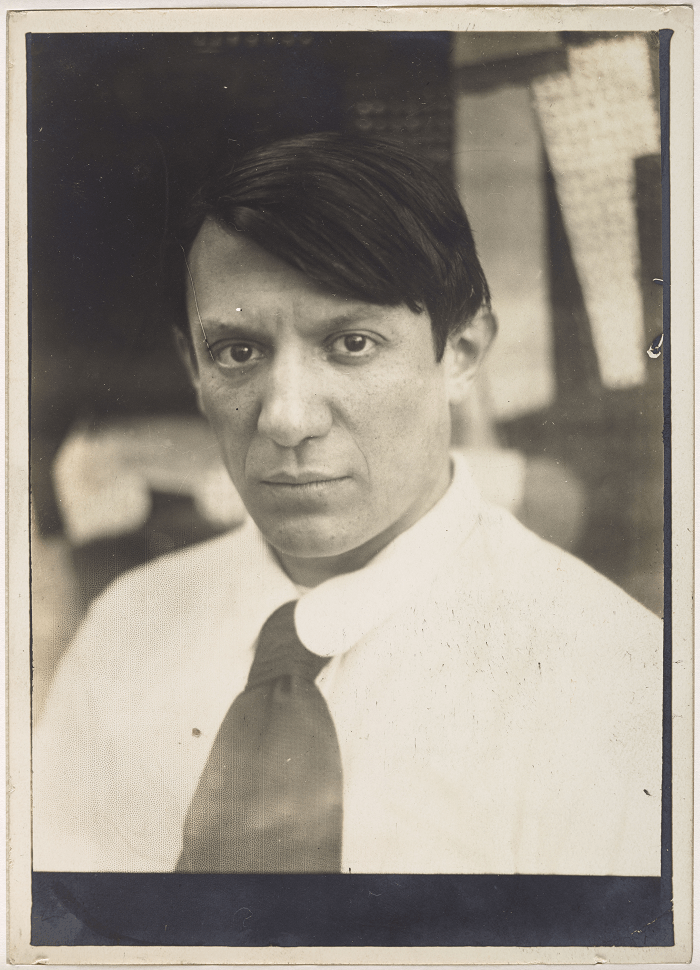

Zayas Georges de (1898-1967) (attribué à), Portrait de Picasso dans l’atelier de la rue Schoelcher. Paris, vers 1915-1916. Photographie, épreuve gélation-argentique. Paris, Musée national Picasso – Paris. Don succession Picasso, 1992, archives personnelles de Pablo Picasso. © Georges de Zayas. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean. © Succession Picasso 2021.

Introduction by Paul Ben-Itzak

Copyright 2021 Paul Ben-Itzak

Apollinaire original French text copyright 1960 Gallimard

On Sunday November 14, while Belarus was using thousands of migrants as weapons by luring them to the country with tourist visas then pushing them off to the Polish border (and thus European Union frontier), as putative revenge for E.U. sanctions, and the government of Poland (putatively a member of the E.U.) was responding by regarding the migrants as weapons in sending 10,000 soldiers to track them down in the forest shared by the two countries so that it could push them back to Belarus, often with water cannons, blocking media and human rights organizations from witnessing and aiding the migrants (and even blocking the deployment of the Warsaw-based European frontier guard Frontex, which would have insisted on a more humane and open handling of the situation. in conformation with E.U. regulations), at least eight of which migrants had already died from the freezing cold and/or lack of water and food (some local Poles did their best to seek them out and offer nourishment and refuge; at least 11 migrants, mostly from Iraqi Kurdistan, including one 1-year-old, eventually died); at the same time the Climate conference was closing with a lack of concrete mandates (or concrete aid to the countries contributing the least and suffering the most from the Climate emergency), which will only increase the flight of migrants from Climate-ravaged countries, the French Republican party was responding with a debate in which each of the five candidates tried to top each other in effectively stoking fear of migrants (they wouldn’t call it this, but rather responsible immigration policies) — of the Other — thus falling into the hands of the Belarusians. The situation reached its nadir when Poland announced plans to build a border wall which in its 50-meter height dwarfs Donald Trump’s, with the Danish government offering to sell them the barbed wire and the E.U. president saying the idea was worth discussing, prompting French European Parliament deputy and Green presidential candidate Yannick Jadot to sadly observe: “We are now doing the same thing that four years ago we were criticizing Donald Trump for doing.” (Meanwhile, the Transnational Institute recently reported that seven of the world’s richest, most polluting countries are spending twice as much on reinforcing border control as on aiding less wealthy, more vulnerable countries.)

As for the Republican debate, it reached its nadir when one of the candidates warned about the threat posed to the national French character if the alleged (alleged because the real numbers show there is no crisis, quantity-wise at least) flow of migrants isn’t stemmed.

Exactly which French national character was she talking about?

The one in which the most famous French detective of the 20th century, Commissaire Maigret, was invented by a Belgian, Georges Simenon?

The one in which the century’s most emblematic male French singer on an international scale was born in Italy, a certain Yvo Montand? (The only serious pretenders to the title — outside Charles Trenet, who is less known internationally –being Belgian Jacques Brel and a certain Shahnourh Varhinag Aznavourian, a first-generation Frenchman born in Paris to a Turkish-born mother and a Georgian-born father, and who you might know better as Charles Aznavour.)

Perhaps the one in which the most famous French comic book character, Tintin, was also invented by a Belgian, Hergé?

Or maybe she meant the national French character being degraded by the country’s most celebrated cabaret entertainer — also a hero of the French Resistance, who risked her life spying for General de Gaulle — being born in East St. Louis: Josephine Baker, who, grace of President Emmanuel Macron, who gets it, on November 30 enters the Pantheon in Paris, where her neighbors will include Victor Hugo, Marie Curie, and Emile Zola?

