by and copyright Michel Ragon

Translation copyright Paul Ben-Itzak

From “Trompe-l’oeil,” published in 1956 by Éditions Albin Michel

Part six in the Paris Tribune’s exclusive English-language translation of Michel Ragon’s seminal 1956 novel taking on the world of abstract art, artists, art collectors, art dealers, and art critics in Paris, as well as post-War anti-Semitism in France. For the first five parts, click here. Translator Paul Ben-Itzak is looking to rent digs in Paris this Spring and for the Fall. Paul Ben-Itzak cherche un sous-loc à Paris pour le printemps. Got a tip? Tuyau? E-mail him at artsvoyager@gmail.com .

Summer had scattered the artists. The poorest remained in a Paris deserted and torrid. The better off found themselves on the Cote d’Azur, where they automatically took up the rhythm of their Parisian lives: gallery visits, squabbles between critics, internecine rivalries between dealers, interminable palaver in the cafés which supplanted le Select or le Dôme, the dazzling vista of the Mediterranean replacing the buzzing of the boulevard Montparnasse.

At the end of September, they all returned to the nest, excited by the prospect of an exhibition to prepare, an article to write, a sale practically assured. Optimism was the order of the day. Would this be the great decisive year? Everyone had the right to hope so.

Returning first, Fontenoy frequently passed by Manhès’s atelier before finally finding him at home. He was impatient to reunite with his friend; he’d saved up so many things he wanted to share with him!

He knew the majority of the habitants of the cité, a kind of housing project allocated to artists.* From the moment he entered the narrow street, a tremor of robust howling indicated that Corato was reciting the aria from “Pagliati.” Corato was one of the poorest of the abstract painters. His somewhat obscure style, extremely nuanced, attracted few fans. No dealer was interested in him. An Italian, he took advantage of the pristine tenor’s voice with which nature had bestowed him by earning his living singing operatic airs in a café-concert. But this double-life took its toll. For that matter, his tenor’s day job made it hard for his fellow painters and the critics to take him seriously. One of them had even quipped, “Corato is a professional tenor. Painting is to him like the violin is to Ingres.” Certain barbs launched for the pleasure of coming up with a witty turn of phrase can also poison the victim’s existence. This particular one really wounded Corato. When Fontenoy knocked on the door of his atelier, the tenor-painter was discomfited to see him. “You know of course that I only sing because…”

“What new paintings do you have to show me?” Fontenoy cut him off.

If he wasn’t very enthusiastic about Corato’s art, he recognized the quality of his painting, the sincerity underlying it. At times the colors revealed a contained vibration which enabled Fontenoy to get a hint of what Corato’s painting might be if it was allowed to ripen. But Corato was 50 years old. Would fatigue finish him off before he’d be able to complete his experiments and find his style?

Fontenoy carefully studied Corato’s paintings in this atelier whose walls were plastered with travel posters. He told himself that these paintings were by far superior to so many others which made a mint. How was it possible that nobody had remarked their importance? He promised himself to write about Corato for L’Artiste.

Leaving Corato’s atelier, Fontenoy hailed the aged sculptor Morini, perched on his porch in a white blouse.

After a life of misery, Morini had suddenly achieved celebrity at the age of 80. Unexpectedly very rich, he continued living in his Spartan studio, alone as he’d been all his life, altering absolute nothing in his daily routine.

“Bonjour, Monsieur Morini,” Fontenoy greeted him. “You didn’t go away on vacation?”

“Bou… bou…,” grumbled the old man. “Vacation…? I’m quite happy chez moi.”

As he seemed notably sad, Fontenoy tried to flatter him.

“It’s formidable, Monsieur Morini! Life magazine devoted three pages, in color, to you.”

“Harrumph! That would have made my poor mother happy. If she hadn’t been dead for many years now. Like all of those who would have been happy to see such an article.”

“Well,” replied Fontenoy, embarrassed, “it might have taken a while, but now that you’ve been recognized, the recognition has been hundredfold.”

The old sculptor began furiously gesticulating. He yelled: “What the hell do I care, for all their greenbacks? I can’t even eat cake. All my teeth are gone.”

This eruption brought Manhès out of his atelier.

“You’re here!”

Isabel emerged in her turn, little Moussia clinging to her dress.

Fontenoy dashed into his friend’s atelier.

“And Blanche?”

“She’s getting ready for her exhibition. We spent our vacation together on the banks of the Loire.”

“So… it’s working out then?” Manhès asked, smiling broadly.

