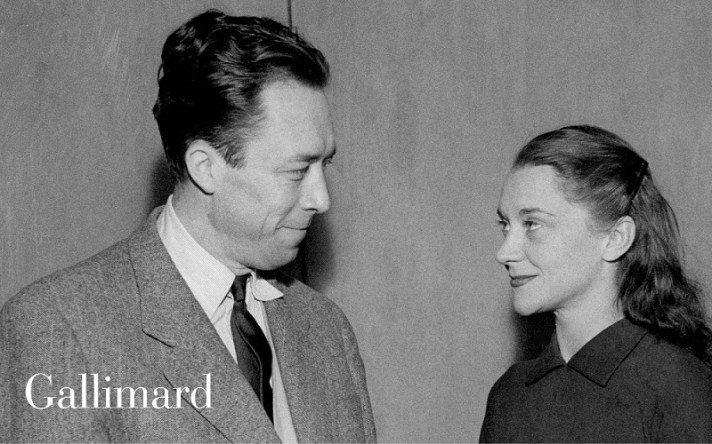

Albert Camus and Maria Casarès. Book cover photo courtesy Gallimard.

Albert Camus and Maria Casarès. Book cover photo courtesy Gallimard.

by Paul Ben-Itzak

Commentary copyright 2018 Paul Ben-Itzak

(Like what you’re reading? Please let us know by making a donation so that we can continue this work. Please designate your PayPal donation to paulbenitzak@gmail.com , or write us at that address to learn how to donate by check.)

Previously explored by Olivier Todd in his exhaustive 1996 Gallimard biography and insinuated in Simone de Beauvoir’s memoirs, Albert Camus’s inherent self-doubt — in all areas of his life – as he struggled to live up to the principles he extolled for others is now decisively confirmed by the novelist-journalist-philosopher-playwright’s 16 years and 1,275 pages of correspondence with his longtime mistress (for want of a word which would do better justice to their fidelity) Maria Casarès, recently published for the first time by Gallimard after being released by Camus’s daughter Catherine, who inherited the letters from the actress. Portions of the correspondence will be recited this month at the Avignon Festival by Lambert Wilson, whose father George worked with Casarés (including at Avignon), and Isabel Adjani.

A die-hard Camusian ever since being assigned to read “The Plague” in high school (thank you, Ralph Saske), of course I had to request a review copy from the publisher as soon as the correspondence came out, putatively for this article, but with the ulterior ambition of being the first to translate the letters into English and trying to find an American publisher.

Because of the period covered (the pair became lovers in Paris on D-Day 1944, split up the following fall when Camus’s wife Francine returned from Algeria, and reunited in 1948 after bumping into each other on the boulevard Saint-Germain-des-Pres, remaining together until Camus’s death in a traffic accident on January 4, 1960), I’d hoped to find new insight into Camus’s thought process in preparing “The Fall,” “The Rebel,” and the unfinished autobiographical novel “The First Man” — the hand-written manuscript of the first 261 pages were found among the wreckage and later published by Gallimard — as well as his inner reasoning as he struggled to come up with a resolution for the conflict and war in Algeria, where Camus’s efforts to square his principles with the well-being of his family in the French colony, his birthplace, tore him apart, and his public views pissed off everyone on both sides. (The author ultimately proposed an autonomous state federated with France, and where the ‘colonists’ would be allowed to remain.) From Casarès — the busiest stage and radio actress of the fertile post-War Parisian scene, a major film presence (she played Death in Jean Cocteau’s 1949 “Orpheus”), and the daughter of a former Republican president of Spain — I’d relished the potential accounts and impressions of the playwrights and directors she worked with, a real’s who-who of the French theater world during the Post-War epoch (as attested to by Béatrice Vaillant’s thoroughly documented footnotes), notably Jean Vilar, founder of the Theatre National Populaire and the Avignon Festival.

