First sent out by e-mail, and posted today for the first time. After getting more than half-way through with a re-edit seven months later, I’ve decided to leave this piece in its initial, raw, somewhat over-detailed initial state for the sake of authenticity… and for the record. — PB-I, October 23, 2019

PARIS — So there I was at dusk, heart broken and gums bleeding, teeth throbbing, staggering up the rue des Martyrs towards the Montmartre cemetery and the grave of the man I blamed it all on: Francois Truffaut.

In the late French director’s five-film, 20-year saga that began with the 1959 “The 400 Blows” and climaxed with “Love on the Run,” Antoine Doinel, played throughout the cycle by Truffaut’s alter-ego Jean-Pierre Leaud, is always on the run, often from the women in his life: His mother, his wife (the effervescent Claude Jade, whom Antoine, in the 1968 “Stolen Kisses,” rightly calls “Peggy Proper” for her prim manners), his girlfriend (Dorothee, who made her debut in “Love on the Run” and would go on to become the French equivalent of Romper Room’s Miss Nancy), his older married mistress (Delphine Seyrig at her glamorous apex), and various intermittent mistresses. The only one he seems to chase, apart from Dorthee’s “Sabine,” whom he loves but whose love seems to scare him (he found her after patching up and tracing a photo of the girl a supposed lover had torn up in a restaurant basement phone booth during an angry break-up call he overheard), is Marie-France Pisier’s “Colette,” who we first meet in Truffaut’s 30-minute contribution to the 1963 multi-director film “Love at 20.” (They encounter each other at a classical music concert; Antoine is working at the time in a Phillips record factory, with Truffaut letting us see the hot wax being spun into discs. In “Love on the Run,” Antoine finally tracks Dorothee’s Sabine to her work-place. A record shop where couples make-out in listening rooms.) You may remember Pisier as the vengeful sexpot in the movie adaptation of Sidney Sheldon’s “The Other Side of Midnight,” in which she introduces an inventive way of hardening an older man’s penis which might have come in handy in my own recent saga if I’d only have remembered it before now.

The first hint that I was starring in a sort of Bizarro universe re-make of, specifically, “Love on the Run” came when the woman in question — you know her as “Vanessa,” whom I described picking up on (although I’ve since learned that she may have been picking up on me) at a vernissage a few blocks from the Pere Lachaise cemetery (cemeteries also figure in the Antoine Doinel cycle; the Montmartre one where Truffaut was eventually buried turns up in three of the five films, notably as the burial place of Antoine’s mother, revealed to him by her former lover as being next to the real tomb of the model for “Camille.”) and right after having three teeth extracted, e-mailed me from the Lyon train station before boarding a train to that city to visit her grandkids (like Antoine, I seem to have unresolved mother issues) to tell me that the night, our first together which had concluded the previous morning, and which we’d both exuded at the time was extraordinary and unique (she’d e-mailed me afterwards that she didn’t understand why we weren’t still together) felt “incomplete” (later she’d call it “inaccomplished”) because I couldn’t or wouldn’t get it up. (My wording; she didn’t put it so vulgarly.) In the Truffaut film, after Colette calls him from a window on a Lyon-bound train at the Gare de Lyon, where Antoine has just dropped of his son for camp, Antoine jumps on the moving train without a ticket, surprises Colette in her sleeper car right after a fat middle-aged businessman, assuming she’s a prostitute, has rubbed up against her in the aisle (a lawyer, she’d spotted Antoine earlier in the day at the court-house, where with Jade he’d just completed France’s first no-fault divorce, an echo of my parents’ some years earlier). After they catch up, she upbraids him on the revisionist way he recounted their courtship as 20-year-olds in a fictionalized memoir he’s just published — “My family didn’t move in across the street from you, you followed us!” (At the time, Antoine is working as a proofreader at a – literally – underground publisher on a book detailing the 18 minutes when De Gaulle disappeared during the 1968 student-worker uprising. Letters requesting love assignations sent by underground pneumatics also figure in the 1968 “Stolen Kisses,” in this case from Antoine’s older, married lover – his employer’s wife — played by the glamorous Seyrig.) He tries to kiss her, she light-heartedly repels the attempt scolding him, “Antoine, you haven’t changed.” The conductor comes around for tickets, Antoine pulls the emergency chord and jumps off the still moving train. We see the now 34-year-old Antoine running across a field, an echo of the last, poignant, liberating moment in “The 400 Blows,” when a 14-year-old Antoine, having escaped from a youth home/prison, is frozen on screen and in our memories, a broad smile on his face as he runs on a beach, discovering the ocean (the antipathe of Chris Marker’s ocean in “La jete”) for the first time.