“Yes. We get along well. She’s a quite a chic girl. There’s no reason that it shouldn’t last.”

“For me, it’s never been so good. I sold well on the Cote d’Azur and since coming back I already have enough orders to last me until the Spring. Oh, that old fart Lévy-Kahn is sure going to be sorry for his little temper-tantrum.”

“Is Ancelin back in Paris?”

“No. He’s once again let himself be shanghaied by an old widow who swept him away to New York. You know him, he never loses an opportunity to cultivate his image. Meanwhile, Mumfy’s son has enrolled in the Academy of Abstract Art. Voila a new colleague on the horizon. His old man must have calculated that it would be cheaper to have abstract tableaux fabricated by his own offspring than to keep on buying them from actual artists. I saw the family the other day, to talk to them about Blanche’s water-colors. I think she might be able to sell them a few. But Mama Mumfy told me, in plugging her son: ‘I’m not going to show you what he’s done yet. It’s not quite at a fully developed level. But he’s so sincere!’

“I responded to her with Degas’s famous quip: ‘So young, and already sincere. Madame, I’m afraid your son is already a lost cause.’ She didn’t seem very happy with this summary verdict.”

Someone knocked on the door. Isabelle went to open it. A 40ish man, elegant with slicked-back hair, entered the room and began inspecting it.

“What do you want, Monsieur Androclès?” asked Manhès, without any finesse.

“I’ve come to offer you a deal.”

“I don’t cultivate vegetables here,” Manhès exclaimed, suddenly seized with a rage that Fontenoy could not understand.

“Oh, Manhès!” shot back the man, aggrieved, “you’ll rue the day you made that bad joke.”

He departed, taking his time.

A profound silence descended on the atelier. Isabelle finally broke it.

“Perhaps you shouldn’t have snubbed him like that. You’ve just made another enemy.”

“The only ones who don’t have any enemies are the mediocrities!”

Androclès was one of the most important art dealers in Paris. He’d made his fortune during the Occupation, by selling fresh fruit and vegetables. A shrewd broker had convinced him that the most fructuous way to invest his money was to buy paintings. He’d resisted such a patently idiotic idea for a long time. But the broker found an argument with weight: “If you buy a boat,” he explained, “you’ll need to hire a crew to take care of it, and there will always be repairs that need to be made. The more you take to sea, the more it will deteriorate. Same thing for a building. You’ll need a super, a concierge. One day the roof will cave in. Then the basement will flood. A car wears down every time you drive it. Everything deteriorates, everything has personnel and maintenance costs — except painting. You can still buy a Cezanne for the price of a building. You won’t have to do anything to maintain it, and its price can only go up.”

Like Mumfy, Androclès investigated and before long he too had contracted the virus. He had the flair to acquire second-tier Impressionists at low prices and third-tier Cubists that no one wanted. Today, these Impressionists and these Cubists had finally attained their petite glory in the retrospectives and they constituted the Androclès gallery’s capital. Then this genius stumbled upon an aged Cubist painter of the variety one just doesn’t see anymore. The painter in question, simultaneously naive and sage, had been living in retirement in the country, getting by on a small income furnished by a group of loyal American collectors. During the war, he lost this clientele and plunged into such misery, such oblivion, that his wife did not survive. How on Earth Androclès, this vegetable hawker who was completely ignorant of painting, had managed to learn of his existence was a complete mystery. It’s said that even drunks have a guardian angel. It’s quite possible. But what is certain is that there must be one for philistines. This guardian angel conducted Androclès to the home of the old abandoned Cubist. He arrived with his arms loaded with vittles and departed with them loaded with canvasses. Then he bided his time. When the vegetable hawker calculated that the old man must be out of provisions, he arrived like the man from Providence with a baked ham, swept up every scrap of art which still lingered in the atelier, at 50 francs the yard, and saw himself once more hailed as a benefactor. On these raids, the old painter would scout around for a gift to offer to the dealer. He’d then give him the original edition of a book by Apollinaire which he’d illustrated in his youth, or an old drawing.

After the Liberation, the old Cubist painter died just as he was being rehabilitated. The first successful exhibition at the Androclès gallery was constituted by some of these canvasses bartered for vittles. They were bought up at fantastic prices. Today, any museum which didn’t own at least one of these masterpieces was one embarrassed museum.

Androclès no longer hawked fruits and vegetables, but his wife, a fat babushka with a vulgar voice, regaled painting collectors with her ignorance.