Unfortunately (if understandably; this is not a criticism of the correspondents, but of Gallimard’s ill-considered decision to make their private, often banal dialogue public), in fulfillment of their main purpose of maintaining the link during their often long separations, necessitated by his retreats for writing, author tours, visits to his family in Algeria, tuberculosis cures, and family vacations — he never divorced Francine — and on hers by performance tours, apart from the travelogues (except where they describe her vacations by the Brittany and Gironde seaside, more interesting on his part), their letters are often dominated by declarations of love and the sufferance of absence (even if your name is Albert Camus, there are only so many interesting ways to say I love you, I want you, I need you), and the often anodyne details of their daily lives apart. Camus tells her to leave nothing out, understandable for an often absent lover, but which ultimately reveals her frivolity and recurrent prejudices (particularly when it comes to male homosexuals, who according to Casarès are typically vengeful). Her manner of chronicling her quotidian activities is often so indiscriminate, investing theatrical rendez-vous with the same level of importance as shopping excursions for furniture to decorate her fifth-floor flat with balcony on the rue Vaugirard, that at one point he mildly rebukes her, “Don’t just write that you had a luncheon appointment, say who it was with.” The best she can come up with to describe the experience of making “Orpheus” with Cocteau is that she was annoyed by the autograph-seekers who showed up at the outdoor shoots, not the only instance where she disdains her public. And when it comes to the radio productions which seem to constitute her main employ, at least in Paris, she often refers to “having a radio today,” without even naming the play in question. (When Camus refers to “a radio,” he means an x-ray to analyze the progress or regression of the chronic tuberculosis which dogged him all his life.) Never mind that the radios in question were plays by the leading European writers of the day, as well as classics. But the part I found myself resenting a bit – as someone who would have loved to have had a tenth of the dramatic opportunities Casarès did – is that at times she seems to treat her theater work, particularly the radio recordings, as almost onerous. (This morning on French public radio, in a live interview from the same Avignon festival, the director Irene Brook, Peter’s daughter, recognized that “we’re very privileged to be able to pass our days rehearsing theater.”)

When it comes to discussing his work, at most Camus refers to his progress on the literary task at hand or writers’ blocks impeding it, rarely going into the philosophical or political issues he’s grappling with – some of the headiest of the Post-War period, French intellectuals’ inclination towards which Camus was instrumental in forming. As for the letters from Algeria, typically occasioned by visits to his mother, uncle, and brother’s family, if Camus’s native’s appreciation for and adoration of the landscape is apparent, even lyrical (particularly in recounting excursions to Tipassa), he dwells mostly on his ageing mother’s maladies, and rarely comments on the sometimes violently contested political encounters he was having at the time. If anything, their relationship was their havre, a refuge and sanctuary from the demands of his calling and the rigors of what she seems to have considered more obligations than labors of love. (From his letters to his wife cited by Todd – at one point he tells her he regards her more as a sister than a spouse – Camus was much more likely to discuss his thinking process with Francine than with Casarès, at least in his letters.)

This is not to say there are no newsworthy stories here. For Camus, the story, albeit one already explored by Todd in his biography (for which Todd apparently had access to the letters), is the author-philosopher’s continually frustrated efforts to live his private life in accordance with his public principles. Moral responsibility (and fidelity) to one’s community, and the need to be exemplary even in the most trying of circumstances and times — two of the principal themes of “The Plague” — dictate that he remain in a conjugally loveless marriage, which means he can never shack up for good with the woman he loves, to her great frustration. (Never mind that he’s an atheist — which he hedges here at times by asking Casarès to pray to her god, sometimes on his behalf — Francine is a practicing Catholic.) The right, voir obligation, to be happy — another pillar central not only to “The Plague” but Camus’s over-riding philosophy of positive Existentialism, where one must still find meaning even in the most trying of circumstances — would insist that he fully commit himself to Casarès and the complete realization of their love. Because he ultimately can’t square the two principles, everyone — Francine, Maria, and himself — is often miserable.

A fourth, and perhaps the author’s most personally invested, theme of “The Plague” — absence and separation — is indeed one of the two principal unifying themes that emerge from the letters, but given that the book was published in 1948, when their relationship began in earnest, at best the letters furnish an after-the-fact illustration and elaboration of this theme, their particular separations having played no role in its actual development. (The absence and separation which inspired “The Plague” being the one the war imposed between the author and his wife Francine, who remained in Algeria.)