En fin, perhaps the would-be French Republican party presidential candidate (currently the president of the Ile de France region which includes Paris and its multi-culti suburbs) was referring, national identity threat-wise, to the most influential painter, voir artist, of the 20th century, a certain Spanish-born Pablo Picasso who, a new book and exhibition highlights (if not reveals) was surveilled by French police from the moment he entered the country, whose naturalization request in 1940 was refused, and who demonstrated in irreproachable love and investment in his adopted country for 70 years. (Initiated by the French police, pilfered by the German Occupants, appropriated by the Russians and finally recuperated in 2001 by the French police in whose archives it now resides, an intense analysis of Picasso’s ‘fiche’ by the internationally renowned scholar and curator Annie-Cohen Solal is at the intellectual marrow of the exhibition. The exhibition was no doubt greatly inspired by the museum’s founding president, Benjamin Stora.)

Full-page ad in the Official Guide to the 1931 “Exposition Coloniale Internationale” in Paris. The Palais de la Porte Dorée which now houses the Musée National de l’Histoire de l’Immigration was constructed for the 1931 Colonial Exposition .

Rather than comment further on the art of that artist ourselves, we’ve chosen to illustrate the following images from that exhibition, Picasso: l’Etranger, which runs through February 13 at the Musée National de l’Histoire de l’Immigration (the only such institution in Europe, the museum is housed, fittingly, in the Palais de la Porte Dorée, constructed for the 1931 Colonial Exposition), with the reception he inspired by another foreign-born exponent of the French national character, a certain Guillaume Apollinaire, born in Rome and the most influential French poet of the 20th century (nationalized after volunteering for World War I at the age of 34, a head wound in which contributed to his death in 1918 from the Spanish flu, at the age of 38). Because, and contrary to what the French Republican party presidential postulates would have you believe, France, and its storied capitol, has always been a magnet to ‘etrangers’ like Apollinaire and Picasso, its culture enriched by their presence and its national character broadened not restricted, and it is in no small part this cross-fertilization of international genius with French accommodation of international genius which has helped French culture to shine internationally for more than a hundred years.

Published on May 15, 1905 in Le Plume and only the second piece the poet and burgeoning critic wrote on Picasso, the following piece is collected in “Chroniques d’Art,” published by and copyright Gallimard in 1960, collected and annotated by L.-C. Breunig. And translated by PB-I. — PB-I

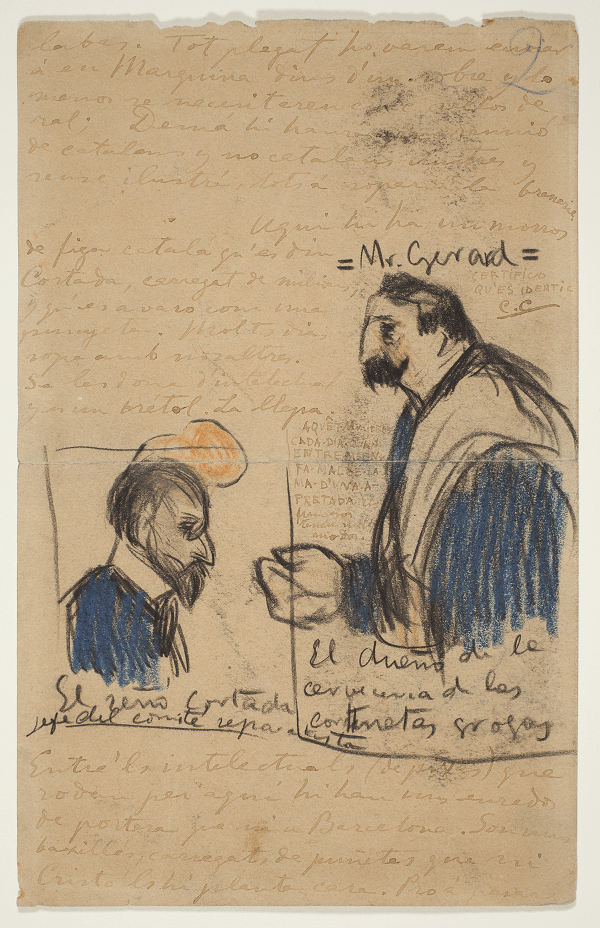

Pablo Picasso et Carlos Casagemas, Lettres aux Reventos. 25 octobre 1900 Dr Jacint Reventos i Conti Collection / ou Fondacio Picasso-Reventos (Barcelone). En dépôt au Musée Picasso Barcelone. © Succession Picasso 2021.

The young generation: Picasso, Painter

Text by Guillaume Apollinaire & Copyright Gallimard

Translated by Paul Ben-Itzak

Images from the exhibition Picasso l’Etranger (see captions for copyrights)

For those who know, all the gods come to life.

Born of the profound understanding that Humanity retains of itself, the coddled pantheisms which resemble this humanity have become more supple. But despite the eternal slumbering, there are eyes in which are reflected humanities similar to divine and joyous ghosts.

These eyes are attentive like flowers which always want to contemplate the Sun. Oh fecund joy! There are men who see with these eyes.

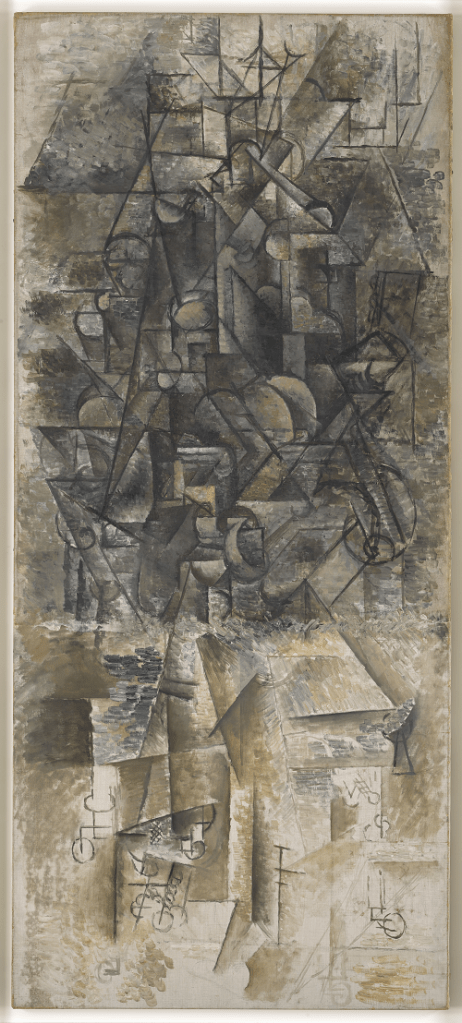

Pablo Picasso, Un Homme à la mandoline. Automne 1911. Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean. © Succession Picasso 2021.