Fontenoy recounted to Manhès: “One day, I found myself in the gallery. A visitor asked the price of a Picasso ‘collage.’ Mama Androclès was manning the boutique. ‘Ah, that one, Mister, it’s worth the big bucks. But it’s old. Look at the paper, it’s already yellowing.'”

“You know the one,” Manhès countered, “about the guy who came to ask Androclès for Van Gogh’s address, don’t you? He didn’t bat an eye. He simply declared, in a dignified tone, ‘That gentleman is not one of my painters.'”

Moussia ran over and grasped her father’s knees. Manhès swept the child up and dangled her from his hands. The little girl giggled.

“This makes up for all of it, Fontenoy. When you have the time, you should fabricate one of these little marvels of your own with Blanche!”

Fontenoy protested: “Lay off! You used to marry me off to every single girl we met. Now that I’m with Blanche, you want us to have a kid. But what can we do? I’d tell you that an artist isn’t made to have kids, but it would only piss you off.”

“What, you don’t like our little Moussia?”

“Sure I do, she’s a darling. But just because I like something I see chez les autres doesn’t mean I want to have it chez moi.

“Ah! And now,” announced Manhès in affectionately nudging the tot away, “now go play. Papa needs to work….(and he added, emphatically) I tell you, Fontenoy, between the wife and the kid…!”

*Originally applied to housing complexes constructed for workers, today the term ‘cité’ most often refers to housing projects in the poorer neighborhoods or border suburbs of French cities. Before the expansion of the Montparnasse train station in the 1950s which leveled them, the 13th, 14th, and 15th arrondissements of Paris housed many of the cités reserved for artists. (When the translator lived in the Cité Falguière in the 15th in 2000, the former atelier of Chaim Soutine was still visible at the entrance.) Michel Ragon notably wrote about a visit to the sculptor Brancusi’s atelier before it in turn was re-located, intact, to another part of the city… to make way for progress. (Translator’s note.)

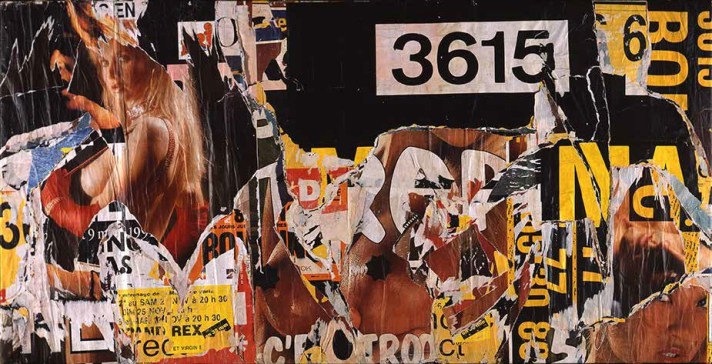

It’s fitting that Jacques Villeglé — like the pioneer in the art of the lacerated street poster (and the modern French detective novel) Léo Malet in the 1930s, an inveterate street-walker — realized his final work in removing and re-constituting the posters for erotic “message boxes” on the Mintel (the French ancestor of the Internet) that began plastering the rues of Paris between 1989 and 1992, when posters became largely supplanted by billboards. “There’s a certain affinity between the artist and these modern Lorettes,” Harry Bellet writes for the catalog of the works’ exhibition, running through April 12 at the gallery Vallois in Paris. “Like (the subjects of the posters), he walked the streets…. He also has an admirable respect for them: They display themselves — or rather they’re plastered up. He unglues them, liberates them…. Sometimes he tears them up, certainly, but as he confided to Nicolas Bourriaud…, ‘A wounded visage is still beautiful.’ In fact, Villeglé hasn’t lacerated these women; he’s softly, tenderly, langorously but always lovingly blown the leaves away.” Above: Jacques Villeglé, “Route de Vaugirard, Bas-Meudon, April 1991,” 1991. Lacerated poster mounted on canvas, 152 x 300 cm. Copyright Jacques Villeglé and courtesy Galerie Vallois.