If there is a bonafide, universally resonant story here (besides the humanizing of a super-human philosopher), it is that of the ultimate unconditional love. After some initial resistance (expressed in face to face, and animated, arguments referred to and regurgitated in her letters), Casarès never demands that Camus leave his wife, even though it means she can’t have a true domicile conjugal, with a companion and children to come home to (at least as manifest in the letters, she remained loyal to him, even though he had at least two other mistresses during the time they were together, according to Todd). For his part, if he doesn’t hear from her for more than a week when they’re apart, he worries that she might be drifting away and sinks into a morose depression, unable even to work. If I know these things — here’s where the unconditionality comes in — it’s because they’ve made a pact, referred to in the letters, to share everything without holding back, no matter how ridiculous or petty the sentiment might seem. And they stick to this agreement faithfully.

The other element that links the author and the actress — how they fulfill and complete each other — is a shared, desperate need for nature, primarily the sea (although he’s also able to appreciate the pictorial value of the mountainous terrains he often finds himself confined to, for writing and health retreats; but we didn’t need the publication of these letters to know that Camus was an adroit paysagist). Maria’s most brilliant and moving passages describe her merging with the sea on an island in Bretagne or off a beach in the Gironde, her two vacation retreats. (If I use the first name, it’s because on these occasions, watching her galloping into the waves to meet the surf head on, I feel like I’m discovering the child inside the woman.) Camus’s descriptions of a return to Rome — which he values as a living monument to art and archeology — are also inspiring (they made me want to go there, or at least watch “Roman Holiday” again), and a personal review of a London production of “Caligula” that he finds lacking is scathingly funny.

The most poignant moment comes not so much at the juncture we expect — Camus’s final letter, of December 30, 1959, alerting Casarès he’ll arrive back in Paris by the following Tuesday “in principal, barring hazards encountered en route,” and where he looks forward to embracing her and “recommencing” — but earlier in the same year. Casarès has just decided to leave the TNP (over Vilar’s latest caprices, this time insisting on his right to call the actors during a well-earned vacation), after five years, which followed a shorter stay at the stodgy Comedie Française. I dream of living in a roulotte — or covered gypsy wagon — and hitting the road, she tells him. (He’s welcome to join her, but her plans don’t depend on that eventuality.) He encourages this dream, but notes, in the manner of a supportive but prudent parent, that she should realize that just because she’ll be living in a roulotte doesn’t mean she’ll be free and independent; it just means she’ll be living in a community surrounded by other roulottes. “Even in roulottes, there are rules.” This could be an analogy for their 16-year relationship, an emotional vagabondage inevitably — and fatally — tethered by the rigors, responsibilities, and rules of living in good society.

If the example of unconditional love revealed in the letters is compelling and inspiring, the moral problem I have with Gallimard’s publishing them is that there’s no indication that the professional writer involved intended for them to be made public. The problem is not just one of intrusion and indiscretion (Todd cites a note to Camus from Roger Martin du Garde to the effect that a writer owes the public his work, not his private life, inferring from this that Camus subscribed to the same belief), but that *with works he knew were destined for publication*, Camus was a scrupulous and meticulous perfectionist. Counting the war, “The Plague” took eight years to write, from gestation to publication. “The First Man” started germinating in 1952, and by the author’s death eight years later was only one third finished, according to his outline. Both Todd’s biography and the letters themselves confirm that Camus worked, re-worked, and re-wrote his books and articles, and even after they were published continued to be besieged by doubts. (Notably over “The Rebel,” virulently attacked by Sartre and his Modern Times lackey Francis Jeansen, the former not confining himself to taking on the treatise’s arguments but attacking Camus personally, like a Sorbonne senior with a superiority complex upbraiding an underclassman who has the moxey to challenge him.)

If an argument can be made for making them available to researchers for biographical purposes — in the archives of the Bibliotheque Nationale, for example, or of the university in Aix-en-Provence, a region where many of Camus’s papers are located — my feeling, as a Camus loyalist, is that these letters should not have been published. If Catherine Camus’s motivations in releasing them should not be questioned — she’s been an assiduous guardian of her father’s legacy, and who can interject themselves into the complex considerations, even after death, created by the relationship between a daughter and the father she lost prematurely at age 14? – I’m flummoxed by Gallimard’s decision, given the meager literary and biographical value of the result. (A caveat and reservation: Camus does tell Casarès at one point that everything in him which connects him to humanity, he owes to her; at another, on July 21, 1958: “As the years have gone buy, I’ve lost my roots, in lieu of creating them, except for one, you, my living source, the only thing which today attaches me to the real world.”)