Picasso has contemplated the human images floating in the azure of our memories and which partake of the divinity to produce metaphysicians. How pious they are, these heavens awhirl in flight, these lights heavy and low like those of caves!

There are the children who roam about without learning the catechism. They stop moving and the rain stops with them: “Regard! There are people who live before these buildings and their garments are poor.” These children who no one embraces understand so much. Mama, love me dearly! They know how to leap and the turns they execute are like mental evolutions.

Pablo Picasso, La Lecture de la Lettre, 1921. Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau © Succession Picasso 2021.

These woman no longer loved remember. They’ve dwelled too much on their brittle thoughts. They don’t pray; they are devoted to memories. They huddle in the twilight like an old church. These women have given up and their fingers twist braiding crowns of straw. With the day they disappear, finding consolation in the silence. They’ve passed through many doorways: the mothers guard the cradles so that the new-born don’t fall prey to maledictions; when they lean over them the little children smile in the knowledge that they are so good.

They are often thanked and the gestures of their forearms tremble like their eyelids.

Pablo Picasso, Tête de femme, 1929-1930. Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau © Succession Picasso 2021.

Enveloped in bracing fog, the old people wait without meditating, because only the children meditate. Animated by distant lands, by the squabbles of animals, by fatigued hair, these old people can beg without shame.

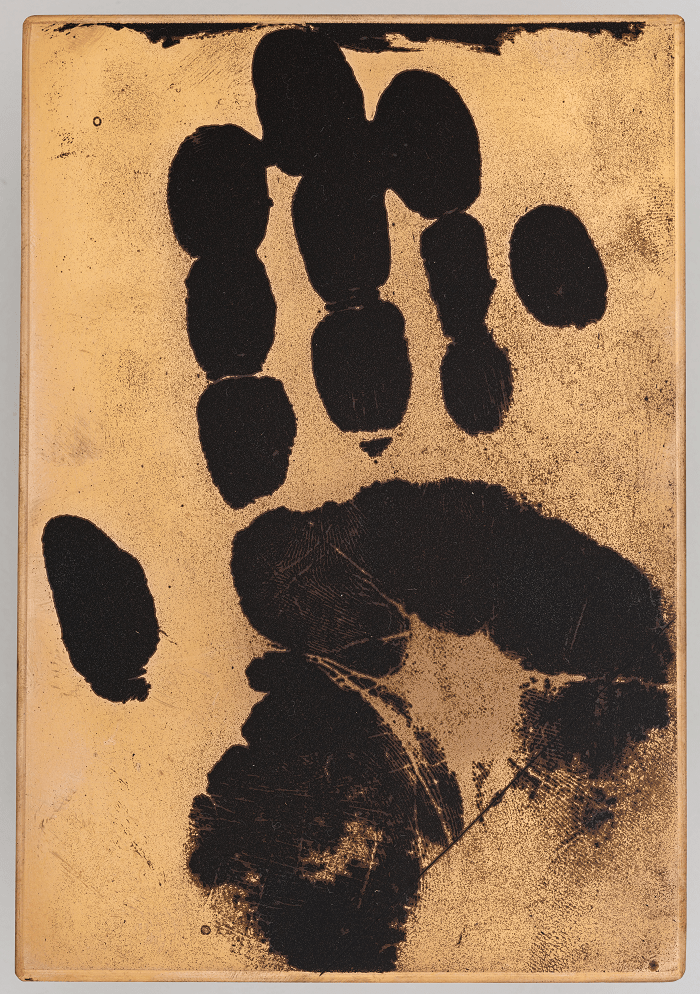

Pablo Picasso, Empreinte (au sucre) de la main de Picasso. Début juin 1936. Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris)/ Mathieu Rabeau © Succession Picasso 2021.

Then there are the mendicants worn out by life. These are the crippled, the hobbled, the scoundrels. They’re surprised to have reached the goal-line which is still blue but is no longer horizon. Ageing, they’ve turned into madman, like kings who have too many troops of elephants bearing tiny citadels. There are travelers who confound the flowers with the stars.

Récépissé de demande de carte d’identité datant de 1935. © Archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris. © Succession Picasso 2021.

Prematurely aged like cows who die at 25, they take the breastfed babies to the moon.

In a new day, women stop talking, their bodies are angelic and their regards trembling.

