Left Bank, I’ve got it into my head that maybe the first step to finding my soul-mate is finding a playmate. At first the idea was to sit on a bench near a table with the rackets until she showed up. But lately I’ve been thinking that instead of going where the ping-pong players are — which might just lead to another shellacking by a tiny Chinese kid — I might have better luck, soul/playmate-wise, taking my paddles to where the chicks hang out, brandishing my most innocent Tom Hanks smile (being careful not to open my mouth too widely, at least not until the denture arrives), and attracting the French nana with the innocent abroad thing, hoping I’ll do better than Lambert Strether in Henry James’s “The Ambassadors,” whose innocence is ultimately quashed by European cynicism and hundreds of years of European history. (I’ve been hearing the rebuff Strether’s French lass handed him since an Italian boy told me just after high school, “To understand my sister, you first need to understand our history,” an imposing wall for someone who keeps trying to act like he was born yesterday.)

The tea proved edifying, but — initially anyway — not in the way I’d hoped for.

The last time I took a twilight tea in this spot, I’d been moved by the sight of a young couple who paused at the bench next to me so the man could take the baby-pack from the woman. This time I was devastated by the arrival of a boy in a light blue cap tossing a squeaky ball to a beagle, accompanied by a big man in an olive jacket and darker blue cap who, instead of marveling at this precious moment which will never happen again, remained riveted to his cell-phone screen. I got the impression that if the beagle weren’t there, I could kidnap the kid — perhaps by using the ping-pong paddles as a lure — and the father would keep right on staring at his screen. “Go play with the other dog,” the kid said, as he finally wrenched the squeaky-toy from the beagle’s jaws while his father remained oblivious. “We’ll play with the ball more at home.” I followed them with my eyes another 100 yards until they passed through the iron gate, the distance between the father and son growing.

Things perked up for my own family prospects when a tall and lithesome young woman, perhaps in her thirties, her short curly hair ensconced in a dark brown cap, took a look at me surrounded by all this regalia, hot steaming chrome cup of tea at my lips, paddles by my side, anarchists in hand, and, albeit without slowing down much, spread out her arms and, looking at me in the eyes, smiled as if to proclaim, ‘On est bien la, n’est pas?!,’ to which implicit benediction I responded out loud, “Tranquille.” (Not a worry in the world.)

When it finally got too dark to tell the Christian anarchists from the anarcho-syndicalists from the Action Française anarchists (Ragon lays out five distinct categories in an introduction that’s the most concise sweeping history of anarchism I’ve ever come across), after beholding the layered cushions of the Sun setting over Northeastern Paris I left the park and headed down the street to the Danube, telling myself, “Your sole goal tonight is to buy one coffee. If you do that, the evening will be a success.” But when I looked in at the bar and saw there were just two guys with the requisite five-o’clock shadows seated on leather stools chatting with two crew-cut male bartenders, I decided that there wasn’t any point if there were no women in sight. On the off-chance that She might simply be running late, I decided to walk around the block, hoping that no one would wonder what a swarthy unshaven guy in a dark trenchcoat and “I Heart Golf” beret was doing loitering in the area with a pair of Chinese ping-pong paddles and an anarchist dictionary, and call the “I just saw something suspicious” hotline.

When I returned to the bar, the counter-composition hadn’t changed, and it looked like the chercher la femme playmate crusade would come up empty for the night. But all was not for naught, as I did find a good closer for this column: Looking through the glass at the bright interior of the restaurant to give it a final scoping out before leaving, I spotted, sitting alone at a table — whose neighbor table was free — a woman who resembled either Camille Puglia, Gloria Emerson (the Vietnam war correspondent who’d once chided me in an airport jitney from Princeton to JFK, after I’d bragged that I was already writing for the NY Times at 23, “When David Halberstam was 23 he already had his first Pulitzer”), or my high school advanced composition professor Anne-Lou Klein, looking up towards the heavens as if exasperated by the book in front of her:

“L’Homme Nu.” (The Naked Man.)

C’est moi — comme tu le savez bien, dear reader.

PS: As for my ping-pong paddle as chick magnet theorem: Usually when I smile at a woman on the street here in Paris she just ignores me or grimaces. But as I was crossing the street from the Danube to the avenue General Brunet, paddles clearly in evidence, a young woman who registered Amelie on the light in the eyes scale looked at me and coyly smiled with a glint in her eye, a smile inviting enough to make me want to live to love another day.