After finishing them, I was still, nonetheless, on the bubble about the letters’ inherent worth, and worthiness as a translation project. What red-blooded Camusian doesn’t want to be the first to translate freshly released words by his idol into English?! Less self-interestedly, I considered that perhaps the lessons of this extraordinarily unconditional love justified the value to potential English-language readers of a translation. And then there was the lingering vision of Maria running joyously, fearlessly into the waves in the Gironde, or holed up in a cave on the obscure side of a Brittany island as the tide rises and the waves begin to crash against the uneven rocks under her naked feet, imperiling her own life and engendering Camus’s chagrin when she describes the episode to him. And above all the penultimate image of Casarès, liberated by a relationship whose restrictions might have fettered anybody else, terminating her contract with the TNP and setting off to see the world in a roulotte, after Camus’s parting advice to be careful. When it informed me that the book was still in the “reading” stage at several Anglophone publishers, with no firm commitment for a translated edition, I even asked the foreign rights department at Gallimard if it would be open to a partial, selective translation of the letters.

But then, after dawdling over the 1,275 pages of correspondence between Maria Casarès and Albert Camus for three months, I read Gallmeister’s 2014 translation of Kurt Vonnegut’s “Breakfast of Champions” and was reminded of what literature is. (This despite the rudimentary translation; it reads like one.) And isn’t. Albert Camus, like Kurt Vonnegut, set a high bar for what constituted literature, working it, re-working it, and re-working it again before he felt it was ready for his public. (And even then, continued to be wracked by doubts.) These letters were not meant for that public. When Vonnegut, for “Breakfast of Champions,” decided to share his penis size, he knew he was exposing himself on the public Commons. When Camus shared his innermost thoughts, doubts, and fears with the most important person in his life, he did not.

Post-Script: Because you got this far and deserve a reward; because they do reveal a rare lighter side to Camus which, their correspondence suggests, Casarès was at times able to elicit from an author whose work rarely reveals a sense of humor; because I can’t resist the urge to translate, for the first time in English, at least a smidgeon of previously unreleased Camus; and above all because these morsels were at least theoretically intended for a public larger than their couple, voila my renderings of several “search apartment with view on ocean” letters written by Camus on Casarès’s behalf in 1951 and 1952 appended to the correspondence (and which serendipitously mirror my own current search):

Dear Sir,

At times I dream — living in the midst of flames as I do, because the dramatic art is a pyre to which the actor lights the match himself, only to be consumed every night, and you can imagine what it’s like in a Paris already burning up in the midst of July, when the soul itself is covered in ashes and half-burned logs, until the moment when the winds of poetry surge forth and whip up the high clear flame which possesses us — at times I dream, therefore, and as I was saying, and in this case the dream becomes the father of action, taking on an avid and irreal air, I dream, at the end of the day, of a place sans rules or limits and where the fire which pushes me on finally smolders out, I’ve been thinking that your coast with its nice clear name would not refuse to welcome the humble priestess of [Th… ], and her brother in art, to envelope their solitude in the tireless spraying of the eternal sea. Two rooms and two hearts, some planks, the sea whistling at our feet, and the best possible bargain, this is what I’m looking for. Can you answer my prayers?

Maria Casarès

Dear Madame,

Two words. I’m hot and I’m dirty, but I’m not alone. The beach, therefore, and water, two rooms, wood for free or next to nothing. Looking forward to hearing back from you.

Maria Casarès

PS: I forgot: August.

Dear Sir or Madame,

Voila first of all what I want forgive me I’m forced to request this from you but everything’s happening so fast and everyone’s talking and talking and nothing comes from all the talking it’s too late so here’s what I need I am going in a bit with my comrade to take the train to Bordeaux it gets better it’s on the beach and even better it doesn’t cost anything question that is to say I don’t have any money but I’m confident. So, goodbye, monsieur, and thanks for the response which I hope comes soon it’s starting to get hot here.