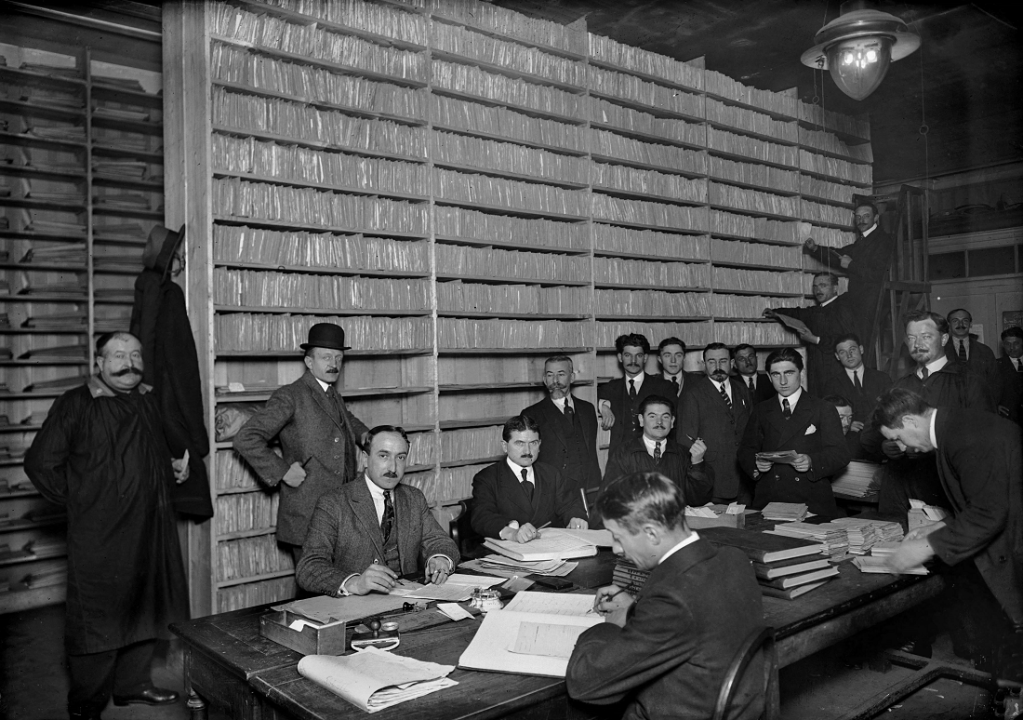

Anonyme. Service des étrangers de la préfecture de Police de Paris. Années 1930 © Archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris. © Succession Picasso 2021.

Conscious of danger, their smiles are internalized. They await the terror to confess to innocent sins.

In just a year, Picasso has lived this moist painting, blue like the humid depths of the abyss and pitiful.

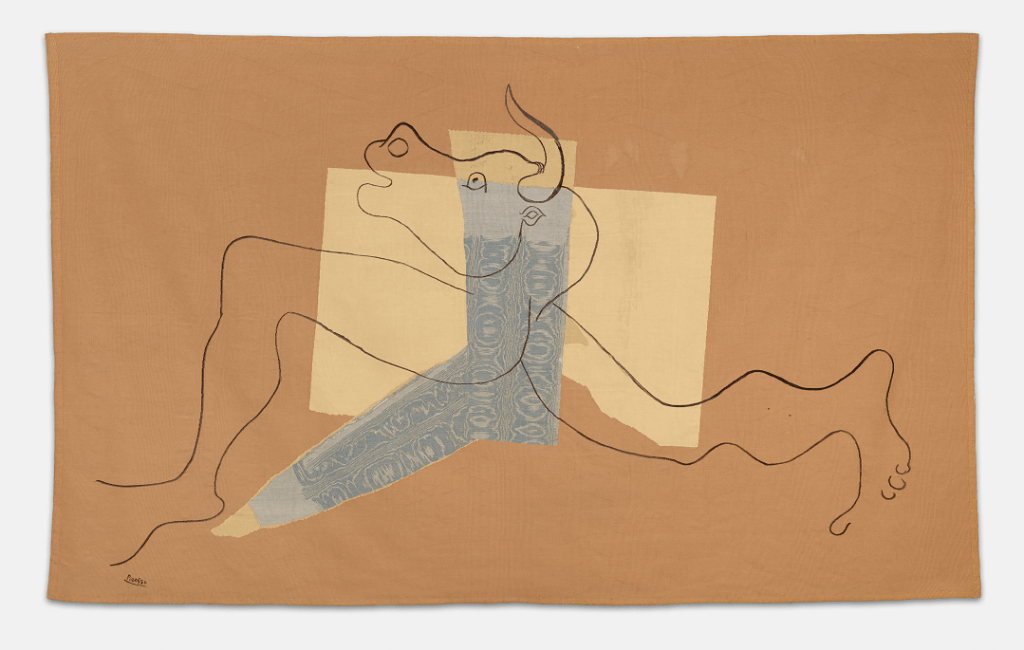

Pablo Picasso et Marie Cuttoli, Le Minotaure (tapisserie), 1935. Musée Picasso, Antibes. © Succession Picasso 2021.

The pity made Picasso harsher. The town squares with a hanged man stretched out against the houses above oblique passersby. These torture victims await a redeemer. The cord hanging over, miraculous; in the attics the panes are inflamed with flowers in the windows.

In their rooms, artist-painters sketch golden nudes under kerosene lamps. The abandoned woman’s boots at the foot of the bed signify a tender haste.