In my own Bizarro universe re-make of the Antoine-Colette train scene, it was Colette who, after having joined me in a mutually agreed upon and extraordinary kiss was jumping from our train.

I was devastated, as I thought we’d also both agreed that what made our first night together magical is that the things other couples often view as preliminary — hand-holding, snuggling, French kissing, hand-kissing — had for us been electric. (I’m purposely avoiding citing the many words and motions we exchanged which confirm this because this piece is not intended as an indictment – “If you don’t love me, what was this?”) After writing her an e-mail to ask why she chose to bring this up in an e-mail as opposed to face to face, and explaining that if you want your partner to get it up, the worse thing you can possibly do is tell him it bothers you that he couldn’t get it up, and that a 57-year-old man can’t just get hard on command, I said she should ask herself, “If he was impotent, would I continue with him?” and if the answer was no, get out. She misinterpreted this in a more dire manner, we made up Friday, but only for her to send me another e-mail Saturday — 20 minutes before she knew I was receiving guests, my artist friends K. & R. for the famous Palestinian and Jamaican chicken twins, breaking up. And adding if I wouldn’t mind returning the scarlet scarf her Islamophobic friend had left at my home after I asked her and her husband to leave a dinner part I’d hosted for them all when they started going at French Muslims. So it was with misty eyes that I opened the door to K. & R., and found myself confiding my troubles of the heart with friends with whom I’d not yet reached that level of intimacy. Thanks to their and particularly K.’s good humor — leading the conversation to other subjects but ready to go back to consoling me, even suggesting, “We need to find you a woman!” — I did pretty well, considering a germinating girlfriend had just broken up with me by e-mail. But I guess I must have sounded worse than I felt, because when I asked what I should do if she contacted me again, K. said “Drop it! Do you want to end up jumping out a window?!”

After more e-mail exchanges last week, the tenor of which from Vanessa remained mostly consistent — she was still running from the love express our train had become — I finally ceded, agreeing it was better to cut it off as I couldn’t return to the just-friends thing, she sent me an e-mail where she said that she too (as I’d expressed I was) was in tears, that her life had changed since “1/24” — the evening we met at the vernissage — that she’d never be the same again, that she knew she had a problem with loving, that she hoped I’d find someone but that it was probably too late for us.

This of course — the tears — brought me running, and I wrote her to say that I’d been blind, that she maybe thought she had a problem with love but that everything she’d done in my regard — particularly being ready to lose me — was done out of love.

On Friday we had another magical evening, organizing an impromptu, wintry pique-nique on the banks of the Ourcq canal. I assured her I wouldn’t go all out but just bring what was already in the house; as it happened this also included a vintage wooden unfoldable pique-nique table in a valise that came with the apartment. I’d promised her to go no further than a chaste kiss goodnight at the Metro station. “Vanessa and Paul, round two!” she’d blithely announced over the hummus, and the rest of the evening kept to this light tenor, with lots of laughter. At one point I stopped the converation to note: “This is important. You see? When we’re face to face, we understand each other. E-mail communication is really sinister.” The night concluded with a chaste kiss at the Metro.

Ghosts in the machine

Wanting to diversify my world — I’d be making my famous Palestinian chicken for friends of Vanessa and bringing it to the house they were moving to that day, looking out over (I’m not making this up) the Pere Lachaise cemetery — on Saturday morning I decided to check out the vernissage for a group exhibition in my suburban Paris village of the pre Saint-Gervais. Life is more than women! Life is more than the women in my life over the past few years who seem to be Bizarro Universe interpreting the scripts for Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel films!