It’s fitting that Jacques Villeglé — like the pioneer in the art of the lacerated street poster (and the modern French detective novel) Léo Malet in the 1930s, an inveterate street-walker — realized his final work in removing and re-constituting the posters for erotic “message boxes” on the Mintel (the French ancestor of the Internet) that began plastering the rues of Paris between 1989 and 1992, when posters became largely supplanted by billboards. “There’s a certain affinity between the artist and these modern Lorettes,” Harry Bellet writes for the catalog of the works’ exhibition, running through April 12 at the gallery Vallois in Paris. “Like (the subjects of the posters), he walked the streets…. He also has an admirable respect for them: They display themselves — or rather they’re plastered up. He unglues them, liberates them…. Sometimes he tears them up, certainly, but as he confided to Nicolas Bourriaud…, ‘A wounded visage is still beautiful.’ In fact, Villeglé hasn’t lacerated these women; he’s softly, tenderly, langorously but always lovingly blown the leaves away.” Above: Jacques Villeglé, “Route de Vaugirard, Bas-Meudon, April 1991,” 1991. Lacerated poster mounted on canvas, 152 x 300 cm. Copyright Jacques Villeglé and courtesy Galerie Vallois. From the Arts Voyager archives: Paul Klee, Untitled, 1939. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

From the Arts Voyager archives: Paul Klee, Untitled, 1939. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

I’ve often wondered: If an alien looked down on us, what would he see? At this moment on the streets of Paris, an awful lot of people talking into little boxes or who simply seem to be talking to themselves, ignoring their prochaine to pummel their box with their fingers. Until the aliens arrive, we can count on artists to give us a clairvoyant perspective on this society increasingly depourvu de la contacte humaine. So if you can get away from your little box and lift your eyes long enough to negotiate the narrow labyrinthine rues of the Marais, the above oeuvre by Catherine Balet, “Moods in a Room #34 (2019),” as well as other works by the hybrid artist pastiching painting and photography to investigate contemporary mores, is on view through March 30 at the Galerie Thierry Bigaignon at 9 rue Charlot. (Chaplin — or Charlot as the French call him — no doubt someone else who might have had something to say about the zombies walking the streets with their heads in the cyber-sand.) Courtesy Galerie Thierry Bigaignon. — Paul Ben-Itzak

I’ve often wondered: If an alien looked down on us, what would he see? At this moment on the streets of Paris, an awful lot of people talking into little boxes or who simply seem to be talking to themselves, ignoring their prochaine to pummel their box with their fingers. Until the aliens arrive, we can count on artists to give us a clairvoyant perspective on this society increasingly depourvu de la contacte humaine. So if you can get away from your little box and lift your eyes long enough to negotiate the narrow labyrinthine rues of the Marais, the above oeuvre by Catherine Balet, “Moods in a Room #34 (2019),” as well as other works by the hybrid artist pastiching painting and photography to investigate contemporary mores, is on view through March 30 at the Galerie Thierry Bigaignon at 9 rue Charlot. (Chaplin — or Charlot as the French call him — no doubt someone else who might have had something to say about the zombies walking the streets with their heads in the cyber-sand.) Courtesy Galerie Thierry Bigaignon. — Paul Ben-Itzak

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection.

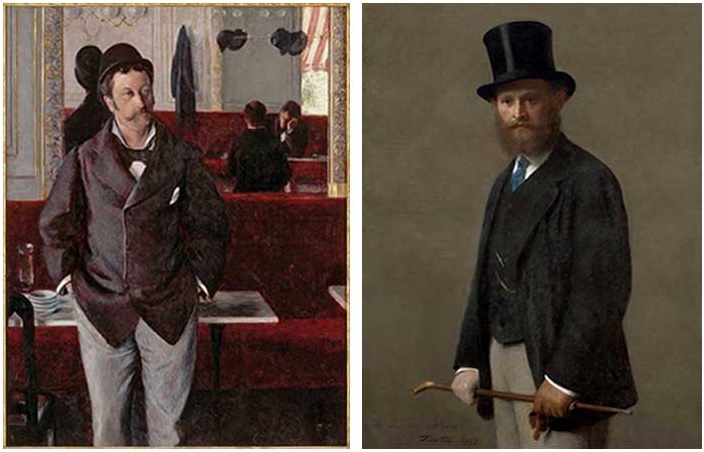

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection. Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.)

Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.) Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart.

Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart. Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry.