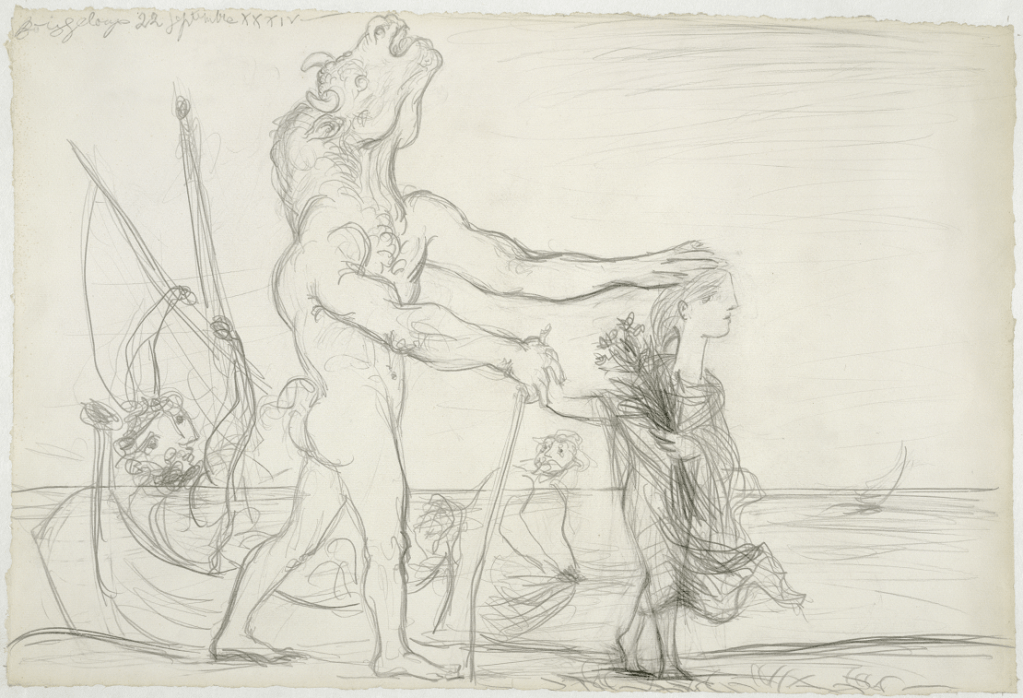

Picasso Pablo, Minotaure aveugle devant la mer, conduit par une petite fille, (1881-1973). Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Béatrice Hatala. © Succession Picasso 2021.

Calm follows this frenzy.

The harlequins live under rags when the painter gathers, heats, or lightens his pigments to express the force and the duration of passions, when the lines limited by the tank-top curve, cut, or shoot out.

Paternity transfigures the harlequin in a square room, while his wife douses herself in cold water and admires herself, svelte and as lanky as her puppet-husband. A neighboring household warms its covered wagon. Beautiful songs are interlaced, and the soldiers move on, cursing the day.

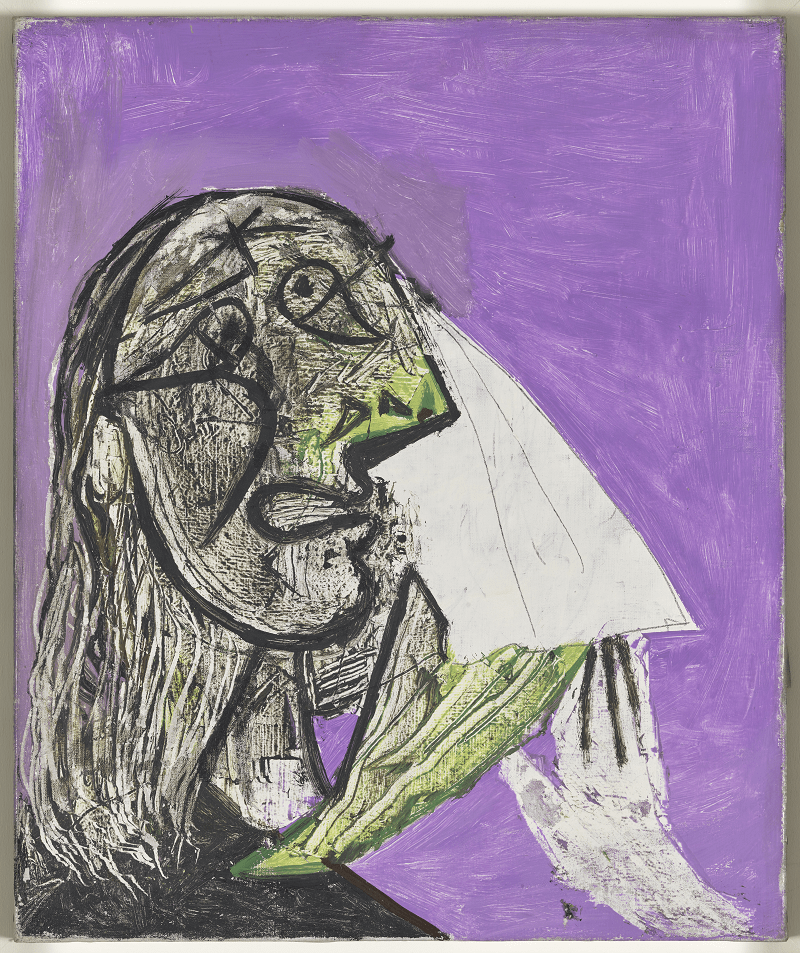

Pablo Picasso, Femme qui pleure, 18 octobre 1937. Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean. © Succession Picasso 2021.

Love is good when one adorns it and the habit of living in one’s own home is doubled by paternal sentiment. The child gets closer to the father of the woman, who Picasso wants to be glorious and immaculate.

The mothers, primping and preening, no longer await the child, perhaps because of certain chattering crows who bode ill tidings. Christmas! They give birth to future acrobats among familiar apes, white horses, and dogs like bears.