After sensing that in lieu of the usual joy of discovery I still feel around art I was feeling incredibly wary after entering the art space, in the same room below the covered market where I’d scored my old aborted professor Jerome Charyn’s “The Catfish Man” — I was increasingly regretting that I lacked the coping skills Charyn’s hero (himself) had been inculpated with by being forced to tangle with the urban catfish in the mudflats of the Bronx of his come-uppance — when someone I didn’t recognize at first, a woman in her ’50s with a boyish hair-cut, rose up like one of Charyn’s catfish and announced in wonder, “Paul.” It was another V, the last girlfriend and who, in contrast to the current V., who never stopped blaming herself for being unable to love, had taken the opposite tactic with me when we last tango’d/tangle’d nearly three years ago, blaming it all on me, even though in this case the opposite was true; this was one sick puppy. I know this sounds like the usual break-up sour grapes, but I’m short-handing because she doesn’t merit more time than this. I simply mention the encounter because it may have been an omen….

… And to introduce what I conveyed to “Vanessa” as we marched from the ill-advisedly chosen Pere Lachaise rdv to the dinner at the home overlooking the cemetery. I know it’s not advised to mention an ex to a current, but for me this was a means of delivering a series of compliments:

“Where she doesn’t assume any responsibility, you unfairly blame everything on yourself…. And even though she’s 14 years younger than you, on looks there’s no contest.” Vanessa smiled widely at this. “She’s skinny-ass where you have the body of a woman, uninteresting to look at where you are.”

I was annoyed when …. No, I find I can’t go into what annoyed me, nor any other details of the party related to my interactions with “Vanessa” because it sounds like evidence gathering, and this piece is not intended to be an indictment nor a reckoning, but a first step on the path out — out of heartbreak and out of “Vanessa” — for myself. I also believe that, like an American black-belt I once knew in Antwerp once explained to me in saying why the very fact that his hands are deadly weapons means he has a reponsibility *not* to fight, a writer doesn’t have the right to use his considerable gifts in romantic reckoning.

So suffice to say that the evening seemed to end sublimely, with Vanessa and I getting lost in perpetual circling of a Paris roundabout, this one the Place Gambetta. We held hands from the moment we left the hosue; there was some warm French kissing. When I said I wanted her to come home with me, she responded that she “wasn’t against” this, but reminded me that she had to get up early to go meet her grand-daughter at the train station.

We seemed to part in joy hands taking an extra clutch before separating…

…but..not before, unprompted, she asked out loud again why she was unable to jump into my arms, then answered her own question with “Is it because you couldn’t get it up?,” though not putting it that way, again sorting the demon.

Once home, in a letter I sent on getting home at 1:30 a.m., I felt compelled to repeat my earlier answers, both the defensive and proactive ones: If you want a man to get it up, the worse thing you can do is tell him it bothers you when he can’t; and then detailing, explicitly, all the other ways I’d like to please her, and ending with, “Let’s have fun with it!”

In the last e-mail I sent her Sunday before she let the hatchet fall again (and once again by e-mail), I wrote, rather poetically (she completed the beauty and humor before lowering the ax), regarding our lost midnight turnabout, “I’d rather be lost with you than found with anyone else.”

Oh and I left out one important detail: After one embrace, I finally said the words in person for the first time: “Je t’aime,” with a big smile on my face. “What am I supposed to say?” “You’re not supposed to say anything, just accept it.”

I mention this because since she broke with me after the late Saturday night letters, I’ve been torturing myself with: Did the letters, particularly the lasciciousness, scare her away? What if I’d backed off – after the happy Metro separating – and allowed her the space to come to me. So to counter this self-torturing (I even mentioned this possiblity in my last letter to her – if I’d backed off, I might not have lost you) I’m trying to tell myself that it was more this first face-to-face declaration of love that did it.

Ultimately I think this is the problem, the reason that Sunday and Monday morning she pulled out, saying she was arresting the histoire d’amour with me because she wasn’t “at the hauteur” of my emotions and compliments to her, to a degree that it was making her sick: I don’t think she has a problem with loving (at one point she told me she’s never been able to love, that she ended her two marriages because of this); I saw this manifest from her towards me in copious ways over the past two plus weeks. I think she has a problem with accepting being loved.