Maria Casarès

To a housing cooperative

Two rooms please open on the night

I’ll cluster my people and hide my suffering

As far as money goes it’s a bit tight

I’ll be on the coast but no ker-ching, ker-ching.

— Albert Camus, for Maria Casarès, translated (liberally) by Paul Ben-Itzak

From the Arts Voyager / Paris Tribune archives: From our coverage of the 2018 Museum of Modern Art exhibition Is Fashion Modern?, Display figures with hijab, in East Jerusalem market. Photo by Danny-w. Some rights reserved. Used through Creative Commons. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

From the Arts Voyager / Paris Tribune archives: From our coverage of the 2018 Museum of Modern Art exhibition Is Fashion Modern?, Display figures with hijab, in East Jerusalem market. Photo by Danny-w. Some rights reserved. Used through Creative Commons. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection.

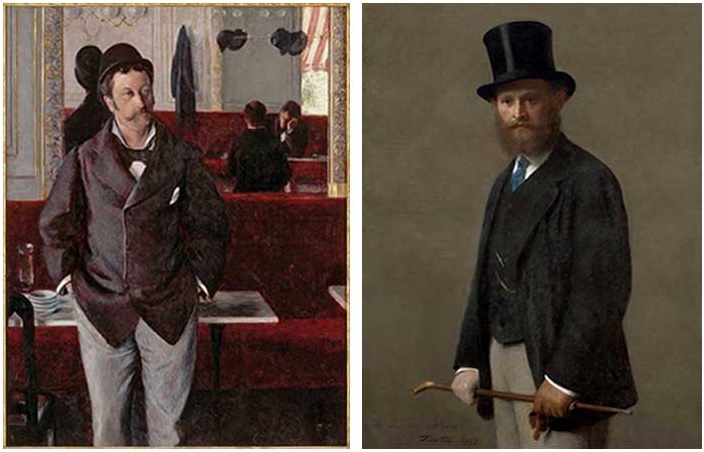

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection. Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.)

Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.) Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart.

Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart. Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry.

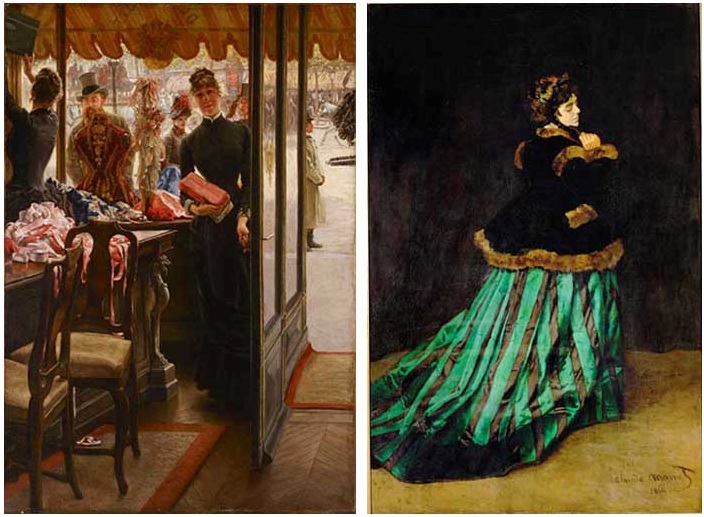

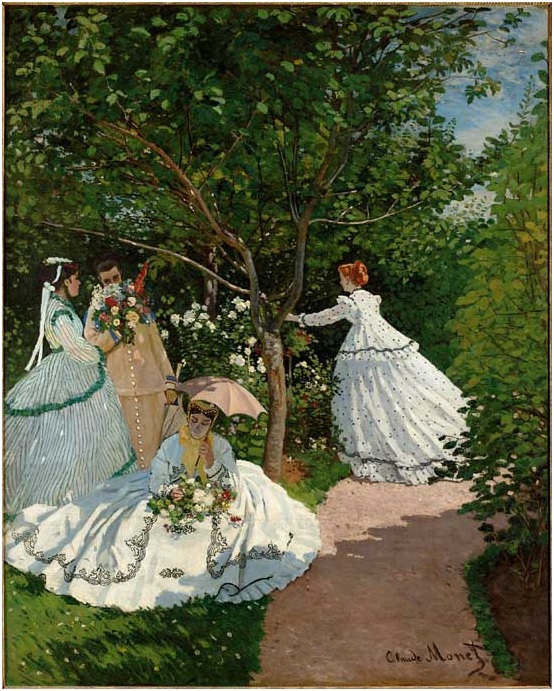

Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry. Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen.

Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen. Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color.

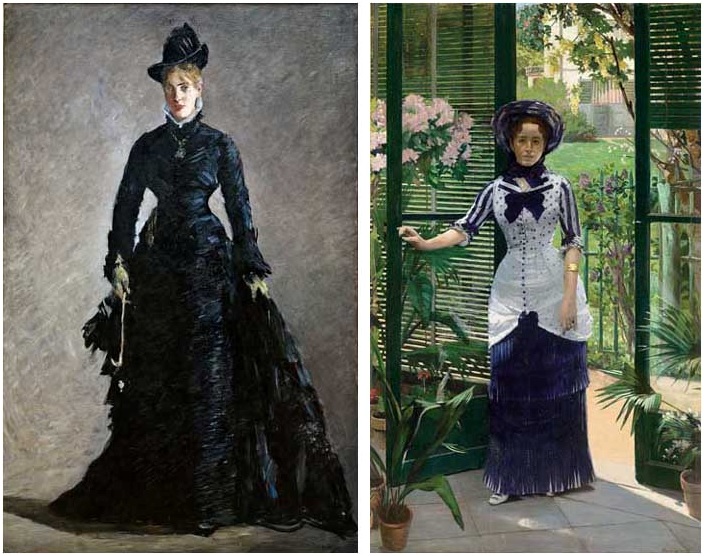

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color. Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

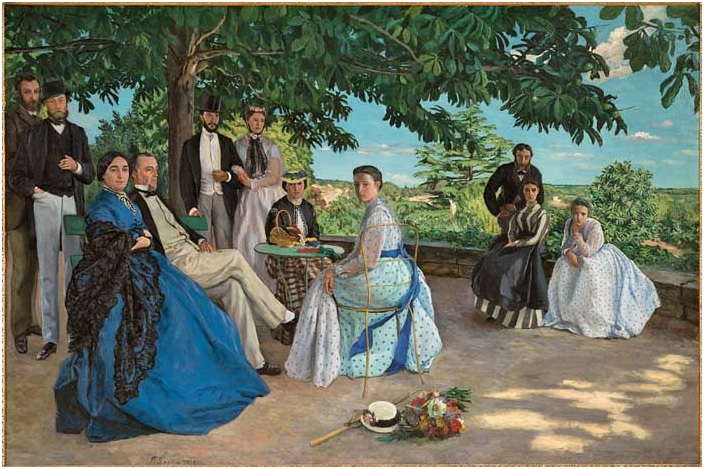

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone.

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone. Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.

Jean Dubuffet, “Site domestique (au fusil espadon) avec tete d’Inca et petit fauteuil a droite,” 1966. Vinyl on canvas, 125 x 200 cm. Fascicule XXI des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, ill. 217. Copyright Dubuffet and courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

Jean Dubuffet, “Site domestique (au fusil espadon) avec tete d’Inca et petit fauteuil a droite,” 1966. Vinyl on canvas, 125 x 200 cm. Fascicule XXI des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, ill. 217. Copyright Dubuffet and courtesy Galerie Jaeger Bucher / Jeanne-Bucher, Paris.