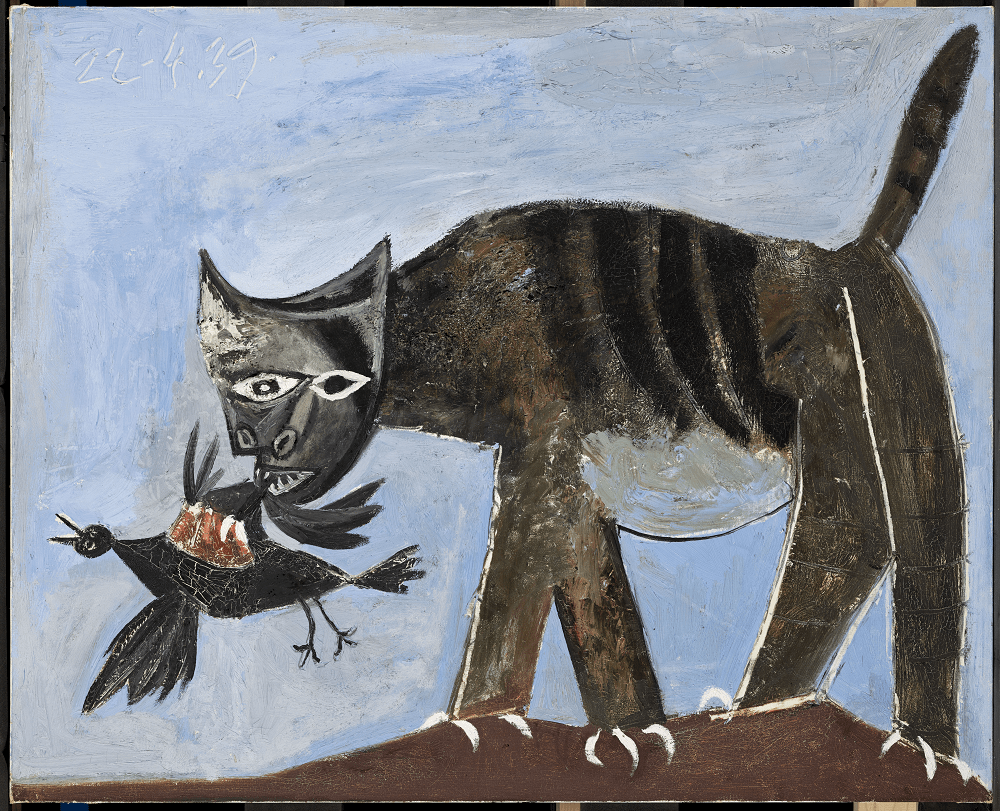

Pablo Picasso, Chat saisissant un oiseau, 22 avril 1939. Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau. © Succession Picasso 2021.

The teenage sisters, balancing in equilibrium on the large balls of saltimbanques, command over these spheres the radiant movement of worlds. These pre-pubescent adolescents harbor the worries of innocence, the animals teach them the religious mystery. Harlequins accompanying the glory of the women, they resemble them, neither male nor female.

The color has the flatness of fresques, the lines are firm. But placed at the limit of life, the animals are human and the penises imprecise.

Hybrid beasts have the conscience of Egyptian demi-gods; taciturn harlequins sport cheeks and foreheads withered by morbid sensitivities.

Pablo Picasso, Coq tricolore à la croix de Lorraine, 1945. Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / image RMN-GP © Succession Picasso 2021.

One cannot confuse saltimbanques with hammy actors. Their spectators must be pious, because they celebrate silent rites with a difficult agility. This is what distinguishes this painter from the Greek potters which his drawing at times resembles. On their painted earthenware, bearded and loquacious priests offer up in sacrifice resigned animals sans destiny. Here, the virility is beardless, but manifests itself in the nerves of emaciated arms, the planes of visages, and the animals are mysterious.

Picasso’s taste for a line which flees change and penetrates and produces practically unique examples of linear dry points in which the general aspects of the world are barely altered by the lights which modify the forms by changing the colors.