Before starting this piece this overcast Tuesday morning, I’d determined not to read any new mails from V. because I knew if I read them I’d have to respond. (And that I shouldn’t have given her the power to confirm or deny that my letters, sentimental and lascivious, of late Satruday had scared her off.) The one I did receive from her this morning, sent last night, confirmed this urge but so far I’m resisting. Not so much because I’ve convinced myself that it’s unhealthy to continue on her roller coaster (I’ve left out the numerous things she’s said or acts she’s done which indicate a profound love because this is not intended to be a requisatory, but a first step towards my own healing .. and advancement / continuation in the search for the vrais amour) but because I’ve told the part of myself unable yet to fall out of love with her, unable to let go even though my brain and a large part of my heart realizes that this is unhealthy, to let myself be swallowed up by a heart that is really broken, that this is my last hope, I’ve decided to follow two precious pieces of advice dispensed to me by my New Zealand-bred horse chief on a pony farm along the Texas – Oklahoma border more than six years ago:

- You can’t blame yourself for the things you can’t predict. All signs — all the signals she sent me — indicated that this woman was crazy about me from the moment she encountered me. I but responded to that with the joy in my heart this provoked.

- If you want a horse/filly to do what you want, the worse thing you can do is keep barking at him. You need to give him/her time to digest what you just said, so that he ultimately makes the decision him/herself.

I don’t know if she’ll write me again. I don’t know if I’ll be able to keep from opening any mails she might send, or from responding if I do. But this is what I’m going to attempt, at least for a week. What I do know in my heart of hearts is that she’s hurt me so much with the ups and downs that it will take more than an e-mail to convince me of any change of heart that she might have, or rather return to the previous obsession she announced with me. I need her to do what she’d refer to as a “Woddy Allen,” running to me breathlessly along Fifth Avenue Woody at the end of “Manhattan,” arriving panting and breathless at my door before I move on.

But to get back to the French director towards whose whose grave I found myself staggering up the rue des Martyrs as the sun set over the Sacre Coeur church which slowly emerged above it, gums bleeding from the just-extracted tooth, heart still raw. Once at the grave, after filling my green plastic up from a nearby fountain with water and popping a dissolvable 1000 gram Paracetemol into the water, posing it on Truffaut’s grave (decorated with an unravelling 35 MM film spool and a worn photo of Truffaut, Leaud, and a woman who might have been Claude Jade on the set)and watching it fizz away like this love affair, I lifted the glass and, echoing the Charles Trenet song which provides the theme for the 1968 “Stolen Kisses” – in which Leaud’s Antoine and Jade’s Christine fall in love – toasted Francoise Truffaut with “A nos amours,” to our loves. I might have added “This is all your fault,” for setting a model of Antoines and his women I was continuingly trying to counter-act. I wanted to be the anti-Antoine, proposing a definite “OUI!” to all these French women I was encountering. Why did they keep behaving like Truffaut’s Antoine, falling in love only to deny it and jump off the train, fleeing into the great French wilderness, fleeing love – mine and theirs – on the run?

From the Arts Voyager archives: Paul Klee, Untitled, 1939. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

From the Arts Voyager archives: Paul Klee, Untitled, 1939. Image copyright and courtesy Artcurial.

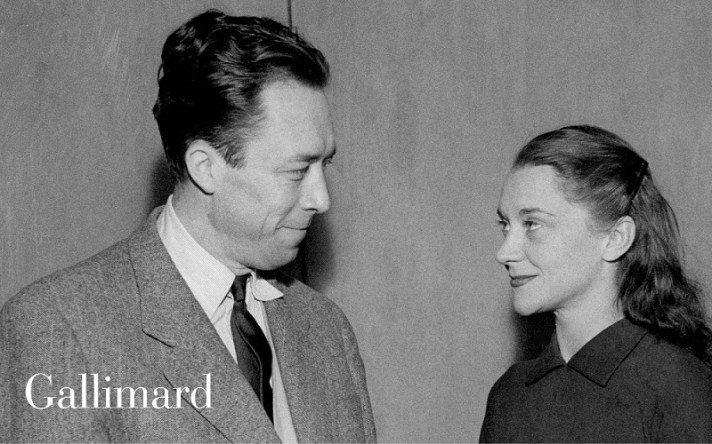

Albert Camus and Maria Casarès. Book cover photo courtesy Gallimard.