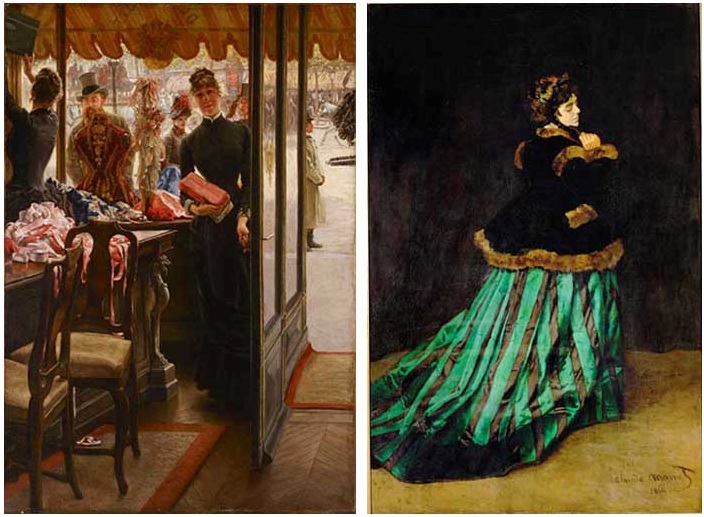

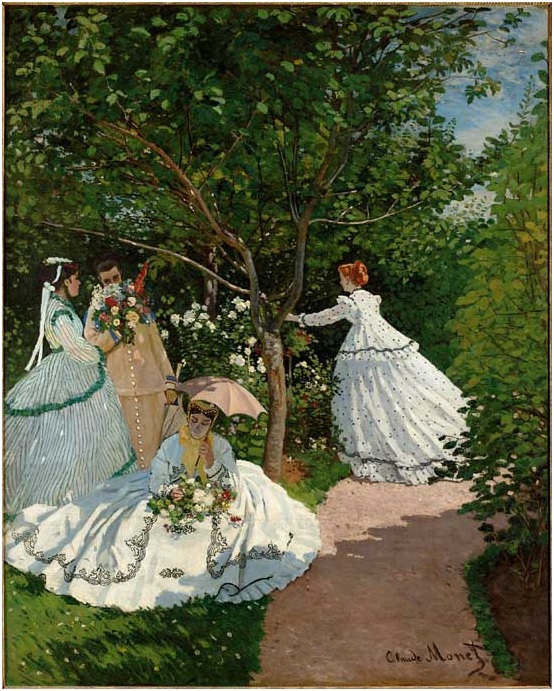

Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry. Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen.

Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen. Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color.

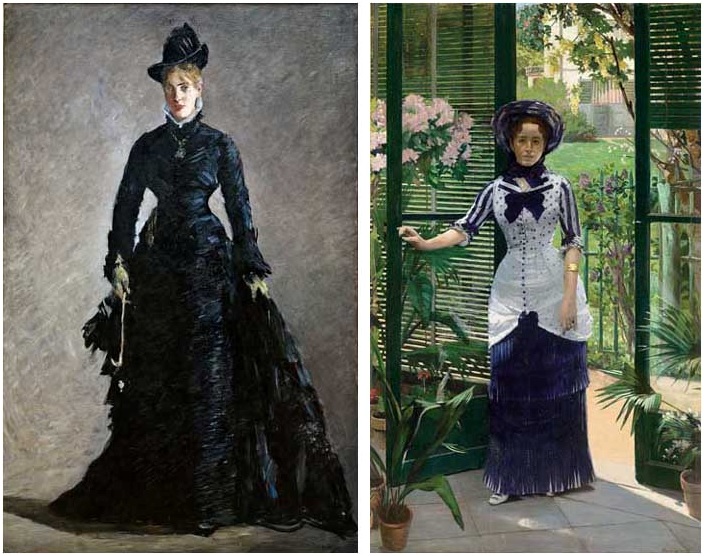

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color. Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

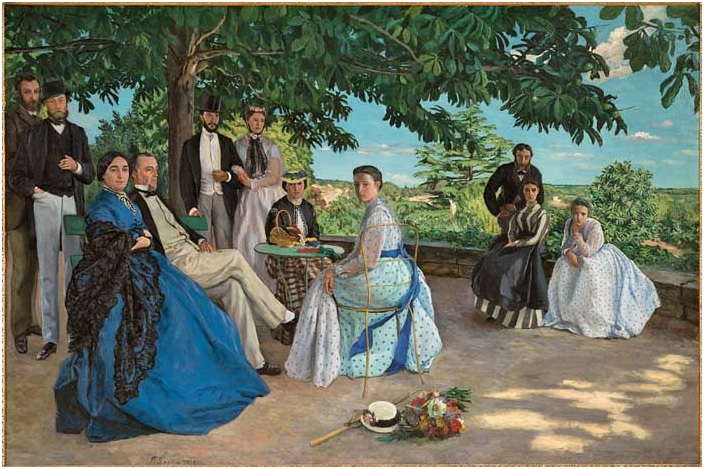

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone.

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone. Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.