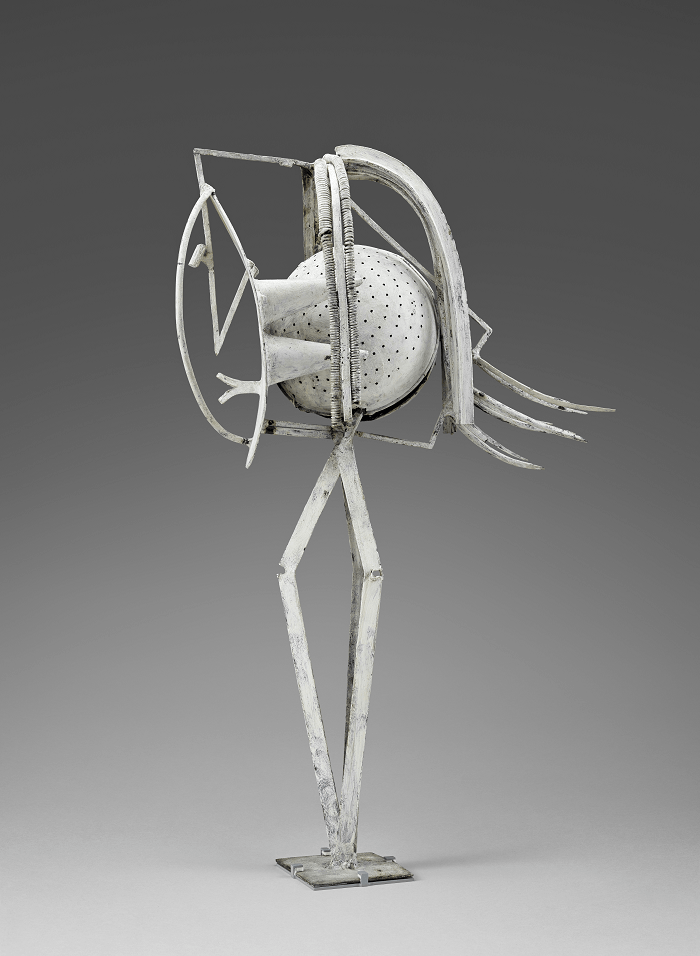

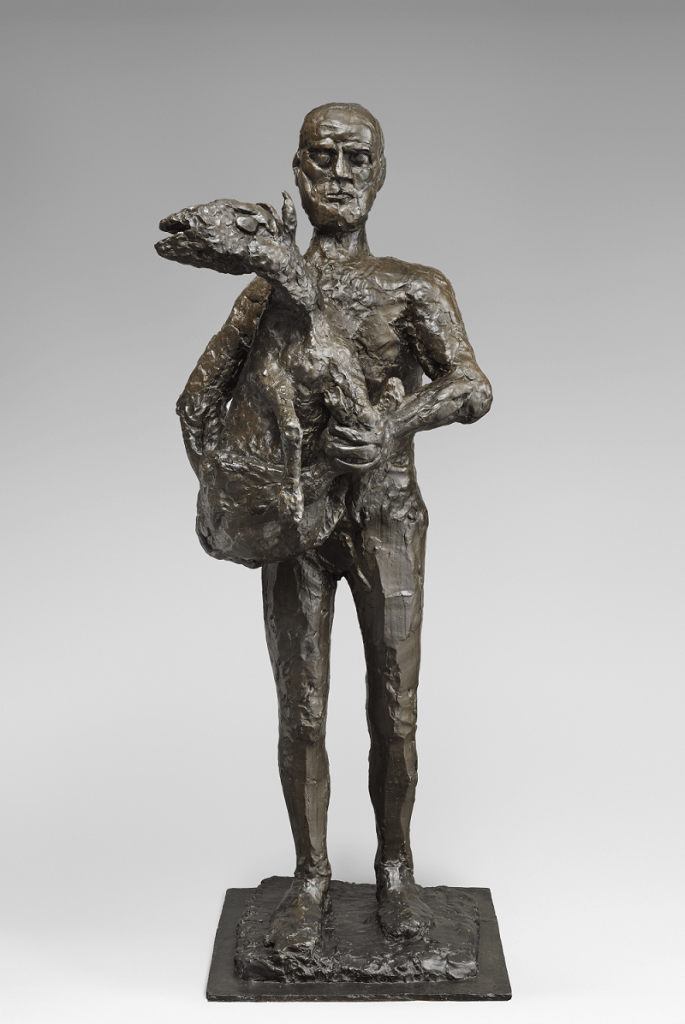

Pablo Picasso, L’Homme au mouton (don à la ville de Vallauris), 1943. Paris, musée national Picasso – Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean. © Succession Picasso 2021.

More than all the poets, the sculptors, and the other painters, this Spaniard jolts us like a sudden frost. He comes to us from faraway, the compositional richness and brutal decoration of the Spaniards of the 17th century.

Those who have known him will remember the rapid vividness which was already surpassed test-runs.

His insistence in the pursuit of beauty steered him towards his paths. He sees himself as more Latin morally, more Arab rhythmically.

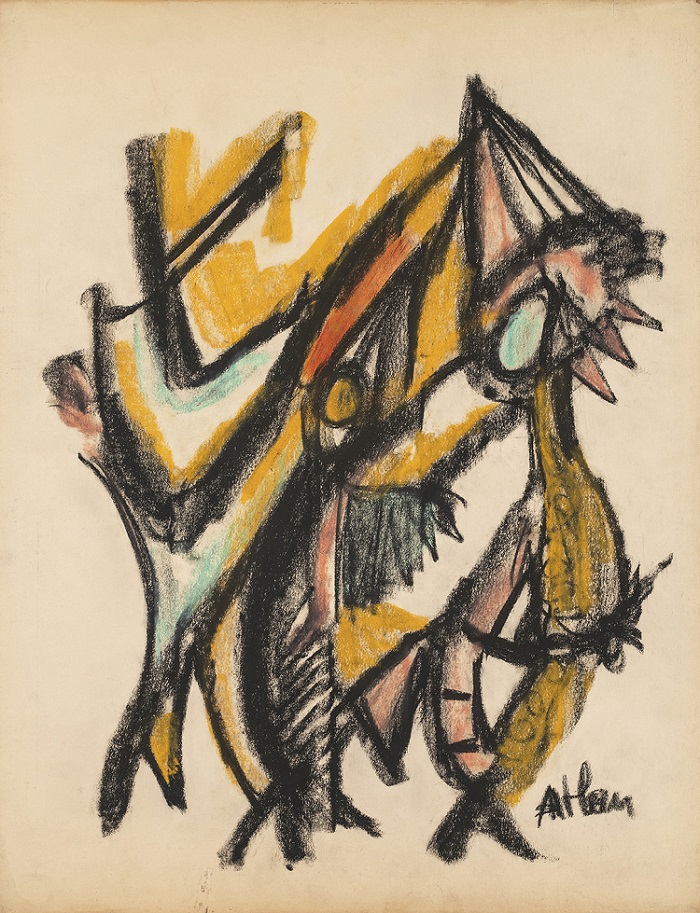

Often lost among the quarrel between the Abstracts and the Figuratives of the 1950s (and the critical partisans of their schools) was the achievement of work which — sometimes depending on the eye of the viewer — traversed both terrains. Thus it is no surprise that for an exhibition which by its name alone, Animal Totem, promises a degree of concreteness, the Galerie

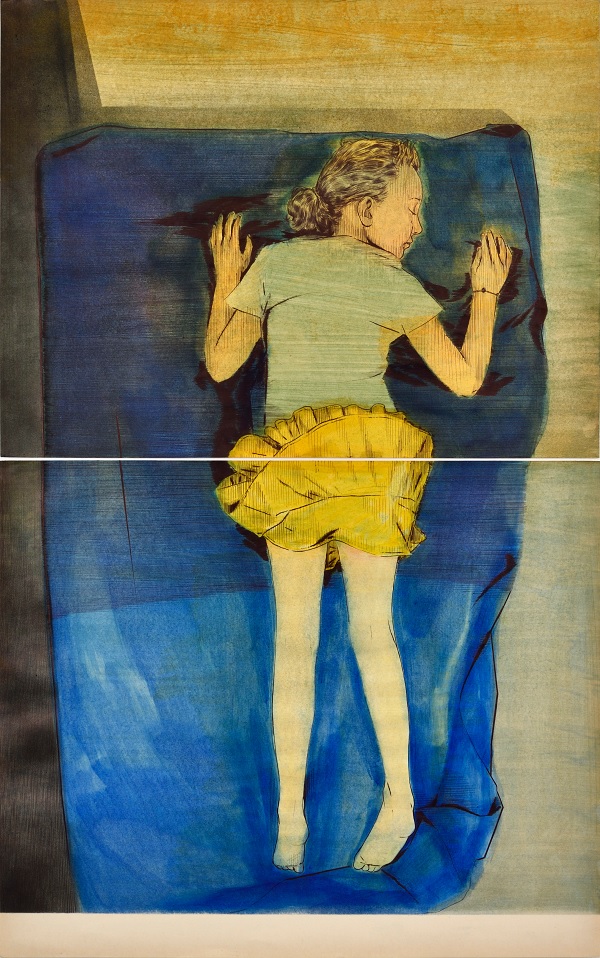

Often lost among the quarrel between the Abstracts and the Figuratives of the 1950s (and the critical partisans of their schools) was the achievement of work which — sometimes depending on the eye of the viewer — traversed both terrains. Thus it is no surprise that for an exhibition which by its name alone, Animal Totem, promises a degree of concreteness, the Galerie  When an Anarchist meets the Avant-Garde in Paris et NY: From the exhibition Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde — From Signac to Matisse and Beyond, running October 16 through January 27 at the Orangerie in Paris (in a slightly neutered title: Les temps nouveaux, de Seurat à Matisse) and March 22 through July 25, 2020 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York: Henri Matisse, “Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading),” Paris 1905–06. Oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 23 1/2″ (72.7 x 59.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller, 1991. Photo by Paige Knight. © 2019 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