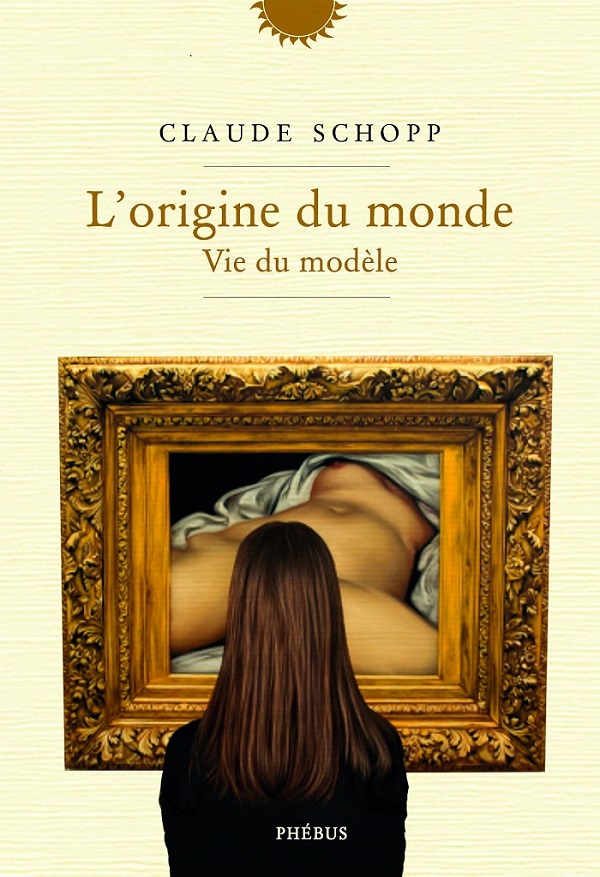

From the exhibition Sigmund Freud, From Seeing to Listening, on view at the Museum of the History and Art of Judaism through February 10: Gustave Courbet, “L’Origine du monde” (The Creation of the World), 1866. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. © Paris, musée d’Orsay.

From the exhibition Sigmund Freud, From Seeing to Listening, on view at the Museum of the History and Art of Judaism through February 10: Gustave Courbet, “L’Origine du monde” (The Creation of the World), 1866. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. © Paris, musée d’Orsay.

The Vanishing French Bench: If photography is a “Class War Weapon” — as the title of the exhibition of work by Andre Kertesz, Dora Maar, Willy Ronis and others running at the Centre Pompidou in Paris through February 4 indicates — then “Bench, Nice,” the above 1936 photo by Pierre Jamet should be plastered all over Paris and its bordering suburbs. In the past 10 years, perhaps as a measure to discourage the homeless from sleeping on them — why solve a problem when you can just make it disappear? — benches throughout Parisian area parks, streets, and Metro stations have been limned to one-person concrete chaises, (in the Metro) lines of pods interrupted by metal posts, or simply disappeared. Observing the traffic from a picturesque bridge over the Ourcq Basin this morning in the frontier suburb of Pantin, I found zero benches as far as my eyes could see on the right side, just a few on the left, and the runners outnumbered the sitters by 100 to zero. It’s a far cry from 2001, when the men sipping their first cafés (or petite blanc, white wine) of the day in the bars lining the rue Rouchechouart would regard me like a bizarre visitor from the future as I wheezed and panted up to Montmartre. Silver gelatin proof, purchased in 2011 with the support of Yves Rocher. Former collection Christian Bouqueret. Press Service, Centre Pompidou, Paris. © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GP. © Pierre Jamet. — Paul Ben-Itzak

The Vanishing French Bench: If photography is a “Class War Weapon” — as the title of the exhibition of work by Andre Kertesz, Dora Maar, Willy Ronis and others running at the Centre Pompidou in Paris through February 4 indicates — then “Bench, Nice,” the above 1936 photo by Pierre Jamet should be plastered all over Paris and its bordering suburbs. In the past 10 years, perhaps as a measure to discourage the homeless from sleeping on them — why solve a problem when you can just make it disappear? — benches throughout Parisian area parks, streets, and Metro stations have been limned to one-person concrete chaises, (in the Metro) lines of pods interrupted by metal posts, or simply disappeared. Observing the traffic from a picturesque bridge over the Ourcq Basin this morning in the frontier suburb of Pantin, I found zero benches as far as my eyes could see on the right side, just a few on the left, and the runners outnumbered the sitters by 100 to zero. It’s a far cry from 2001, when the men sipping their first cafés (or petite blanc, white wine) of the day in the bars lining the rue Rouchechouart would regard me like a bizarre visitor from the future as I wheezed and panted up to Montmartre. Silver gelatin proof, purchased in 2011 with the support of Yves Rocher. Former collection Christian Bouqueret. Press Service, Centre Pompidou, Paris. © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GP. © Pierre Jamet. — Paul Ben-Itzak