Albert Camus and Maria Casarès. Book cover photo courtesy Gallimard.

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection.

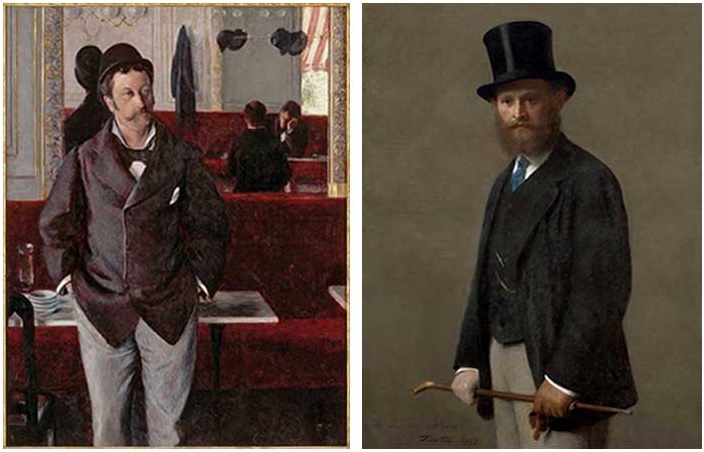

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” 1877. Oil on canvas, 83 1/2 x 108 3/4 in. (212.2 x 276.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection. Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.)

Left: Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894), “At the Café,” 1880. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 44 15/16 in. (153 x 114 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. On deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Right: Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836-1904), “Edouard Manet,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 46 5/16 x 35 7/16 in. (117.5 x 90 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund. Forget the fashion plate, Caillebotte here seems primarily concerned with light and reflection — from the street, from the mirror, subdued by the awning in the street — and with seeing how much he can do with red. (Caillebotte was not only an artist, but a collector. It may be hard to fathom in these days of competing Impressionism exhibitions, but his bequest of 70 Impressionist masterworks to the French nation when he died in 1894 was greeted with outrage by many of the old guard. Old guard chef Gerome proclaimed that “for the Nation to accept such filth, there must be a great moral decline,” calling the Impressionists “madmen and anarchists” who “painted with the excrement” like inmates at an asylum. The bequest was refused three times, with the result that French museums ultimately lost some of the work. (Sources: Michael Findlay, “The Value of Art,” Prestel Verlag, Munich – London – New York, 2012, and Henri Perruchot, “Cezanne,” World Publishing Company, Cleveland, New York, Perpetua Ltd.,1961, and Librairie Hachette, 1958.) Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart.

Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Lady with Fans (Portrait of Nina de Callias),” 1873. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 65 9/16 in. (113 x 166.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest of M. and Mme Ernest Rouart. Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry.