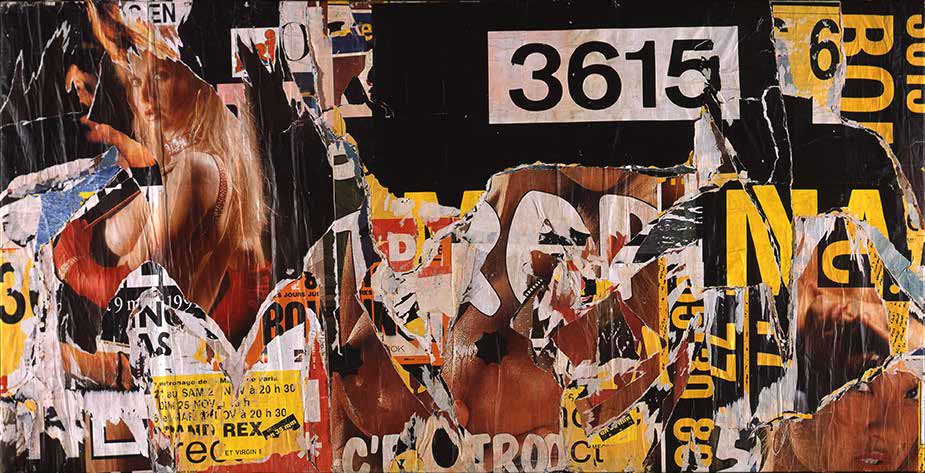

When an Anarchist meets the Avant-Garde in Paris et NY: From the exhibition Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde — From Signac to Matisse and Beyond, running October 16 through January 27 at the Orangerie in Paris (in a slightly neutered title: Les temps nouveaux, de Seurat à Matisse) and March 22 through July 25, 2020 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York: Henri Matisse, “Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading),” Paris 1905–06. Oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 23 1/2″ (72.7 x 59.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller, 1991. Photo by Paige Knight. © 2019 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.  It’s fitting that Jacques Villeglé — like the pioneer in the art of the lacerated street poster (and the modern French detective novel) Léo Malet in the 1930s, an inveterate street-walker — realized his final work in removing and re-constituting the posters for erotic “message boxes” on the Mintel (the French ancestor of the Internet) that began plastering the rues of Paris between 1989 and 1992, when posters became largely supplanted by billboards. “There’s a certain affinity between the artist and these modern Lorettes,” Harry Bellet writes for the catalog of the works’ exhibition, running through April 12 at the gallery Vallois in Paris. “Like (the subjects of the posters), he walked the streets…. He also has an admirable respect for them: They display themselves — or rather they’re plastered up. He unglues them, liberates them…. Sometimes he tears them up, certainly, but as he confided to Nicolas Bourriaud…, ‘A wounded visage is still beautiful.’ In fact, Villeglé hasn’t lacerated these women; he’s softly, tenderly, langorously but always lovingly blown the leaves away.” Above: Jacques Villeglé, “Route de Vaugirard, Bas-Meudon, April 1991,” 1991. Lacerated poster mounted on canvas, 152 x 300 cm. Copyright Jacques Villeglé and courtesy Galerie Vallois.

It’s fitting that Jacques Villeglé — like the pioneer in the art of the lacerated street poster (and the modern French detective novel) Léo Malet in the 1930s, an inveterate street-walker — realized his final work in removing and re-constituting the posters for erotic “message boxes” on the Mintel (the French ancestor of the Internet) that began plastering the rues of Paris between 1989 and 1992, when posters became largely supplanted by billboards. “There’s a certain affinity between the artist and these modern Lorettes,” Harry Bellet writes for the catalog of the works’ exhibition, running through April 12 at the gallery Vallois in Paris. “Like (the subjects of the posters), he walked the streets…. He also has an admirable respect for them: They display themselves — or rather they’re plastered up. He unglues them, liberates them…. Sometimes he tears them up, certainly, but as he confided to Nicolas Bourriaud…, ‘A wounded visage is still beautiful.’ In fact, Villeglé hasn’t lacerated these women; he’s softly, tenderly, langorously but always lovingly blown the leaves away.” Above: Jacques Villeglé, “Route de Vaugirard, Bas-Meudon, April 1991,” 1991. Lacerated poster mounted on canvas, 152 x 300 cm. Copyright Jacques Villeglé and courtesy Galerie Vallois. For Flowers for Valentine’s, running through March 16 at the Galerie Catherine Putnam at 40, rue Quincampoix in Paris, Frédéric Poincelet has curated a group show including work by Marc Desgrandchamps, Blutch, Ugo Bienvenu, and, above, David Hockney, “Sunflower I” (347), 1995. Engraving, 80 ex./ Arches 69 x 57 cm. Copyright David Hockneystudio. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

For Flowers for Valentine’s, running through March 16 at the Galerie Catherine Putnam at 40, rue Quincampoix in Paris, Frédéric Poincelet has curated a group show including work by Marc Desgrandchamps, Blutch, Ugo Bienvenu, and, above, David Hockney, “Sunflower I” (347), 1995. Engraving, 80 ex./ Arches 69 x 57 cm. Copyright David Hockneystudio. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.  From the Arts Voyager archives: Paul Klee, Untitled, 1939. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

From the Arts Voyager archives: Paul Klee, Untitled, 1939. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.