I’ve often wondered: If an alien looked down on us, what would he see? At this moment on the streets of Paris, an awful lot of people talking into little boxes or who simply seem to be talking to themselves, ignoring their prochaine to pummel their box with their fingers. Until the aliens arrive, we can count on artists to give us a clairvoyant perspective on this society increasingly depourvu de la contacte humaine. So if you can get away from your little box and lift your eyes long enough to negotiate the narrow labyrinthine rues of the Marais, the above oeuvre by Catherine Balet, “Moods in a Room #34 (2019),” as well as other works by the hybrid artist pastiching painting and photography to investigate contemporary mores, is on view through March 30 at the Galerie Thierry Bigaignon at 9 rue Charlot. (Chaplin — or Charlot as the French call him — no doubt someone else who might have had something to say about the zombies walking the streets with their heads in the cyber-sand.) Courtesy Galerie Thierry Bigaignon. — Paul Ben-Itzak

I’ve often wondered: If an alien looked down on us, what would he see? At this moment on the streets of Paris, an awful lot of people talking into little boxes or who simply seem to be talking to themselves, ignoring their prochaine to pummel their box with their fingers. Until the aliens arrive, we can count on artists to give us a clairvoyant perspective on this society increasingly depourvu de la contacte humaine. So if you can get away from your little box and lift your eyes long enough to negotiate the narrow labyrinthine rues of the Marais, the above oeuvre by Catherine Balet, “Moods in a Room #34 (2019),” as well as other works by the hybrid artist pastiching painting and photography to investigate contemporary mores, is on view through March 30 at the Galerie Thierry Bigaignon at 9 rue Charlot. (Chaplin — or Charlot as the French call him — no doubt someone else who might have had something to say about the zombies walking the streets with their heads in the cyber-sand.) Courtesy Galerie Thierry Bigaignon. — Paul Ben-Itzak

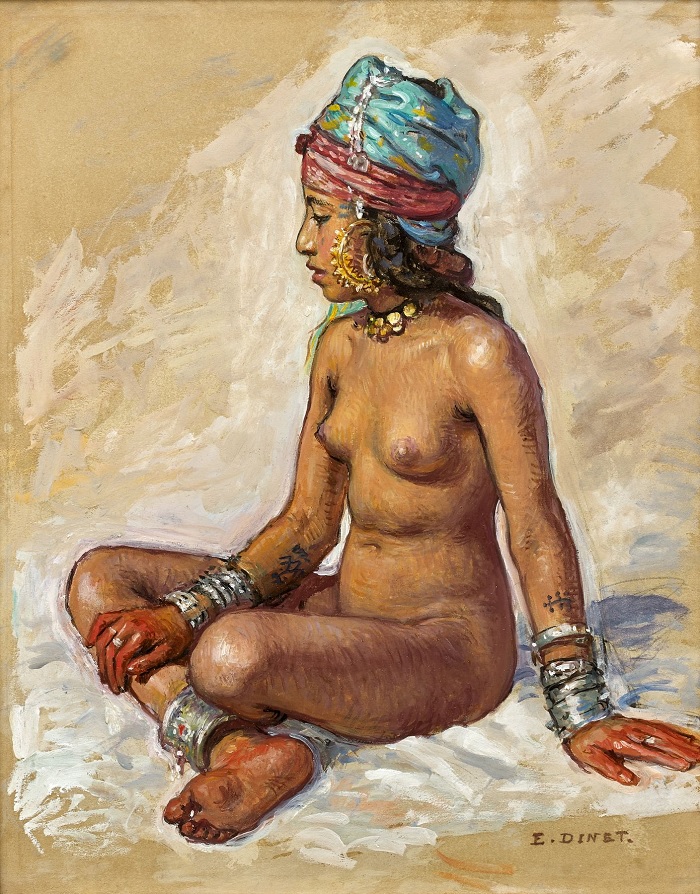

From the Arts Voyager / Art Investment News Archive: Étienne Dinet, “Baigneuse.” Image courtesy and copyright Artcurial. Born Paris, in Étienne Dinet (1869 – 1829) spent much of his life in Algeria and converted to Islam.

From the Arts Voyager / Art Investment News Archive: Étienne Dinet, “Baigneuse.” Image courtesy and copyright Artcurial. Born Paris, in Étienne Dinet (1869 – 1829) spent much of his life in Algeria and converted to Islam.