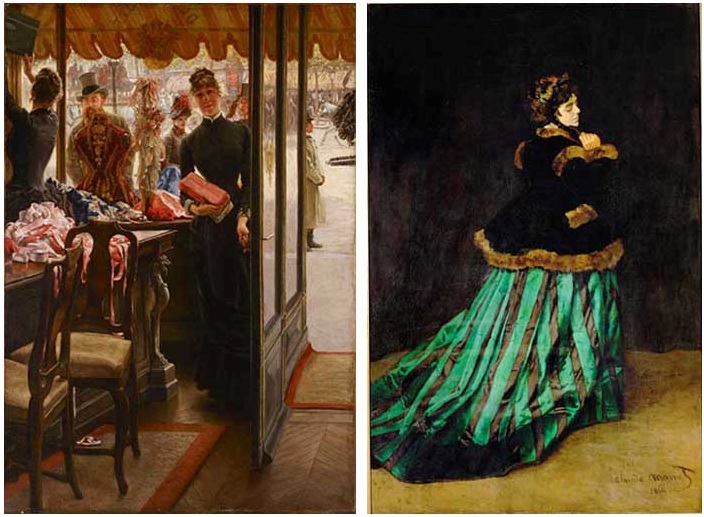

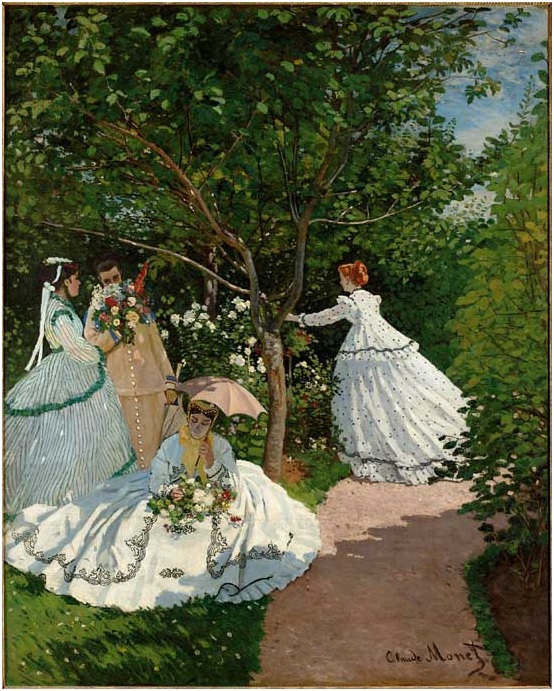

Left: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), “Portraits at the Stock Exchange,” 1878-79. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 1/4 in. (100 x 82 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Bequest subject to usufruct of Ernest May, 1923. Right: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “Repose,” ca. 1871. Oil on canvas, 59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in. (148 x 113 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry. Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen.

Left: James Tissot (French, 1836-1902), “The Shop Girl from the series ‘Women of Paris,'” 1883-85. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 40 in. (146.1 x 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from Corporations’ Subscription Fund, 1968. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Camille,” 1866. Oil on canvas, 90 15/16 x 59 1/2 in. (231 x 151 cm). Kunsthalle Bremen, Der Kunstverein in Bremen. Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color.

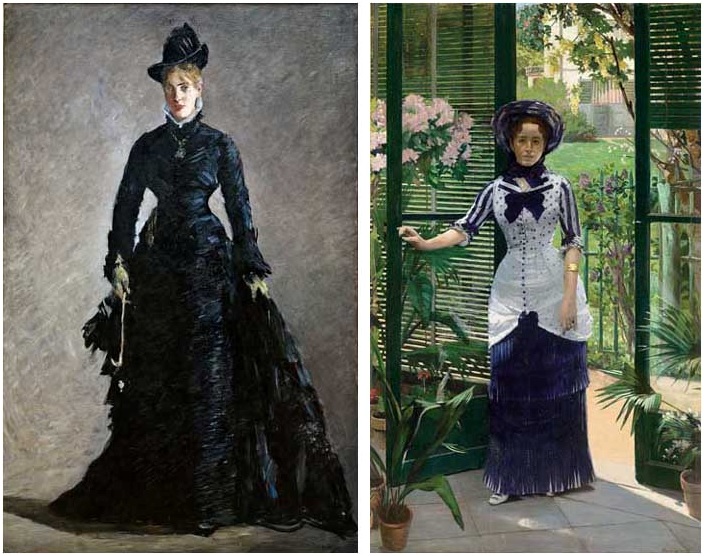

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841-1895), “The Sisters,” 1869. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 32 in. (52.1 x 81.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. Gift of Mrs. Charles S. Carstairs. Contemporary and early 20th-century critics often unfairly thumb-nailed Morisot as a ‘women’s painter,’ blinded as they were by her feminine (read: ‘gentle’) subjects (the word most often used to describe her oeuvre was douce) from seeing the hard technical problems she was trying to solve, frequently involving employing a simple spectrum to achieve a complex result, often involving multiple planes. Here the challenge she’s set herself seems to be creating three dimensions out of one predominant color. Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), “The Parisienne,” ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, 75 5/8 x 49 1/4 in. (192 x 125 cm). Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Bequest 1917 of Bank Director S. Hult, Managing Director Kristoffer Hult, Director Ernest Thiel, Director Arthur Thiel, Director Casper Tamm. Right: Albert Bartholomé (French, 1848-1928), “In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé),” ca. 1881. Oil on canvas, 91 3/4 x 56 1/8 in. (233 x 142.5 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée d’Orsay, 1990.

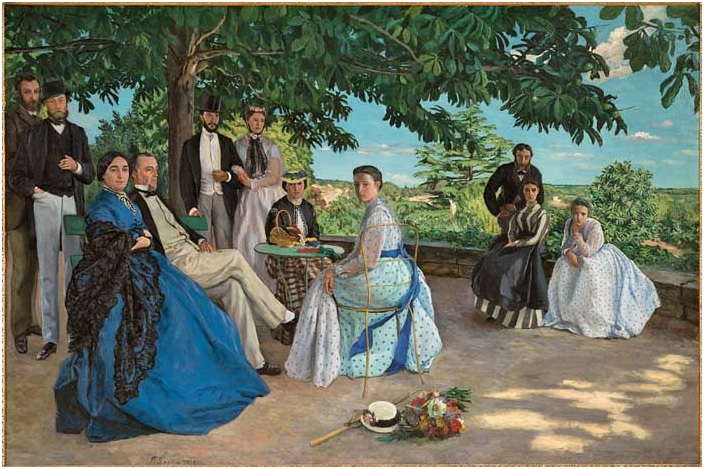

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone.

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), “Family Reunion,” 1867. Oil on canvas, 58 7/8 x 90 9/16 in. (152 x 230 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired with the participation of Marc Bazille, brother of the artist, 1905. While the older Pissarro fled to London as the Prussians approached the Paris suburbs (at a high tarif; they requisitioned his home as a slaughterhouse and did their bloody chores on some 1,500 of his works), Bazille stayed to fight and paid with his life, giving this piece a poignant undertone. Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (left panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 164 5/8 x 59 in. (418 x 150 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of Georges Wildenstein, 1957. Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), “Luncheon on the Grass (central panel),” 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 97 7/8 x 85 7/8 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Acquired as a payment in kind, 1987. From the exhibition Sigmund Freud, From Seeing to Listening, on view at the Museum of the History and Art of Judaism through February 10: Gustave Courbet, “L’Origine du monde” (The Creation of the World), 1866. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. © Paris, musée d’Orsay.

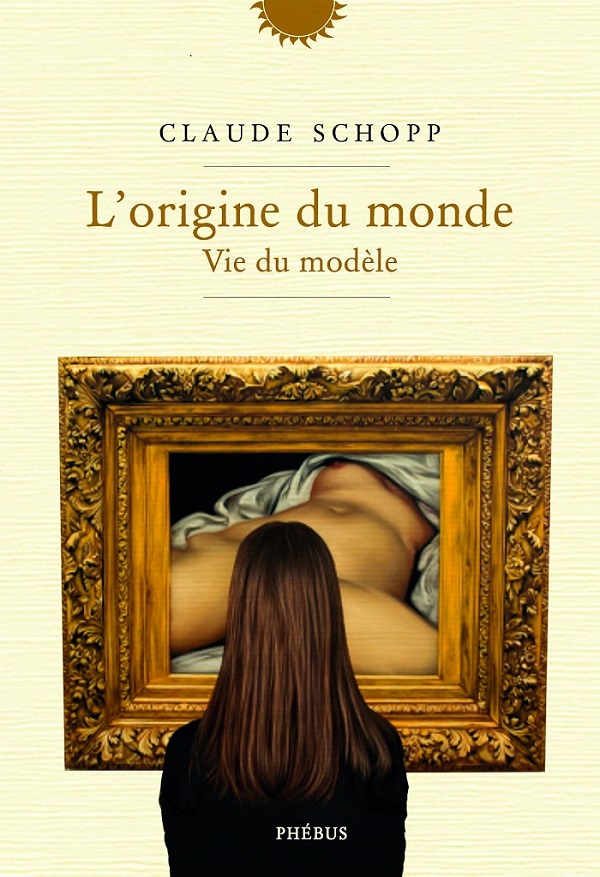

From the exhibition Sigmund Freud, From Seeing to Listening, on view at the Museum of the History and Art of Judaism through February 10: Gustave Courbet, “L’Origine du monde” (The Creation of the World), 1866. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. © Paris, musée d’Orsay.